Patuxent Riverkeeper Fred Tutman talks race and the environment | Republished

By: Malaika Elias

As the U.S., once again, grapples with its racist past and present, we’re focusing on what we can do to build a more just and inclusive environmental movement. We acknowledge that we have a long way to travel to get there.

While we look at what must be done to make our own movement better reflect the nation, and the world, make it more welcoming to everyone, and ensure that everyone in our movement feels they have a voice, we’re focused on highlighting Waterkeepers who have been hard at work in this area their whole careers.

In this 3-part series, originally published in August of 2018, Waterkeeper Alliance Organizer Malaika Elias sat down with Patuxent Riverkeeper Fred Tutman to discuss race and the environment, Environmental Justice, and the Patuxent River.

Part 1 of 3

View the original version, published August 7, 2018, here.

Q: Who are you? Tell us a bit more about yourself and involvement with Patuxent Riverkeeper.

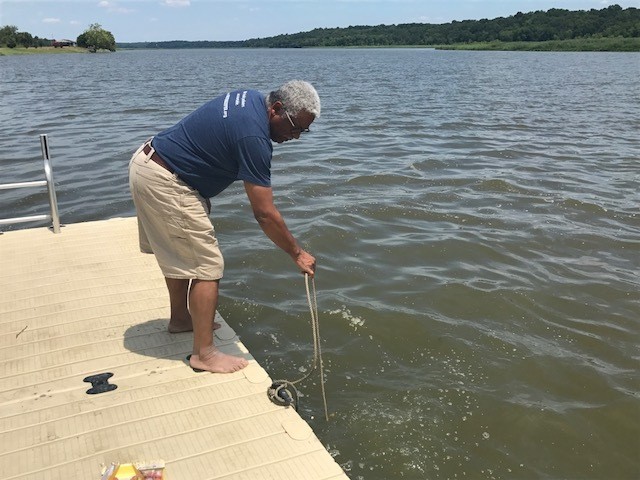

Fred: My name is Fred Tutman and I’ve been the Patuxent Riverkeeper for the past 14 years. We started in 2004, but I’ve been an activist on this river for 30 + years. The river has been a symbol and a spiritual feature of my upbringing and life in southern, rural Maryland. My family grew tobacco and watered their crops from this river. My great grandfather fished for yellow perch in this river. I swam in this river as a boy. In every respect, as much as I’ve lived in other places and enjoyed other rivers, the Patuxent is very much my home river.

The Patuxent was the first river in Maryland’s history to use the Clean Water Act to force the state to clean it up. And it’s the Patuxent River that’s responsible for the movement to protect the Chesapeake Bay. Three federal lawsuits were won in the 1960s and 70s on the Patuxent that resulted in its cleanup. When an attempt was made to memorialize those lawsuits in a remedy plan, the state found they didn’t have enough political districts on the river to get State legislation passed so the governor started the State’s Chesapeake Bay Program. So the little known truth is that the only reason people are fighting to save the Bay is because of the Patuxent River. Patuxent Riverkeeper stepped up and started the charge. Others lit the fuse, but I think it’s our job at Patuxent Riverkeeper to keep that fuse lit. Not because we are pugnacious, but because we passionately believe in the power of one and the power of many all at the same time. We fight to activate communities and empower people to defend their water and I think that’s huge. It doesn’t have to be staffed out and it doesn’t take a lot of material. It’s all about having the spine to stand up for what’s right and fight.

Q: You’ve spent a lot of your time engaging communities of color and Environmental Justice communities. What does Environmental Justice mean to you? And how are you engaging and empowering those communities?

FT: Environmental Justice to me is entirely about fighting injustice and inequality. When you say the words “Environmental Justice,” most people think you are talking about black folks or people of color. We see it in a much more pure sense. These are David and Goliath fights where people with far less power are largely fighting people with an exorbitant amount of power and money. And that can be a white, black or Asian community; any community except a rich community. You don’t find many rich communities fighting off coal-fired power plants or CAFOs or sewage discharges; those, frankly, are placed where there is less money and less power and the two seem to go together. So I would say we at Patuxent Riverkeeper are part of a social activist movement where the environment is key in our lense. We are community organizers where our sense of community is defined by the track of the river.

