Patuxent Riverkeeper Fred Tutman talks race and the environment | Part 1 of 3

By: Malaika Elias

This month, Waterkeeper Alliance is focused on telling stories about intersectional environmentalism. In this 3-part series, Waterkeeper Alliance Organizer Malaika Elias sat down with Patuxent Riverkeeper Fred Tutman to discuss race and the environment, Environmental Justice, and the Patuxent River. Read more below.

Malaika Elias: Who are you? Tell us a bit more about yourself and involvement with Patuxent Riverkeeper.

Fred Tutman: My name is Fred Tutman and I’ve been the Patuxent Riverkeeper for the past 14 years. We started in 2004, but I’ve been an activist on this river for 30 + years. The river has been a symbol and a spiritual feature of my upbringing and life in southern, rural Maryland. My family grew tobacco and watered their crops from this river. My great-grandfather fished for yellow perch in this river. I swam in this river as a boy. In every respect, as much as I’ve lived in other places and enjoyed other rivers, the Patuxent is very much my home river.

The Patuxent was the first river in Maryland’s history to use the Clean Water Act to force the state to clean it up. And it’s the Patuxent River that’s responsible for the movement to protect the Chesapeake Bay. Three federal lawsuits were won in the 1960s and 70s on the Patuxent that resulted in its cleanup. When an attempt was made to memorialize those lawsuits in a remedy plan, the state found they didn’t have enough political districts on the river to get State legislation passed so the governor started the State’s Chesapeake Bay Program. So the little-known truth is that the only reason people are fighting to save the Bay is because of the Patuxent River. Patuxent Riverkeeper stepped up and started the charge. Others lit the fuse, but I think it’s our job at Patuxent Riverkeeper to keep that fuse lit. Not because we are pugnacious, but because we passionately believe in the power of one and the power of many all at the same time. We fight to activate communities and empower people to defend their water and I think that’s huge. It doesn’t have to be staffed out and it doesn’t take a lot of material. It’s all about having the spine to stand up for what’s right and fight.

ME: You’ve spent a lot of your time engaging communities of color and Environmental Justice communities. What does Environmental Justice mean to you? And how are you engaging and empowering those communities?

FT: Environmental Justice to me is entirely about fighting injustice and inequality. When you say the words “Environmental Justice,” most people think you are talking about black folks or people of color. We see it in a much more pure sense. These are David and Goliath fights where people with far less power are largely fighting people with an exorbitant amount of power and money. And that can be a white, black or Asian community; any community except a rich community. You don’t find many rich communities fighting off coal-fired power plants or CAFOs or sewage discharges; those, frankly, are placed where there is less money and less power and the two seem to go together. So I would say we at Patuxent Riverkeeper are part of a social activist movement where the environment is key in our lense. We are community organizers where our sense of community is defined by the track of the river.

The Patuxent is an extraordinary river that has a lot of punch as far as defining what Maryland’s obligations are to protect its water. But I think the Patuxent’s best stories come out of the connection between people and these waterways. We try to identify and honor those connections as best we can. We frequently have Native Americans, African Americans, white people, and people of every walk telling us their stories and engaged in our Patuxent movement.

One way we bring power to these communities is through expertise. We bring legal expertise, we bring water-based knowledge, and we bring context. So for example, when we first approached and began working with Eagle Harbor (a small Environmental Justice community on the Patuxent), they told me they wanted solar panels. I called the people I know that are familiar with solar panels. Now we’re trying to put a deal together for the town and I think that’s instrumental because we are responding to what the community’s vision is. We didn’t tell them to get solar. They told us they wanted to learn more and enlist our help in finding available options. Our conversations with towns like Eagle Harbor almost always start with us trying to glean what their needs are. We sit with them at town and community meetings, listen to what they are talking about, and wait for an opportunity to be of service.

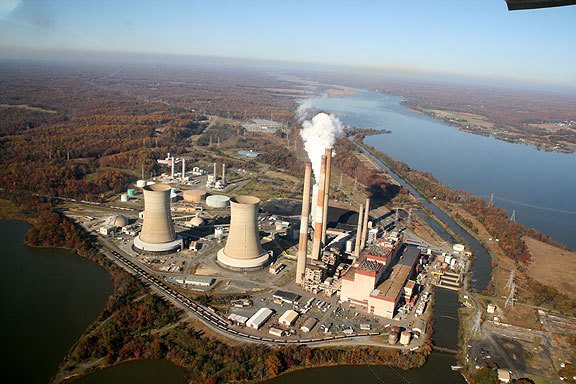

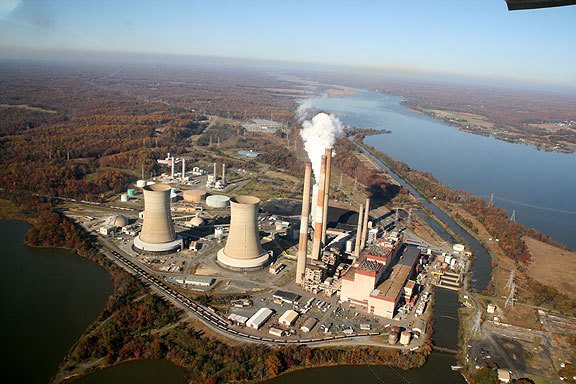

It is key that this particular town has been steeped in a legacy of racism and injustice since its founding. When beaches in the area were restricted for people of color, Eagle Harbor was formed as a black enclave and resort in the 1920’s. Part of the town is a former steamboat landing site that once transshipped slaves who worked the Maryland Tobacco fields in the 1800’s. Like many places in our watershed, the context for what exists there now was shaped by the legacy of past and present disparities and injustices of various sorts. The adjacent neighbor is a massive coal-burning power plant (Chalk Point) that has had numerous unlawful discharges and violations that affect the town. Just acknowledging that past context and present reality helps us connect and serve this town. It is a beautiful town with a beautiful story to tell.

When we are able to be of service, communities reciprocate. They support us in return. In the end, it’s all about them, and we connect them to each other sometimes. In the case of Eagle Harbor, we connected them to another black town, Highland Beach, who exchanged helpful information on how they had gotten solar panels and a sustainable communities designation. The town is following by example. In a sense, we are building a far-flung sense of community around water and environment. We’re helping them formulate how Eagle Harbor will look in relation to its watery existence going forward. As a waterfront town, they have much to consider in their planning, and they’re a town that has trouble attracting investment, like most communities of color, so we’re helping them find sources of new investments.

Initially, Eagle Harbor had minimal interest in interacting with the environmental community because, historically, most parties had approached them for their own self-interests. No one ever inquired about their needs. Really, what they wanted was to keep their town viable. And what keeps their town particularly important is their heartfelt connection with the Patuxent River. You have to honor the town’s values.

Adding to that thought, environmental justice is fundamentally important because you can’t build a movement that has hearts and minds attached to it unless justice, equity, or fairness are ubiquitous all around. I think movements are defective if they ignore injustice or, for that matter, create injustice. If you aren’t concerned with justice and equity, you run the risk of creating injustice daily. If you are blind to it, how would you know that you aren’t a part of the problem? So I think those are dimensions that the environmental community should really confront. Justice and equity are completely integral to any vision for a functioning movement likely to make a difference in the future of any of our waterways.