The Karnali River – Nepal’s biggest and last free-flowing river, and the sacred headwaters of the Ganges – is threatened by a massive dam

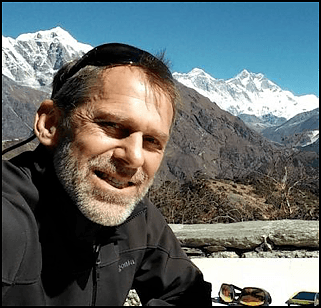

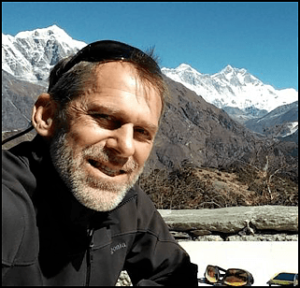

Megh Ale (pronounce “Ah-lay”) is a patient man. His eyes twinkle, the corners of which turn up into a soft smile almost all the time. He used to be a monk before he started his rafting, adventure travel, and river conservation endeavors. Patience is a virtue in Nepal if you are a river conservationist, but a sense of alarm is also present in Megh’s face and voice. The country has about 6,000 rivers and streams, and every single river is dammed except one.

That’s right — one.

Megh Ale is trying to save it.

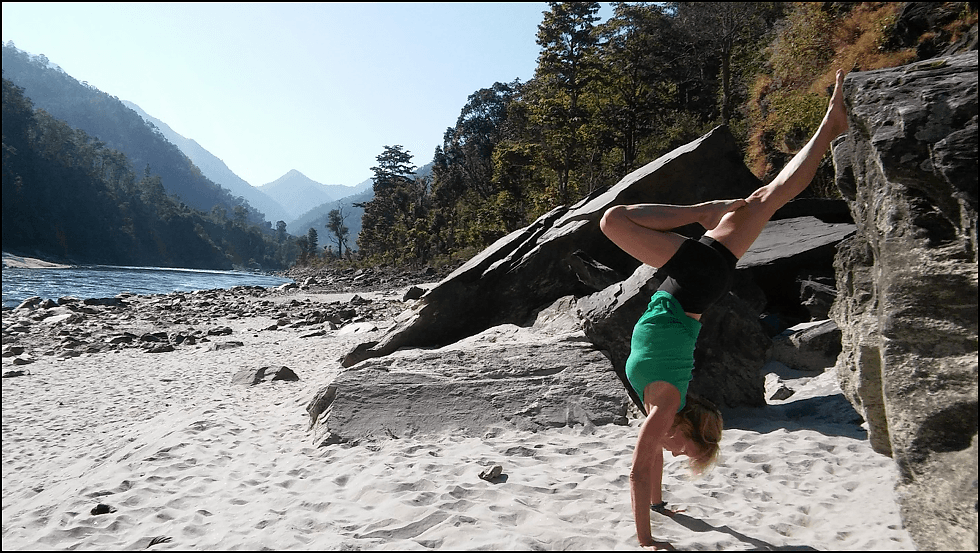

The Karnali River begins in the Himalaya Mountains on the Nepal-side of the Tibet border across from holy Mt Kailash. The spiritual center for four eastern religions – Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Bon – Mt. Kailash is believed to be where the Hindu’s Lord Shiva lives and sits in a state of perpetual meditation. But the Karnali River itself seems to never meditate. It rages and flows down the canyons of Western Nepal in a constant state of motion, its glacier-fed blue-green waters glistening in the sun.

