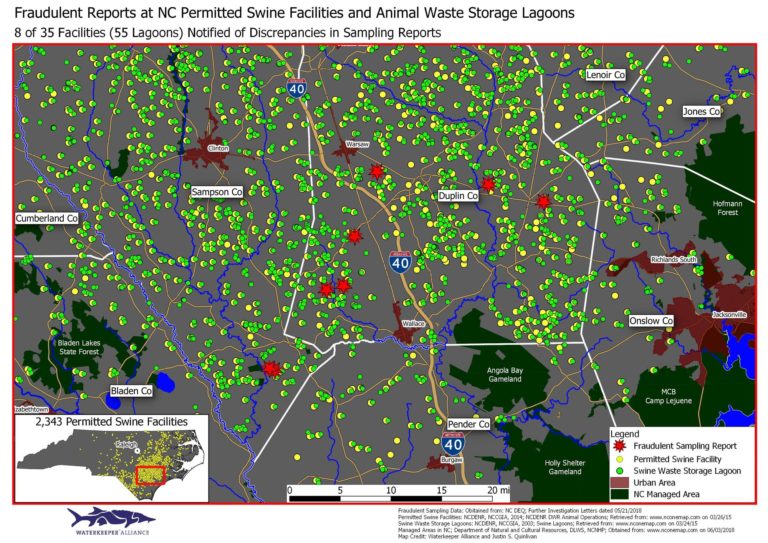

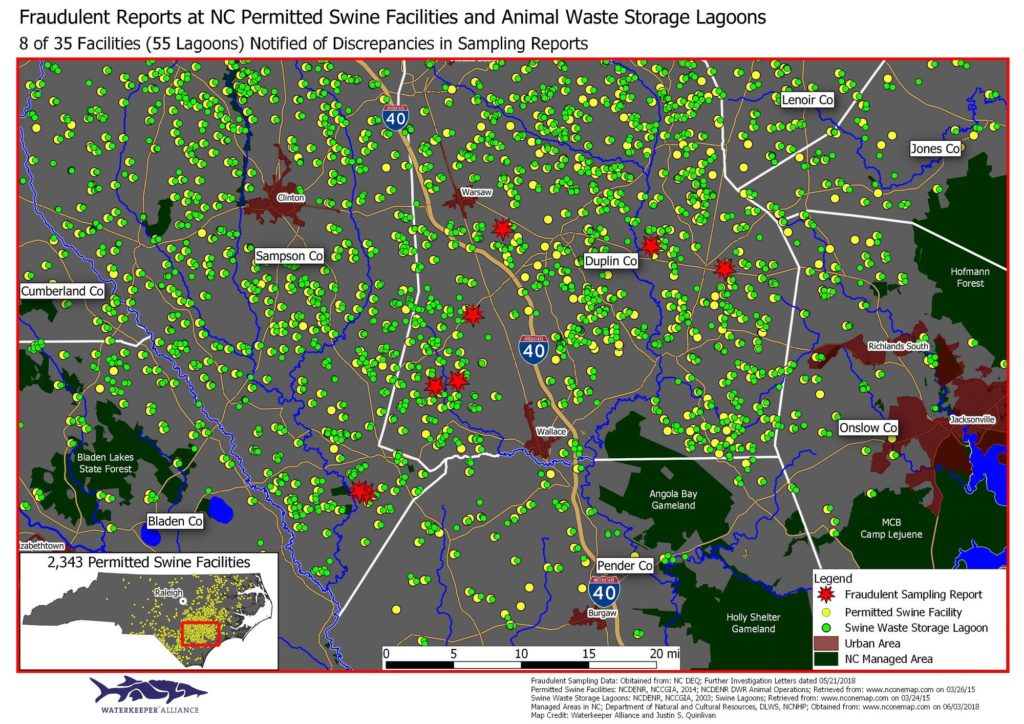

An investigation by two state agencies revealed efforts to cook the books and mislead regulators about the content of 55 waste lagoons at 35 hog operations in eastern North Carolina. The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) released 8 of the 35 letters mailed to operators as part of an ongoing investigation. These documents suggest problems with the industry, but also a troubling agency deference to operators and lack of concern about surrounding community members.

