North Carolina Water Sampling Reveals High Bacteria Levels near Industrial Animal Farms

By: Will Hendrick

In North Carolina, we love our waters. And as the summer heat approaches, many of us look forward to a dip in the local swimming hole, a paddling adventure, or a fishing outing on one of the state’s many rivers, lakes, and streams. We should not have to worry about whether swimming or paddling in North Carolina’s waters is safe.

This spring, North Carolina Waterkeepers conducted surface water sampling to evaluate the impact of industrial animal agriculture operations on North Carolina’s waters. Throughout April and May, trained personnel collected water samples within their respective watersheds and submitted them for analysis by state-certified laboratories. The lab analysis confirmed the presence of high levels of bacteria–i.e., fecal coliform and Escherichia coli (E.coli)–associated with animal waste, showing that concentrated animal feeding operations threaten the recreational use of North Carolina’s waters.

Why Test for These Bacteria?

Disease-causing microbes, or pathogens, are impractical to monitor directly because they may exist in small amounts and their detection can be difficult and costly. Accordingly, water quality is often assessed by evaluating the amount of “indicator bacteria” in a water sample. Fecal coliform and E.coli as two such indicator bacteria.

Fecal coliform bacteria are organisms that live in waste material excreted from the intestinal tract of warm-blooded animals. The most common type of fecal coliform bacteria is E.coli. The presence of these indicator bacteria in high amounts correlates with the presence of disease-carrying organisms or other pathogenic bacteria and viruses.

North Carolina water quality standards use fecal coliform as an indicator bacteria for freshwater. Under state rules, fecal coliform in fresh waters “shall not exceed a geometric mean of 200/100ml (MF count) based upon at least five consecutive samples examined during any 30 day period, nor exceed 400/100ml in more than 20 percent of the samples examined during such period.” Notably, guidance from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency suggests that E.coli is the best indicator of health risks posed by contact with waters during recreational uses like swimming, paddling, and boating. In 2012, EPA recommended using E.coli as an indicator of fecal contamination for freshwater and suggested a geometric mean of 100 cfu/100 mL and a requirement that no more than 10 percent of samples exceed 320 cfu/100 mL.

What Did We Find?