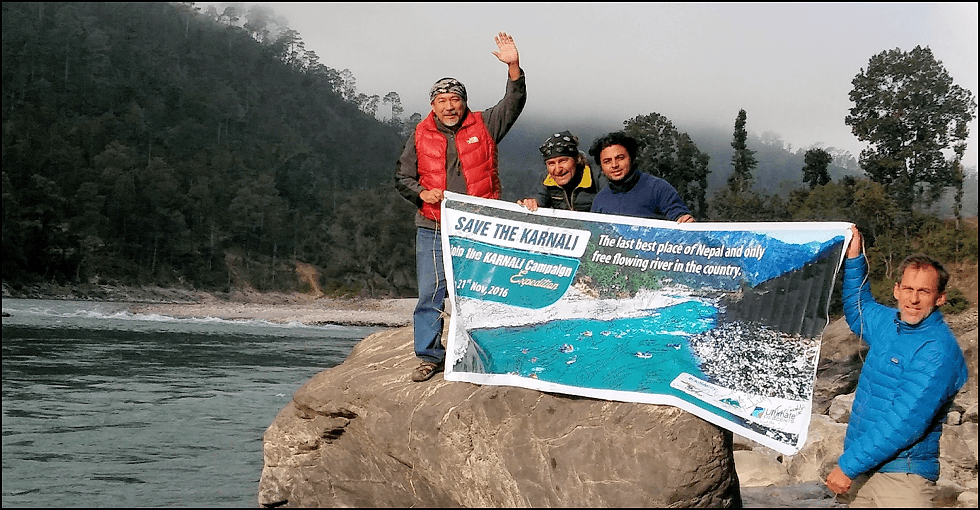

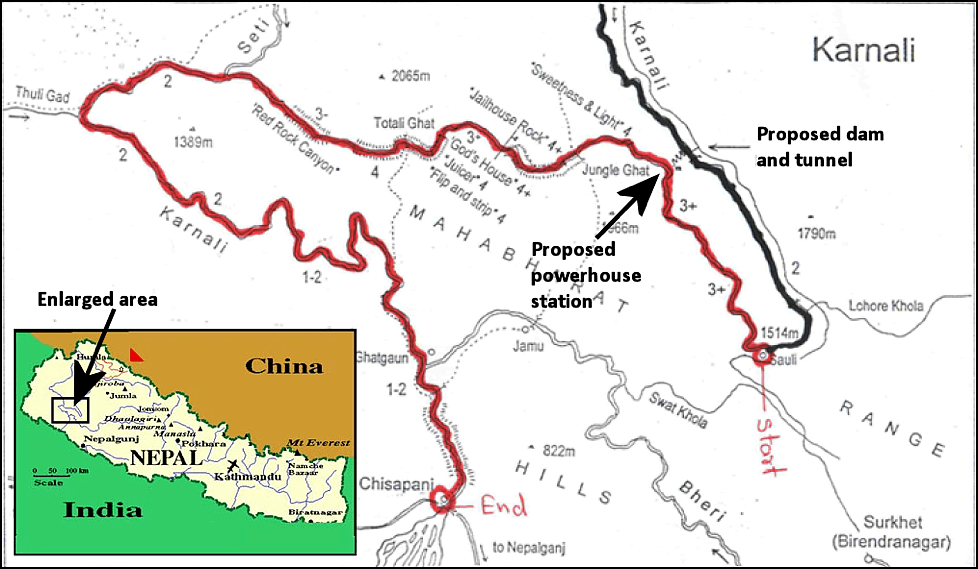

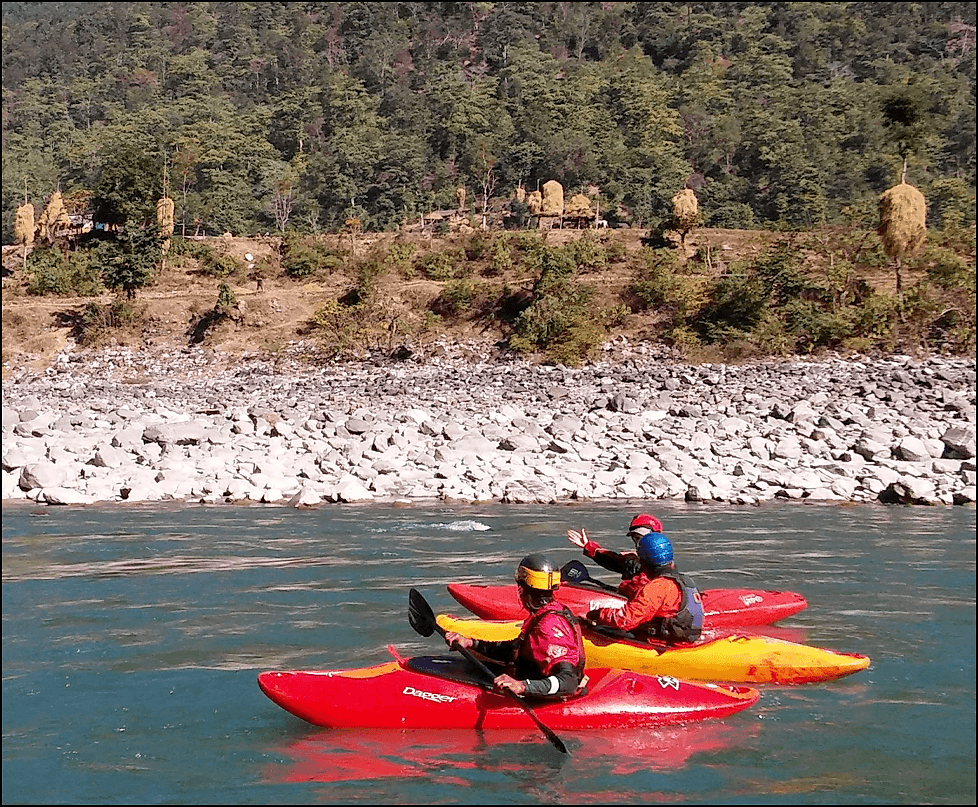

We visited in the first week of November 2016, which is the dry season in Nepal. Led by Megh and his team at his rafting company, Ultimate Descents, twenty one of us international adventurers – from a total of ten different countries – launched an eight-day raft trip on the Karnali as the inaugural “Karnali River Waterkeeper Expedition.” Megh has helped lead the river conservation movement in Nepal for several years at the “Nepal River Conservation Trust” which he co-founded. In 2016, Megh joined with the international Waterkeeper Alliance to create several local Waterkeeper organizations in Nepal, with Megh leading the effort to protect the Karnali.

On our first day at the put-in, five of us woke up very early and drove the bus 18 miles upstream to the proposed dam site of the “Upper Karnali River Dam” in the village of Daab. A private Indian engineering firm, GMR, that proposes to build the dam has built a small headquarters in Daab, their six new modern buildings contrasting dramatically against the traditional mud and slash-roofed homes of the villagers.