The Patuxent is an extraordinary river that has a lot of punch as far as defining what Maryland’s obligations are to protect its water. But I think the Patuxent’s best stories come out of the connection between people and these waterways. We try to identify and honor those connections as best we can. We frequently have Native Americans, African Americans, white people, and people of every walk telling us their stories and engaged in our Patuxent movement.

One way we bring power to these communities is through expertise. We bring legal expertise, we bring water-based knowledge, and we bring context. So for example, when we first approached and began working with Eagle Harbor (a small Environmental Justice community on the Patuxent), they told me they wanted solar panels. I called the people I know that are familiar with solar panels. Now we’re trying to put a deal together for the town and I think that’s instrumental because we are responding to what the community’s vision is. We didn’t tell them to get solar. They told us they wanted to learn more and enlist our help in finding available options. Our conversations with towns like Eagle Harbor almost always start with us trying to glean what their needs are. We sit with them at town and community meetings, listen to what they are talking about, and wait for an opportunity to be of service.

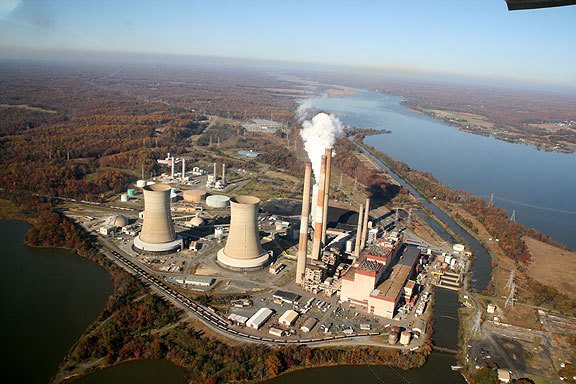

It is key that this particular town has been steeped in a legacy of racism and injustice since its founding. When beaches in the area were restricted for people of color, Eagle Harbor was formed as black enclave and resort in the 1920’s. Part of the town is a former steamboat landing site that once transshipped slaves who worked the Maryland Tobacco fields in the 1800’s. Like many places in our watershed, the context for what exists there now was shaped by the legacy of past and present disparities and injustices of various sorts. The adjacent neighbor is a massive coal burning power plant (Chalk Point) that has had numerous unlawful discharges and violations that affect the town. Just acknowledging that past context and present reality helps us connect and serve this town. It is a beautiful town with a beautiful story to tell.

When we are able to be of service, communities reciprocate. They support us in return. In the end, it’s all about them, and we connect them to each other sometimes. In the case of Eagle Harbor, we connected them to another black town, Highland Beach, who exchanged helpful information on how they had gotten solar panels and a sustainable communities designation. The town is following by example. In a sense we are building a far flung sense of community around water and environment. We’re helping them formulate how Eagle Harbor will look in relation to its watery existence going forward. As a waterfront town, they have much to consider in their planning, and they’re a town that has trouble attracting investment, like most communities of color, so we’re helping them find sources of new investments.

Initially, Eagle Harbor had minimal interest in interacting with the environmental community because, historically, most parties had approached them for their own self interests. No one ever inquired about their needs. Really, what they wanted was to keep their town viable. And what keeps their town particularly important is their heartfelt connection with the Patuxent River. You have to honor the town’s values.

Adding to that thought, environmental justice is fundamentally important because you can’t build a movement that has hearts and minds attached to it unless justice, equity, or fairness are ubiquitous all around. I think movements are defective if they ignore injustice or, for that matter, create injustice. If you aren’t concerned with justice and equity, you run the risk of creating injustice daily. If you are blind to it, how would you know that you aren’t a part of the problem? So I think those are dimensions that the environmental community should really confront. Justice and equity are completely integral to any vision for a functioning movement likely to make a difference in the future of any of our waterways.

Part 2 of 3

View the original version, published August 8, 2018, here.

Question: What does the intersection of race and the environment look like for you?

FT: The intersectionality between the environment and race is a huge topic because, to a certain extent, race and the environment are both about sense of place. Environmental problems largely flow from people’s sense of connection to their resources. What most of us think of as an environmental problem largely flows from our sense of connection to the resources around us. But sense of place and race are very different because we don’t share the same circumstances. It’s appalling to me that people would assume that we all want the same thing. I hear this constantly from white environmentalists. It’s almost a placeholder for not talking about what we all want—many white environmental spaces have already predetermined what the environmental movement as a whole wants and needs. That’s greatly unfair and non-representative to communities of color because we are certainly capable of articulating our own vision for the environment and we have our own connections to “place” which may not be familiar, accessible or even relevant to white folks who don’t usually share our experiences or stand in our shoes.

