By Andrew Kelly, Yarra Riverkeeper

Australia is in the midst of a devastating summer of bushfires, which followed years of record-breaking heat and drought. When the fires hit, there was an unprecedented lack of water in the landscapes of southeastern Australia; our once-spongy soil was already as dry as ashes.

Despite tireless frontline firefighting, fires were contained only once the drought broke for many areas in early February 2020.

But our fire season isn’t over.

Why fires matter to Waterkeepers

Fires thrive on drought and contaminate remaining water supplies with ash.

Fires expose waterways to savage scouring and erosion.

Hot rivers trigger fish deaths.

Privatizing water supplies through licenses to coal mines is an ironic feedback loop: more emissions, less water, more fires, less water.

To prevent fires, we need more water retained in the landscape, more groundwater, and healthy rivers and creeks.

As Australian Waterkeepers, we recognize a major impact of climate change is the drying of the Australian landscape, leading to ever-increasing fire risk.

We need to manage water better.

We need political commitment that recognizes action on climate is integral to the health of our waterways, which in turn underpin all human functions and nourishment.

We’re on the front lines of the climate crisis

Australia, a hot and dry country, is extremely vulnerable to climate change.

All of our hottest years, bar none, have been in the past decade, and 2019 was leading the list, with an annual national mean temperature that was +1.52 °C above average, sailing past recent record-breaking years. Meteorologists last year had to devise new colors to show extraordinarily high Australian temperatures on weather maps.

During the bushfires, people worldwide reached out to our Waterkeepers checking on our safety, and questioned how Australia might change its climate politics as a result of the fires.

The subject has become a wedge issue in Australia, where a minority of hard-right climate-deniers, closely tied to fossil fuel companies, can stall action in closely split parliaments.

The bushfires have forced a reluctant acknowledgement of climate change by the Australian government.

Still, despite catastrophic loss of life, species, towns, and economies, the Australian government still does not fully acknowledge that Australia, which has the highest per capita carbon dioxide emissions in the world, must be in the vanguard of reducing emissions, rather than the baggage train.

Settlement changed the landscape

European settlers have been reshaping Australia’s landscape since they arrived in 1788. Settlers spread rapidly across the continent, pushing indigenous people to the margins of society, and radically altering land management practices that had maintained biodiversity and stability in the land since the end of the Pleistocene. The unintended consequences of these changes have cascaded through time.

Fire was a key management tool for indigenous people, who used “cool burning,” controlled fires in small patches to reduce leaf and forest-floor litter without damaging soil structure. Australia’s indigenous people cooperated to devise yearly fire plans based on the likely weather and patterns of previous burning. The soil, soft and open, retained moisture like a sponge, inhibiting the potency of fires.

Traditional burning kept a portion of the landscape as open woodlands, which early Anglo settlers compared to an English parkland, through which you could gallop a horse. But settlers prevented the use of landscape burning so their fences and outbuildings were not damaged. As a result, undergrowth filled in the open woodland and trees grew more densely. The change happened rapidly, and was commented on at the time by people such as the explorer Alfred Howitt and Governor La Trobe of Victoria. Fire fuel loads built up.

Flash forward to the present, where climate change is compounding the problem of dry fuel buildup in an equally dry landscape.

What is ‘normal’ these days?