After arriving in Daab, we quickly and quietly snuck down through the village to the bank of the Karnali River and unveiled the “SAVE THE KARNALI” banner for a photo op. “The last best place of Nepal and only free flowing river in the country” says the banner, but GMR proposes to dramatically change that by building a 520-foot tall dam near where we are standing. The project is one of several proposals on the Karnali – including a competing proposal to build a 1,345-foot tall dam, which would be the world’s tallest. The proposals have unleashed a massive controversy in Nepal and have increasingly drawn international activist and media attention.

After our photo op, we drove back to the put-in at the village of Sauli, which would be the last large village and the last road we’d see for eight days. Most of the canyon downstream from Sauli is accessible only by foot-traffic and is inhabited with small farming villages. The crew packed all the boats while we were up at the dam site in the morning, so we quickly eased our expedition into the water and left the bus and the village behind us.

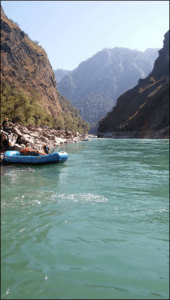

As our armada of three large rafts and three kayaks began the journey, I could see the blade of my paddle down through the Karnali’s milky water. The Karnali’s blue-green water is clear down to about six feet – below that it’s not dirty or polluted, but clouded by the dissolved minerals that flow down from the Himalayan glaciers.

