Cook Inletkeeper’s Fight Against Climate Change for Wild Alaskan Salmon

By: Bart Mihailovich

Cook Inletkeeper Bob Shavelson has been fighting climate change in Alaska for twenty years.

From melting sea ice and receding glaciers to warming salmon streams and eroding coastlines, Alaska is on the front lines of rapid climate change.

Inletkeeper started recruiting a coalition of scientists, Alaska Natives, fishermen, and legislators by focusing on the one thing that connects all Alaskans: wild salmon.

Salmon mean subsistence for native tribes, economic opportunity for fishermen, a prime attraction for the tourist industry, and a common link all Alaskans can reach into their freezers and find.

But salmon are cold-water fish, and warming streams make them more vulnerable to pollution, predation, and disease. Shavelson recognized, back in the 1990s, that rising global temperatures could destroy their habitat.

Shavelson knew he’d need a dataset to underpin that case, so Cook Inletkeeper staff started logging temperatures in 48 salmon streams in southcentral Alaska.

The results: In-stream temperatures now routinely violate state and federal standards designed to protect migrating and spawning salmon.

Armed with the data, Inletkeeper built a communications and organizing infrastructure, called the Alaska Climate Project, around the idea that increased fossil fuel production posed an existential threat to wild Alaskan salmon.

Alaska has long been an oil and gas state; it also has up to half the U.S. coal reserves, accounting for roughly one-eighth the coal reserves in the world. As coal prices remained strong in the mid-2000s, more than a dozen coal mining, combustion, and export projects were proposed around Alaska.

Keeping that coal in the ground would be a win in the fight against climate change.

So Inletkeeper used its climate science to show Alaskans that climate change threatened wild salmon. As part of the work, the Alaska Climate Project started an outreach campaign that ultimately reached 500,000 Alaskans.

Once people understood how vulnerable salmon are to rising temperatures, the group emphasized that new coal projects would mean more carbon in the atmosphere, and worsening climate change. They targeted decision-makers, pressuring them on permitting decisions around coal mining, combustion, and export facilities.

The goal: Make political and permitting support for coal production, burning, and transport unpopular and untenable.

To achieve this, supporters from 12 native tribes highlighted the threats coal mining posed to historic artifacts and their salmon subsistence culture. Scientists focused on how rising temperatures have harmed salmon elsewhere, emphasizing that Alaskan coal would contribute to even higher temperatures.

Supportive legislators made the case that coal needs too many subsidies to work in current market conditions, and that Alaska’s world-class renewable energy assets make clean energy development a better path toward energy independence.

Commercial and sport fishermen argued that salmon are the lifeblood of our local coastal economies and that coal mining threatens their livelihoods. And finally, everyday Alaskans drove home the point that coal development and climate change directly threatened the salmon that fill their freezers each year.

These activists spoke up at tribal gatherings, scientific conferences, town hall meetings, during permitting comment periods, at legislative hearings, in opinion pieces and letters to the editor, and on social media. Over ten years of the campaign, more than 150,000 Alaskans signed petitions, wrote letters, made phone calls, or attended hearings or meetings.

Public engagement reached its highest level last summer, as Alaska witnessed a historic heatwave.

This work helped stop four massive proposed coal mines in Chuitna, Wishbone Hill, Western Arctic Coal, and Canyon Creek and their associated export terminals, as well as two large coal export terminals, which would have pumped out more than 25 billion tons of carbon into our atmosphere.

As it did the work, the Alaska Climate Project built a database that now includes more than half of Alaska’s population. This database, which includes an on-the-ground canvas and phone banking network, has resulted in tens of thousands of door knocks and one-on-one conversations. Together, this education and activism — supported by strong science — has resulted in a demonstrable shift in public opinion toward climate change, leaving the campaign well positioned for its next battle: The focus on oil and natural gas, how those relate to climate change, and what they mean for the state’s beloved wild salmon.

It’s time to demand action on climate change!

Devastating floods. Blazing wildfires. Crushing droughts. Climate change is already taking a terrible toll on our planet and our communities. As part of Climate Action Day, we’re calling on everyone to join United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres in calling for universal action to ensure our children — and theirs — have a healthy planet to call home.

“We need more concrete plans, more ambition from more countries and more businesses,” António Guterres says. “We need all financial institutions, public and private, to choose, once and for all, the green economy.”

With the U.S. leaving the Paris Accord, it’s time for individuals to stand up. Join us in demanding action on climate change. Show your support by signing here.

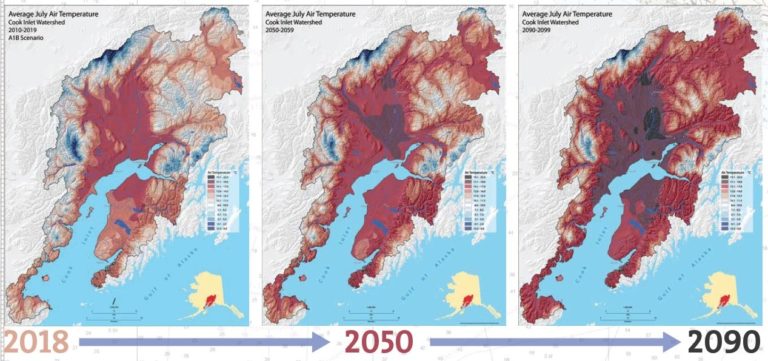

Feature image: Range of scenarios exploring future climate change, by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change created in cooperation with Scenarios Networks for Alaska + Arctic Planning and The Nature Conservancy in 2010.