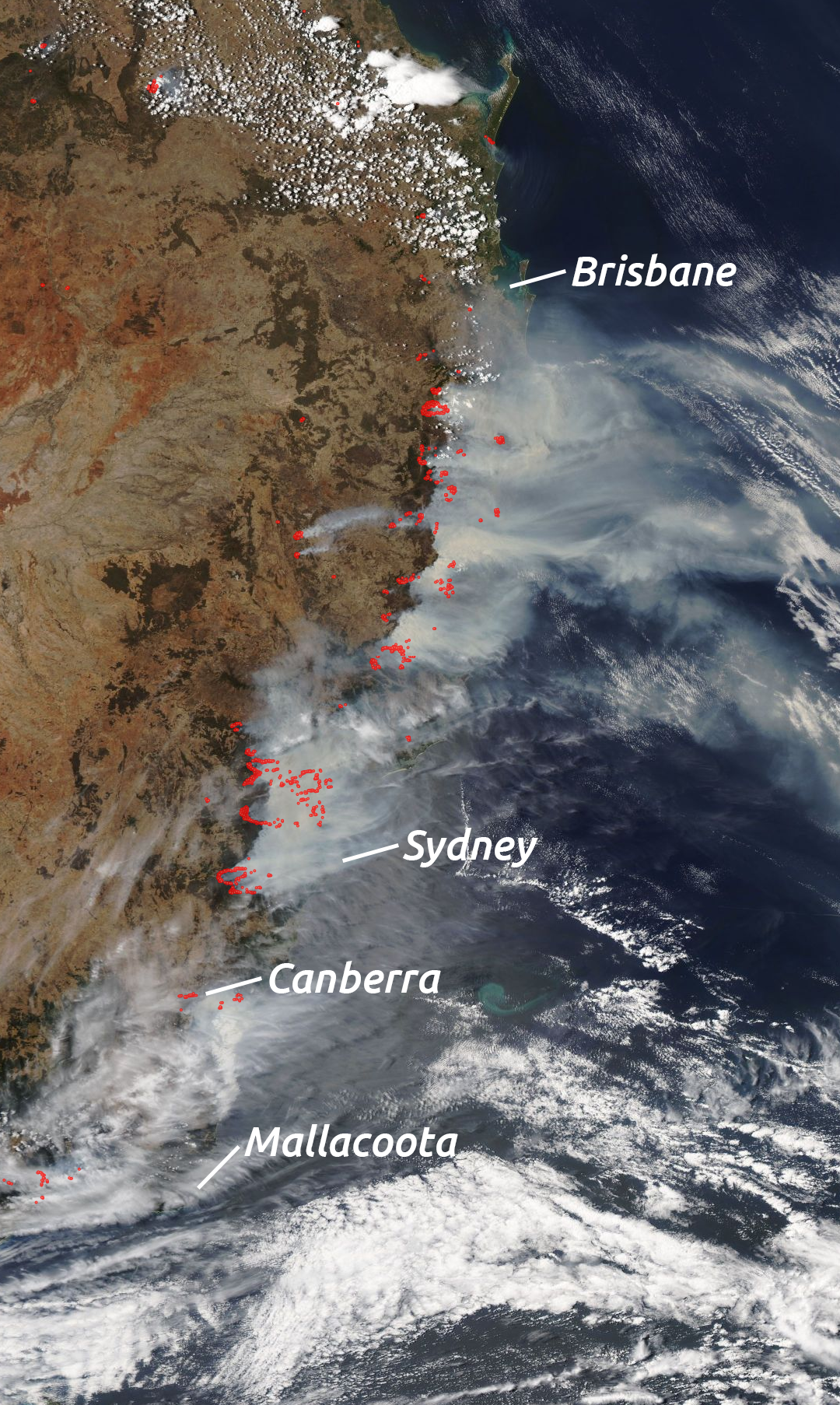

The extreme bushfires in this season began in August and September 2019, in the states of Queensland and northern New South Wales. Fires continued to ignite over the coming months across eastern Australia. Later in the seasons, fire also burnt in the west.

The most aggressive wild fires historically occurred in February. This season, the worst fires started in late December, when many Australians were holidaying in rural areas, forcing complex evacuations.

Australia, like California, now has a longer and more intense fire season. We’re four months in, at the time of writing, and fire season is still not finished.

The fires have burnt over 10 million hectares and killed over a billion wild animals.

Will the government be shocked into action?

The country is in shock. The capital city Canberra and our largest cities, Melbourne and Sydney, have been shrouded in smoke for days on end. Public servants in Canberra were asked to stay home to avoid the impact of smoke on the worst days.

There has been a failure on all political sides to acknowledge the impact of climate change. The Liberal-National Party, our equivalent of U.S. Republicans, has been afraid to pursue adaptation, as it looked like an admission that climate change was real, which a portion of the party vehemently denies. The Nationals support jobs in regional areas of Queensland where there are coal mines, and also receive funding from fossil fuel businesses. On the left, there has been a fear that talking about adaptation will limit the action on reducing emissions.

The Australian government is now, at last, willing to look at landscape adaptation to cope with inevitable climate changes, and has appointed a bushfire Royal Commission to make recommendations.

As Waterkeepers, we call on the government to show leadership on emissions reductions. Despite Australia being one of the most vulnerable countries to the impact of climate, the government has sought to wriggle out of clear commitments by claiming notional carry-over credits, and sought to undo global action on emission reductions.

That must change.

As Waterkeepers, we feel that what is required is not only an assessment of the causes of fire, but the need to “heal country” and recognize how the landscape has altered without traditional burning. We need to change the way we manage our landscape. We need to understand how First Australians managed the landscape, and work with them to apply this thinking in our new circumstances.

Feature image: Blue Mountains bushfire (Gospers Mountain, NSW Australia, December 2019)