Wet season in Nepal – when the monsoons drench the entire country – is in June, July, and August. The climate is dry most of the rest of the year, with September, October, and November being the driest and sunniest.

At the put-in, we estimated the flow of the Karnali at 20,000 cubic feet per second which is probably one-fifth of the wet season flow. High water mark on the river was ten feet above us and had scoured the banks of the river clean of vegetation and most debris. It is that high water that the hydroelectric dam companies are hoping to divert and harness to generate electricity. For now at least, the financial, political, and ecological details of the proposal remain completely unharnessed, much like the wild Karnali itself.

The “Upper Karnali River Dam” proposal is to build what’s called a “run of the river” hydroelectric project that would divert almost all of the water out of the river, bore a massive two kilometer-long tunnel downhill through a mountain, place a powerhouse at the bottom of the tunnel to generate electricity, and run the water down through the tunnel and powerhouse and then back in the river. About 44 miles of the Karnali River would be almost 100% drained. Because the Karnali River does a long circling switchback in that area, the proposed project would maximize the power created by the fall in the river, while minimizing the length of the tunnel, thereby creating a relatively cheap source of electricity. Indeed, the project has been eyed for over two decades, but dueling proposals and politics generating a lot of controversy have ground the project to a halt.

One proposal on the Karnali River is for the Nepal government to own the project and the electricity and build the world’s tallest dam. Another proposal – which has taken a big step forward – has secured an agreement between the Nepal government and the Indian engineering firm, GMR, and would ship 75% of the electricity to India. So far, that second proposal has stalled for lack of funding and lack of political backing – it would cost nearly a billion dollars (U.S.), and the project backers want funding from the World Bank and other international lending agencies which has so far not materialized.

This video is near the site of the proposed hydroelectric powerhouse. Downstream is the rapid called “Sweetness and Light.” Upstream is the section of the Karnali that would be drained.

Finally, a third proposal– which we represented during our expedition – is to keep the Karnali free-flowing as the only protected river in Nepal and a source of conservation, pride, and eco-tourism for the Nepali people. Nepal’s nascent river-protection movement – in part led by Megh Ale and his colleagues – has a unique voice in this controversy. They are a vibrant example of the diversity and uniqueness of Nepal’s many religious and ethnic groups, every bit as much a jewel as the river itself. Our expedition quickly learned that the Karnali River was not just a beautiful free-flowing river, but an ecological community that included a diverse and lively human element.

We paddled and floated through several small villages the first few days of the expedition. One memorable scene came as we approached a moderate-sized rapid around a large bend in the river – we saw a funeral pyre burning brightly on the bank with about 50 people surrounding it holding candles. The oncoming rapid required all of us to be paddling and so no one snapped a photo. While that picture remains only in our minds, many other eclectic cultural scenes were captured.

At the beginning of the trip, Megh told us we might see the “Raute” people, which are Nepal’s last nomadic tribe. Small bands of this tribe are known to live in the jungle surrounding the Karnali, though it is unknown where they live at any one time. On the fourth day of our expedition as we set up our tents on Scorpion Beach, we were greeted by two Raute who walked in out of the jungle to visit us. Their dialect overlapped with the Nepali language by about fifty percent, so Megh and the Nepali who were with us were able to talk with them.

Over the next twenty four hours, a few dozen Raute came into our camp, and then we went to their small nomadic village after hiking thirty minutes upstream. The band of Raute lived in small impermanent structures made of branches covered with tarps. They subsisted by cutting down large tuni trees whose rich dark wood they carved into bowls, boxes, and stools and then traded with Nepali villagers and occasional tourists. The Nepal government granted the Raute specific privileges to cut down the big and beautiful trees in the jungle, a privilege that was not without controversy because if regular Nepal villagers cut down the same trees, they would be fined huge sums of money. Our cultural exchange included us buying the hand-carved bowls for small sums of money, and the Raute chief getting a ride in one of our rafts, his first-ever such experience.

