It’s November 2015 and I’m walking along the streets of Old Town Cartagena, Colombia, just a couple blocks from the Caribbean Sea. It’s supposed to be the rainy season here where it rains almost every day, but it hasn’t rained for two months. Still, there’s a small amount of water running in the gutters in many of these Cartagena streets. I keep looking around to see where the water is coming from – people washing cars? Vendors washing off vegetables? Where is it coming from? It’s in almost every gutter on every street.

“Climate change,” says my colleague and guide for two days, Elizabeth Ramirez, who is a professor of environmental law and the Cartagena Baykeeper representing the International Waterkeeper Alliance in this port city.

“What?” I respond.

Elizabeth speaks in broken English, and I respond to her in even worse Spanish, but she finally explains, “Sea level rise. It doesn’t rain anymore, but the sea is rising up in the ground.”

When you think about sea level rise, you think about the sea rising up and coming over the beaches and rocks in storm surges, but here in Cartagena the rising sea has also increased the height of the groundwater under the city and the water is coming up through the gutters in the streets. This fact provides a cruel irony in Old Town Cartagena – the area is surrounded by a nearly 400 year-old 15-foot high stone wall which is an immense fortress designed to keep out invading armies. Now, the threat comes from underneath the city, an invader the Spanish colonials could have never imagined and from which the wall may do little to protect the city.

Sea levels have been rising in the Caribbean and Cartagena at a rate of about 1 inch per 10 years. Storm surges have occasionally already swamped small sections of the city that are very near sea level. Of further concern, scientists predict that sea level rise will be worse in the equatorial region of the planet, putting much of the Caribbean at risk including Cartagena and all around the Gulf of Mexico.

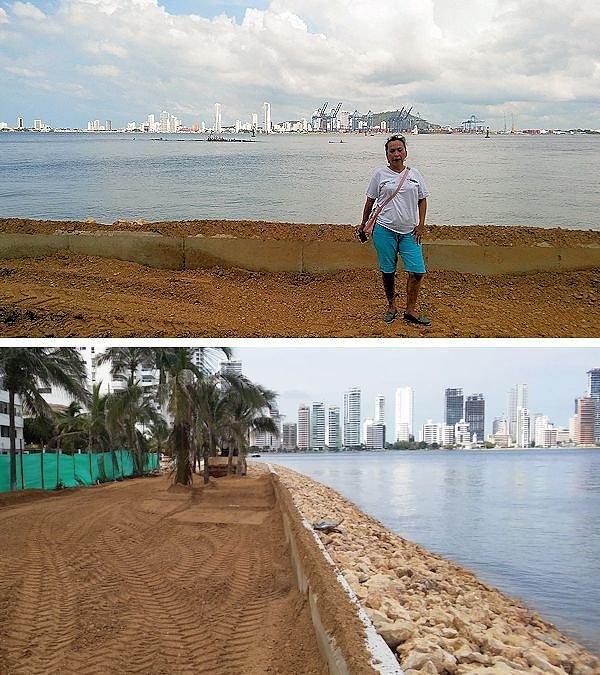

The City of Cartagena has been grappling with the sea level rise problem for at least a decade. In the glitzy touristy section of town – which is called Boca Grande, just south of Old Town – the City is building a 3-foot high retaining wall to keep out the rising sea and Cartagena Bay. As Elizabeth and I drive around the tourist area, we stop to look at the retaining wall under construction – it seems too small to me, more like “underfunded hope” rather than a large-scale public-works project that this and other Caribbean cities will need to actually protect themselves from climate change. Again though, there’s a concern that the wall will only address part of the problem related to storm surges because the increasing groundwater levels are also making the streets and gutters wet in Boca Grande. As we drive around the hotels, water splashed under our tires though a drop of rain had not fallen in weeks.

Cartagena Bay is large, nearly 40 square miles, and as we motor-boat around it the next day, the immensity of the bay and the environmental problems flowing into and around it feel genuinely overwhelming. Cartagena is a growing and bustling Latin American port city with myriad pollution problems – pollution from the tourist industry, the large industrial port, and the growing population (much of which lives in extreme poverty) – in addition to the major issue of climate change. These problems are clearly visible in Cartagena Bay which used to be clear but is now a kind of murky green-brown color with visibility of only a foot or two.

