Waterkeeper groups throughout North Carolina completed a blitz of water sampling this fall, drawing samples in watersheds from the mountains to the coast. Their results illustrate two things: Why the state needs a freshwater standard for E. coli, a dangerous bacteria that can cause life-threatening disease — and the good work a strong Department of Environmental Quality can do.

Currently, the state of North Carolina has no freshwater standard for E. coli, and no state testing regime to look for E. coli in freshwater. That leaves North Carolinians vulnerable to dangerous exposure.

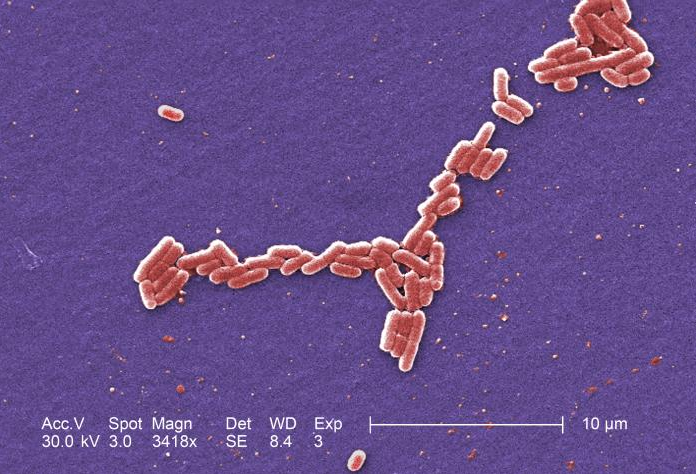

Escherichia coli, or E. coli, is part of a family of bacteria that live in the intestines of mammals. While many forms are harmless, six groups of E. Coli cause illnesses, and the presence of E. coli is an important indicator other pathogens may be in the water.

To determine how prevalent E. coli is in North Carolina’s river basins, Waterkeepers around the state took 36 samples from nine watersheds in September and October, then sent them to state-certified labs for analysis.

The recent statewide round of water sampling was a follow-up to testing Waterkeepers did in the spring, when they tested for bacteria at 34 sites across the state, and found 13 sites (including locations in the Catawba, Cape Fear, Broad, Waccamaw, and Haw watersheds) where bacteria levels exceeded the state standard for fecal coliform, another bacterial pathogen.

The results of Waterkeepers’ fall sampling: In 12 of the 36 samples analyzed, or 33 percent, the laboratories found E. coli levels that exceeded the EPA’s most protective freshwater standard of 320 colony forming units (which estimate the number of viable bacteria in a sample) per 100 milliliters.

Waterkeepers found levels in excess of the EPA standard in five watersheds around the state: The Broad, Tar-Pamlico, Yadkin, French Broad, and Lumber.

Off the charts

The highest reading was from the French Broad basin, where one sample from a small, unnamed tributary to Jonathan Creek returned a result of 363,000 colony forming units per 100 milliliters — more than 1,100 times the EPA standard.

“This is the highest sample I’ve ever taken anywhere,” said French Broad Riverkeeper Hartwell Carson.

Another, taken the same day from a different location in the French Broad basin, returned a result of 19,700 colony forming units — 61 times the EPA standard.

The good news in the French Broad watershed is that it has a strong regional office of the state’s Department of Environmental Quality. The French Broad Riverkeeper had earlier reported the site, which is downstream from a few dairy farms, to the environmental regulator, which followed up by methodically collecting its own data about water quality.

When a group of local farmers asked for a meeting with area politicians and the DEQ, officials from the agency presented a thorough scientific overview of the problem near the farms — and everyone who attended agreed they needed to start working toward solutions.

“They built a really good scientific case that was impossible to ignore,” Carson said.

The farms involved won a $500,000 grant from the Clean Water Management Trust Fund under “directed appropriations,” meaning elected officials chose the grant recipient. The money will go toward fixing drainage issues at the farms, keeping waste out of the waterways.

The two farms involved have “a bunch of medium to small issues that add up to a big issues,” Carson said. “DEQ didn’t find one giant pipe pumping animal waste in the stream; it was like a bunch of different medium-sized problems.” (In contrast to this.)

“There’s a pretty big water quality problem in Haywood county, in this watershed,” he said. “A lot of it is a lot of small problems adding up.”

“We have a responsive DEQ field office,” Carson said. “It’s amazing what we can accomplish we everyone is working towards the same goal.”

A matter of public health

It’s equally clear what’s missing when the state’s environmental regulator doesn’t step up. That’s been the case on a freshwater E. coli standard. Deadly outbreaks of E. coli around the country show how important monitoring is. Without a standard, anyone swimming in the state’s freshwater is vulnerable to this dangerous pathogen.

Frustratingly, North Carolina has a freshwater standard for fecal coliform, but none for E. coli, a decision that isn’t supported by science.

EPA conducted a series of studies in 1972 to assess the relationship between gastrointestinal illnesses and recreational use of sewage-contaminated water. The studies demonstrated that E. coli are good predictors of gastrointestinal illnesses in fresh waters, while fecal coliform is not.

“We knew 50 years ago that basing recreational water quality standards on fecal coliform was not aligned with the best available science,” a consortium of environmental groups including Waterkeeper Alliance wrote in a comment letter to the state as part of North Carolina’s triennial review of water quality standards

“Sadly, on the freshwater bacteria standard, DEQ is relying on outdated science,” said Will Hendrick, a staff attorney at Waterkeeper Alliance. “The state should adopt the EPA recreational freshwater standard for E. coli, and the state should test our waters to make sure they meet that standard. This is a matter of public health. It shouldn’t be up to citizen scientists from a non-profit to do this testing.”

“When the DEQ has the staff it needs, the resources it needs, and the drive to do the right thing, it can help make the state’s watersheds healthier for everyone,” Hendrick said.