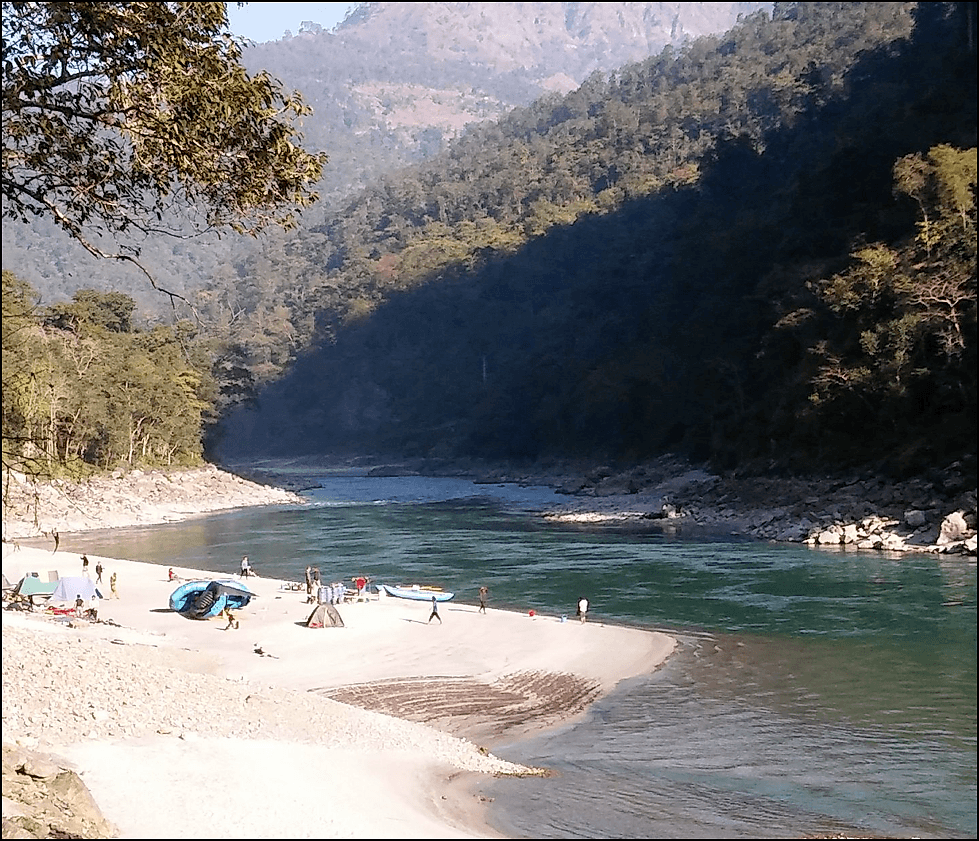

While the Raute provided the most unique of our cultural exchanges, we also had significant interaction with regular Nepali villagers who lived along the river. The Karnali is a wild and pristine river – with huge beautiful beaches lined with jungle forests – but every few miles a village was carved out of the jungle. The local people lived by farming rice and vegetables, fishing in the river, and selling and trading other goods by hiking out of the canyon up to roads. Several times on our expedition, we bought fish and vegetables from locals. At one point, we also bought a goat that was slaughtered and eaten over the next two days. The villagers were all friendly, and we often encountered them paddling along the edges of the river in long dugout canoes which they used to move people and products back and forth across the river in slower sections of water.