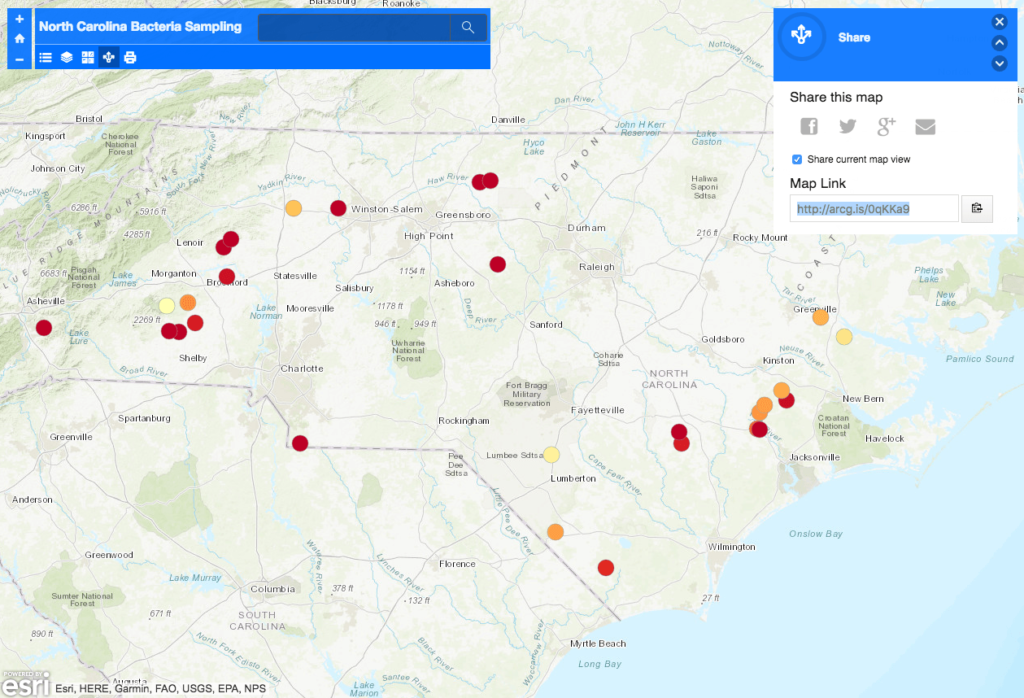

Waterkeepers tested indicator bacteria at 34 sites across the State in watersheds from the mountains to the coast.

During the coordinated sampling exercise, we observed bacteria levels as high as 120,980 CFU/100 ml for E. coli and 121,000 cfu/100ml for fecal coliform. At 13 sites (including locations in the Catawba, Cape Fear, Broad, Waccamaw, and Haw watersheds) bacteria levels found in five samples collected over a 30-day period exceeded the State standard for fecal coliform. These exceedances were reported to the Division of Water Resources, the entity with the Department of Environmental Quality that is tasked with protecting our waters for their designated uses.

The results suggest the need for greater vigilance and emphasize the importance of citizen science to supplement water quality monitoring performed by state agencies. “People swim, paddle, fish and more in these waterways and should not have to be fearful that contact with the water could make them sick,” said Sam Perkins, the Catawba Riverkeeper. “Every child deserves to have a creek where they can safely play, explore and fall in love with the outdoors, yet bacteria runoff has rendered creeks polluted and potentially unsafe for human contact.”

Why Does It Matter?

Recreating in waters with high levels of fecal coliform bacteria increases the chance of developing illness from pathogens introduced through bodily contact. Diseases and illnesses that can be contracted in water with high fecal coliform or E. coli counts include hepatitis, gastroenteritis, typhoid fever, dysentery, and gastroenteritis. The higher the level of colonies of fecal coliform and E.coli found in the water body, the higher the potential health risks are from exposure.

In addition to indicating potential human health risks from exposure, high levels of fecal coliform and/or E.coli are associated with many long-term negative effects to the waterbody and surrounding environment. Untreated fecal material adds excess organic material to the water. This can feed algae blooms, which lead to serious water quality issues by depleting oxygen levels in the water column, threatening fish and other aquatic life.

Why Focus on Animal Agriculture?

A significant amount of fecal coliform bacteria is released in the wastes excreted by animals. This can be a serious problem in waters near hog facilities, dairies, and poultry operations where waste is not properly contained. There is an increasing number of North Carolinians that live near these CAFO facilities and utilize these contaminated waters for swimming and fishing with their families.

Moreover, the regulation of animal operations is grossly inadequate to prevent waste from adversely impacting our waters. Swine operations are permitted as “nondischarge” facilities, but waste mismanagement at these facilities often introduces pollutants into surrounding water bodies. And poultry operations are not even issued permits which means the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality does not even know where these operations are located. They are also allowed to spread their waste under the presumption that rain falling on the waste will not cause it to runoff into waterways.

There are, of course, other sources of fecal coliform and E.coli in our state, including municipal wastewater treatment systems. But those plants are required to operate under federal permits requiring operators to treat their waste before discharging it into our waters. And at least, because those sources have strict monitoring and reporting requirements, members of the public can learn about polluter practices through public records requests if our regulators turn a blind eye.

What Next?

Waterkeepers throughout North Carolina will continue to monitor the impact of animal agriculture on our waters. But the public can help us increase protection for our waters. Right now, the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality is accepting public comment on the State’s water quality standards. The agency is explicitly inviting input on whether or not to adopt new bacteria standards consistent with EPA’s recommendations. Now is the time to let our State agency know that we demand adequate protection of recreational uses of North Carolina’s waters. You can submit comments until July 16 by emailing [email protected]. You can also attend one of the public hearings to deliver oral comments.