With intersectionality, it’s important to remember we are all talking about the same thing—the environment. The environment, to me, is all encompassing or holistic—it’s what’s all around you—including the socially leveraged disparities. So if we’re coming from different places, we’re clearly not working on the same source problems or root causes. There needs to be bandwidth within these movements to tackle issues from divergent perspectives, to assure representation even for issues that may fall off the beaten path from mainstream environmentalism.

One issue that comes to mind is urban investment. It costs money to adopt some of the environmental practices we all promote. I took the Mayor of Eagle Harbor to the Black Communities Conference at UNC Chapel Hill a couple months ago and people from all over the country—black towns, black mayors, black functionaries—attended and exchanged knowledge. All of them have reinvestment problems that are different than the ones typically found in affluent white suburbs. Black towns and black communities have issues retaining their autonomy and self-determination when trying to influence how these communities will sustain going forward. The conference was fascinating and inspiring. But it was obvious that everybody there had environmental problems enmeshed among all the other problems they need to face.

Gentrification is a horrific example of how places are losing their self-determinism through real estate capitalism, which contorts property value in a manner that drives low-income populations out of the community so realtors can recruit affluent people that they can overcharge. It’s a formula. And black communities are usually fighting these battles without substantial support or recognition that it is a real issue. How can one pursue a community vision if there are outside forces usurping the community? But people outside of these issues usually don’t even see it as a problem.

I hear this all the time—the presumption that worse-off communities are responsible for their own fate. So if it has a brownfield, it’s because people in the community didn’t have enough initiative to clean it up? Because there was a lack of interest in protecting themselves? It’s shocking to hear some environmentalists ask why folks in blighted minority communities don’t clean up their neighborhoods—won’t install rain barrels, etc.— as though somehow it rests entirely upon us to redeem unfavorable uses that proliferate in our communities as part of a pattern. That’s not the residents fault as much as it is the profiteering, redlining, and other malicious behavior that feeds the ruination of such places, and the economic systems that steer renewal of precious resources away from these places that are facing huge and disproportionate environmental health problems.

I’ve also heard people in the environmental community argue that restoration money and public money should go to fix-up greenfields instead of brownfields as a better use of our funds because the problems are too serious in those worse-off communities for us to have a meaningful impact with the limited resources available. These are rationales that I think are especially disingenuous, but they are also arguments that drive people of color away from environmental movements. They realize there is sometimes less value and power to be found for us in conservation movements beyond mirroring what the prime players are talking about or concerned about.

There are really fewer forums and opportunities for us to assert our environmental views and knowledge without being seen as disingenuous or off message, if it reflects a perspective disconnected from what the prime participants care about, or are funded to work on. But it’s shocking if anyone thinks we’re going to clean up the environment with only white people doing most of the work! We have to engage other people, populations, and ideas because no one ethnic group or class is up to it alone, and no one group is the sole source of ingenuity, intelligence, or passion on these issues. At every Waterkeeper Alliance conference I am stunned by what the international programs bring to the table as far as solutions, ideas, and innovations. We have to capture all of that, and frankly that sort of environmental movement looks quite different than the majority of the ones we already have. I think that’s where we run into trouble with “diversity.” It is the pushback from the majority point of view. Change is necessary and that change requires changing some paradigms within these movements—not necessarily change within the subject and suffering populations.

We need to acknowledge that there is a widespread cultural dissonance within America and it affects the environmental movement as much as it affects every other hot topic in public affairs. We have to address the fact that people associate environmentalism with being white. That’s the norm and the expectation and that needs to change. These movements are mostly designed and accustomed to serving people who are white. It hasn’t occurred to them sometimes, except maybe as an afterthought that they need to serve anybody else. And that’s truly the behavior we need to change as well.

Of course when we try to change that, some white environmental spaces think you’re taking something away from them. A more inclusive movement challenges their accustomed role. The environmental movement is about people of color (or should be), it’s about people in cities, it’s about poor people, and it’s not just about people in raw nature and lovely places. It’s about people who may not love nature in quite the same way you do. Ultimately it’s about everybody!