All of the facilities in question engage in industrial meat production and DEQ permits each of them to use the lagoon and sprayfield system to dispose of their enormous volumes of animal waste. The animals are housed over slatted floors where waste accumulates beneath them and is periodically flushed from the barns into an earthen pit (i.e., lagoon) and then sprayed, typically through industrial-sized sprinklers, onto sprayfields nearby.

The DEQ permits are supposed to prevent this waste management method from threatening nearby communities and waters with nutrient and heavy metal pollution. In fact, in 1997, when the NC legislature demanded that new or expanding operations use environmentally superior technology, the law required such technology to “substantially eliminate” the “nutrient and heavy metal contamination” associated with the lagoon and sprayfield system.

Preventing that threat requires monitoring and limiting waste disposal based on the concentration of various pollutants in the waste stream. The permit requires sampling of the waste, within 60 days of the start of spraying, for two nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus) and two heavy metals (zinc and copper). Spraying may be prohibited when nutrient or heavy metal levels in the sprayfields are too high.

The 35 facilities investigated had collected lagoon samples and sent them to the NC Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services laboratory in March. Lab technicians analyzed those samples and alerted DEQ staff in the Division of Water Resources (DWR). On Friday, April 13th, DEQ inspectors collected samples from all the facilities on the same day. The samples were sent back to the lab for analysis, and comparison of the results suggested serious problems evincing a widespread effort to defraud government regulators at the expense of public health and the environment.

The difference between the pollutant concentrations in the samples submitted by operators and those collected by DWR is astounding. Plant available nitrogen levels were, in most cases, much higher—as much as 291% in one lagoon—above those originally reported. Phosphorus levels varied, but at one lagoon, levels were 1182% higher than those originally reported. But the greatest discrepancy by far was found in the level of heavy metals reported. Each of the 8 facilities for which DWR provided records grossly underreported the levels of zinc and copper in their waste stream. The levels of zinc were misreported by as much as 101,108%. The difference in levels of copper was as great as 34,955%.

“This manipulation of data is an insult to the community members suffering from the industry’s continued use of the lagoon and sprayfield system. We demand real enforcement. The response to this slap in the face should be more than a slap on the wrist,” said Devon Hall, co-founder of the Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help (REACH).

Yet, despite this remarkable discrepancy, DWR appears more concerned about inconveniencing permittees than interested in evaluating the consequences of this fraud. North Carolina law allows DWR to inspect hog operations without advance notice, yet operators were alerted on Wednesday about inspections on Friday. Furthermore, the DWR letters “apologize for the short notice provided” and note steps taken to minimize permittee “disruption.” Naeema Muhammad, co-director of NCEJN asked, “Where was the letter apologizing to impacted community members? They’re the ones DEQ is supposed to protect from this industry.” Meanwhile, although the letters reference an ongoing investigation, DWR appears willing to leave quite a few stones unturned.

For instance, even though lagoon sampling can happen as many as 60 days after the start of spraying, DWR has not requested any land application records to determine how much waste was sprayed based on inaccurate lagoon sampling. Indeed, some of the letters do not ask for any records whatsoever and serve only to notify the permittee that an investigation is underway. Notably, by limiting its own investigation, DWR limits public knowledge about the problem, because records kept exclusively at the facility, including land application records, are not accessible via public records request. Moreover, DWR refuses the rest of the notification letters until the addressees confirm receipt.

This episode highlights various problems with the regulation of hog operations and its unsustainable method of swine waste disposal, including the reliance on self-monitoring. “It’s bad enough that profitable industry giants won’t invest in updated technology for their contract growers, but reliance on self-monitoring is especially dangerous given the continued use of the outdated lagoon and sprayfield system,” said Will Hendrick, a staff attorney with Waterkeeper Alliance. “The weak agency response suggests that our state government is more interested in coddling polluters than in protecting surrounding communities.”

Sadly, that industry deference is even more pronounced in the legislature, which last year passed, over the Governor’s veto, a law reducing nuisance recovery for victims of waste mismanagement by animal agriculture operations. As summarized by Kemp Burdette, Cape Fear Riverkeeper, “In the last month or so, we’ve seen a jury award $50M for harm caused by this industry, seen the State begin addressing the disproportionate impact of this industry on communities of color, and seen industry participants cook the books to get away with even more misdeeds. We’ve seen enough, and it’s time for our politicians to see the light and demand better waste management at swine operations.”