Our brightly colored expedition contrasted with the local villages both in style and in substance. Most of the villages farmed rice and had paddy terraces sloping down to the river. The stalks of the rice were stored in the branches of trees that looked a bit like truffula trees in Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax. We gawked at the views along the river, but at the same time I always felt a bit like we were also being gawked at. In fact, as we paddled in the river, and as we camped in the morning and evening, I felt like there were a hundred eyes on us at any one time. We occasionally saw people slipping through the jungle above us, sometimes walking down to the beach to say hello, other times not. Our expedition paddled along with the swift-moving river as we also moved through a human ecological community that had been thriving in this canyon jungle for hundreds of years.

While the human culture along the Karnali may be a few hundred years old, the river and the canyon geology has been at work for millions of years. A two-day stretch of the river runs through a steep-walled canyon of hard rock and creates fabulous rapids. We scouted and then raced through Class III and IV rapids named “Sweetness and Light,” “Jailhouse Rock,” “God’s House,” “Juicer,” “Flip and Strip,” and “Totali Ghat.” Although the proposed dam, tunnel, and powerhouse is upstream of this wild section of the river, the rapids would still be diminished by the hydropower project. What would be even more diminished would be the wonderful beaches – the dam would trap all of the sand and sediment and over time would rob and destroy the beaches in the lower river of their sand, just as dams do all over the planet.

Megh Ale has put together a band of activists in Nepal to address the threat of the Upper Karnali Dam and other threats to rivers across the country. This proposed dam, as well as others, would not only completely drain long stretches of rivers and block sand and sediment, it would also block the passage of migrating endangered fish. The Karnali already has at least two endangered fish including the mahseer, which can grow to five feet long and weigh over a hundred pounds, as well as the giant catfish which can grow even bigger.

The Upper Karnali Dam would further endanger these fish, the human culture that survives on the fish, as well as the burgeoning eco-tourist economy on the river. Three raft companies currently run a few multi-day expeditions on the river each year and there’s potential for many more. River activists believe the river should be protected for all of its economic benefits, including the eco-tourist trade. One of our crew mates, Ramesh Bhusal, who is a journalist and also works with the Waterkeeper Alliance on a different river in Nepal, believes the eco-tourist economy has great potential to provide more sustainable jobs than the hydropower project.

“The Karnali River is the most pristine river we have in all of the Himalayas, and is considered to be one of the best five rivers in the world for rafting and adventure.” — Megh Ale

Megh Ale takes the idea of protecting the river to an even larger scale. He foresees a “Karnali River National Park” that protects not only the river, but also a mile-wide corridor all the way along the river from Mt. Kailish on the Tibetan border, down into Bardia National Park in Nepal, and through Nepal into India to the headwaters of the Ganges. Megh’s visionary idea would be a first for the country which has many national parks and spends vast amounts of money every year protecting those parks and their endangered wildlife, but has zero protected rivers and nothing like America’s “Wild and Scenic River” program.

As our expedition ended, we floated out onto the plains at the town of Chisapani. The river widens and braids farther downstream, and although it remains undammed, large diversion structures suck some its water out for the massive rice farms out on the plains.

For now, the Karnali River is undammed, and the plans to keep it that way are also gaining steam. Efforts to reach out to the international funding agencies, media, and political leaders are continuing to move forward, as are efforts to further develop the eco-tourist economy of rafting and fishing. Nepal’s massive mountains are known throughout the world – what’s not known is that those massive mountains and their glaciers also produce some of the most beautiful rivers in the world.

The Karnali River is worth saving, and Megh and his team have dug in for the political as well as the wilderness adventure.

To learn more:

- Karnali River Waterkeeper

- Expedition details at Ultimate Descents

- Waterkeeper Alliance

- Nepal River Conservation Trust

******

Gary Wockner, PhD, is an award-winning international environmental activist, writer, and consultant who focuses on water and river protection. He is author of the 2016 book, River Warrior: Fighting to Protect the World’s Rivers. Web: GaryWockner.com

Gary Wockner, PhD, is an award-winning international environmental activist, writer, and consultant who focuses on water and river protection. He is author of the 2016 book, River Warrior: Fighting to Protect the World’s Rivers. Web: GaryWockner.com