We have to recognize that not everybody wants all the same things we want in precisely the same way. That’s what real diversity is! We have to be broad-minded enough to be willing to adjust the agenda such that we can have conversations with people who love and treasure the environment, even if they don’t necessarily see things our way.

Part 3 of 3

View the original version, published August 14, 2018, here.

Q: You wrote an article titled, “Why Green is not the new Black or Brown” in 2012. Do you still feel the same sentiments now in 2018? If so, what is the way forward for inclusivity in the environmental movement?

FT: I do believe in that article and what I had to say because it drew from my own epiphany that, after some 30+ years of environmental work, simply acknowledging that race is important to the environmental cause was an important step. In effect, taking off the blinders and getting real. As long as the pretense prevails in some quarters that race is irrelevant, unimportant, or divisive, or that diversity comes from a script—then it’s impossible to get on a reality check with a community of color or an Environmental Justice community.

We (people of color) don’t have the same rankings or voice in the environmental movement. Sometimes we feel like guests instead of full partners. As much as I think in principle that we all need to be in the same movements—because we’re all earthlings—we are also co-inheritors of this racial tapestry rooted in slavery and colonialism and all kinds of other “isms.” We don’t all have the same means and mechanisms toward empowerment or self-actualization. I believe that sometimes people of color give up our power just by joining movements that don’t reflect us, don’t represent us, and actually are not that interested in hearing our views unless they comport with the broader, dominant, white environmental movement. I’ve struggled with this problem along with others and a lot more struggle is needed. The idea that there is environmentalism for white folks and environmentalism for black folks does not ring true to me.

But I suspect that the struggle that some white organizations have in trying to diversify is because it’s never occurred to them that people of color are actually boycotting them. Sometimes we are staying away because we don’t see power for ourselves, we don’t see relevance to our communities or circumstances, and we don’t see opportunities to address any or many of the local problems that face our communities. This is quite the opposite of the same old cliché that says “black folks don’t care about the environment” — which is a very expedient and reductionist conclusion to draw. Everybody cares about their own environment, but sadly they just may not care so much about yours! I find that many people who express these claims to me don’t have many connections in ethnic communities. They lack a diverse framework of friends to bounce their ideas off of. How many “diverse” people do they actually know where they can speak openly and intentionally about these things and get some feedback?

It bothers me that sometimes people fear I’m somehow arguing for a movement that doesn’t care about white people’s problems. That hurts. My views on race are formed from a deep understanding of injustice and a lifetime of being black in America. I know how costly injustice is in our society. Not just economically costly, but spiritually and practically exhausting. Race and class issues are tearing this country and society apart and yet these are subjects we have trouble talking about. Race in particular is a touchy subject. It’s extraordinary that some white people believe the “Black Lives Matters” movement is somehow arguing that white lives are less valued. But I think it is the same sort of thinking that seems to imply, at times, that by uplifting the environmental fights and plights of black communities in our work, we’re somehow taking something from white communities? That’s extremely troubling.

In terms of a way forward, I think sometimes including communities of color is as simple as providing the space and welcoming the input. Making it clear that you are here to serve the people—not just recruit yes-men and -women. Getting folks on your bandwagon requires a willingness to share the bandwagon. At Patuxent Riverkeeper, we started having black communities suggest people to be on our Board of Directors, asking us what help we needed, and how they could get involved. It’s an organic process and you have to be willing to make eye contact in order to build trust. Invest yourself in fairness and equity and it makes for really powerful and magnetic messaging! I think that was a key takeaway for us. We’ve done several iterations of integrating different communities in our work, like having shows and events at our office that were planned by our Native American allies and partnering to create programs that serve diverse demographics in our watershed work. We just provide the space and pitch in where asked.

The key takeaway here is that diversity, equity, and inclusion is not so much about a head count of how many people of color you have—it’s about what’s representative of communities. It’s time to take off the blinders. There’s a whole lot more happening that connects to race, place, and the environment that the big and very familiar environmental movement aren’t touching. That is lost capital, potential, and energy in a movement that needs all the energy, ideas, and people power it can get. Kudos to those that are tapping that potential—we need more of that. A truly diverse environmental movement, it seems to me, is a much more exciting and interesting movement to be a part of.