Over the last few decades, a bustling international tourist economy has developed along the Caribbean coast in Cartagena. Dozens of high-rise hotels, international flights, and some glitzy restaurants cater to the tourist industry. Along with the tourists also comes pollution, most of it as water pollution from the hotels and their wastewater treatment facilities that fail to keep up with the growth. Like many growing Latin American cities, Cartagena has fairly good environmental laws, but monitoring and enforcement of polluters is lagging and corruption is common. Over 15 years ago the World Bank targeted Cartagena with a grant to address the sewage problem, and the City of Cartagena continues to grapple with the growth in the tourist industry, but sewage problems persist in the bay, in the nearby Cienega de la Virgin, and in the Caribbean Sea along the beach.

The large and growing industrial port is also a significant polluter of Cartagena Bay. Oil, gas, bananas, and coffee beans (remember Juan Valdez?) are the largest exported products. Enormous chemical plants, fossil fuel powerplants, and container-ship terminals line much of the bay. The City of Cartagena and Colombian authorities struggle to regulate these polluters, some of which are immensely wealthy and powerful, including ExxonMobil. All along the bay as we boat along – and as we drove through the industrial section the day before – I see numerous ditches leading into the bay which are filled with garbage and muck often running within feet of massive oil tanks, chemical facilities, and other industrial carnage.

Amidst the bustling tourist and industrial activity lives a vast swath of people in extreme poverty, many living at subsistence level and feeding off of the fish in Cartagena Bay. A 2009 NPR report identified massive wealth disparities in the city, “misery malnourishment and disease,” and “raw sewage flowing down unpaved streets.” Another 2009 report in the Seattle Times, called it “Cartagena’s Hidden Shame,” where over 600,000 of the 1 million people in the city live in poverty, many in complete slums. As I traveled throughout the city and as we motor along the bay, I am struck by the poverty – mass numbers of people living in tin shacks, under bridges, or completely homeless. Garbage is absolutely everywhere – plastic bags and plastic bottles make up the most of it – and when it rains in Cartagena the garbage flowing into the bay makes it inhospitable.

The poverty of hundreds of thousands of people and the pollution is stunning. The juxtaposition of a wealthy tourist business and industrial port against this poverty is apparent everywhere. Subsistence fishermen paddle dilapidated canoes with makeshift paddles right in front of a huge multi-national corporate container port. Massive oil tankers motor through the bay making waves that slap up against tin shacks filled with children and families. Right across the bay from glitzy tourist hotels are thousands of shanties and slums, garbage hanging in the mangroves, and people living and feeding from the bay’s water which is filled with pollution.

Elizabeth Ramirez – the Cartagena Baykeeper – is a small, solid woman. She’s serious, and she needs to be. If you think the odds against you are a million to one, you might know how she feels. There’s not much support for environmentalists in Colombia or in Cartagena, the problems are immense and growing, and like environmental advocates everywhere she is understaffed and overburdened. But with the odds against her, she is steadfastly marshalling a team of colleagues to help move her mission of protecting the bay forward.

Elizabeth teaches and does research at three different universities in Cartagena, all three of which we visited to meet with her colleagues. With a law degree, a doctorate, and other specialist degrees hanging on her wall in her home-office of the Cartagena Baykeeper, Elizabeth is working to put together a coalition of scientists, policymakers, and students to create a campaign that monitors for pollution, enforces the environmental laws of Colombia, and organizes the local community to celebrate their watery heritage that surrounds Cartagena.

Specifically in 2016, Elizabeth is putting together a week-long series of events that will bring together Waterkeeper activists from around Latin America, focus a few days on the climate change problem, and then finish up with a multi-day “Cultural Festival of Water” along the bay and the Cienega to help galvanize the local community – rich and poor alike – to appreciate and protect Cartagena’s water. She’s even reached out to oil and chemical companies and is optimistic they will engage with the effort, for they too are vulnerable to climate change as their ports are threatened by the rising sea levels.

After our boat trip around Cartagena Bay, Elizabeth and her nephew drive me back to my hotel in Boca Grande. We communicate poorly due to our language difficulties, but I feel that I understand exactly what she has been telling me the last two days. “To protect the bay and the cienega, the people will need to be organized to help them celebrate their water culture,” she says to me. Elizabeth knows well that the problems of environmental degradation and social justice are completely intertwined in Cartagena, and that the solution must engage with the culture of people.

At less than five feet tall, Elizabeth Ramirez is barely taller than the cement wall the City is building to protect Cartagena Bay from climate change. She too seems like “underfunded hope” rather than the large-scale project needed to address the local environmental problems. But Elizabeth is driven – driven to protect the bay and organize her community to celebrate the watery world surrounding it.

********

Gary Wockner, PhD, is the Poudre Waterkeeper in Fort Collins, CO. He writes, travels, and advocates internationally to protect the environment. [email protected]