By Lee First, Twin Harbors Waterkeeper. Originally published by Twin Harbors Waterkeeper.

“What are we sacrificing by looking at the deep sea with dollar signs on the few tangible materials that we know are there? We haven’t begun to truly explore the ocean before we have started aiming to exploit it.” Sylvia Earle, Oceanographer

We know more about the moon and the surface of Mars than we know about the deep ocean. But increasing demand for rare metals and other valuable minerals could bring industrial-scale prospectors to seafloors off the Western U.S. before the consequences of ocean mining, let alone the nature of the ocean itself, are barely understood.

Seabed mining (SBM) is an emerging type of mining for minerals and rare earth metals on the ocean floor. SBM could help meet humanity’s insatiable thirst for essential minerals and theoretically power a “greener” economy. But these mining activities also carry a high risk for marine life and our ocean ecosystems, and threaten nearshore waters like the three-mile band of the Pacific Ocean managed by the states of California and Washington. SBM has been banned in Oregon’s state waters.

SBM will almost certainly cause major problems to our oceans, and the timing couldn’t be worse. The ocean, especially the nearshore ocean, is already facing a mixture of stressors: industrialization, climate change, ocean acidification and other forces which will increasingly challenge our ability to understand and co-exist with a healthy ocean. It is increasingly worrisome that there is little left standing between the deep sea mining machines and the wonders of the deep ocean.

It’s important to clarify the difference between the zones where mining is proposed to take place. Deep sea mining (DSM) is primarily proposed extraction of manganese nodules, seafloor sulfides around hydrothermal vents, and semi-precious minerals. For this article, I’ll concentrate on the threats posed by sea bed mining (SBM) in Washington State’s coastal waters. State waters include the area between extreme low tide to 3 miles offshore. Minerals in this zone include mineral rich sands, semi-precious and precious minerals (gold, titanium) and phosphorite.

What minerals/metals are sought after?

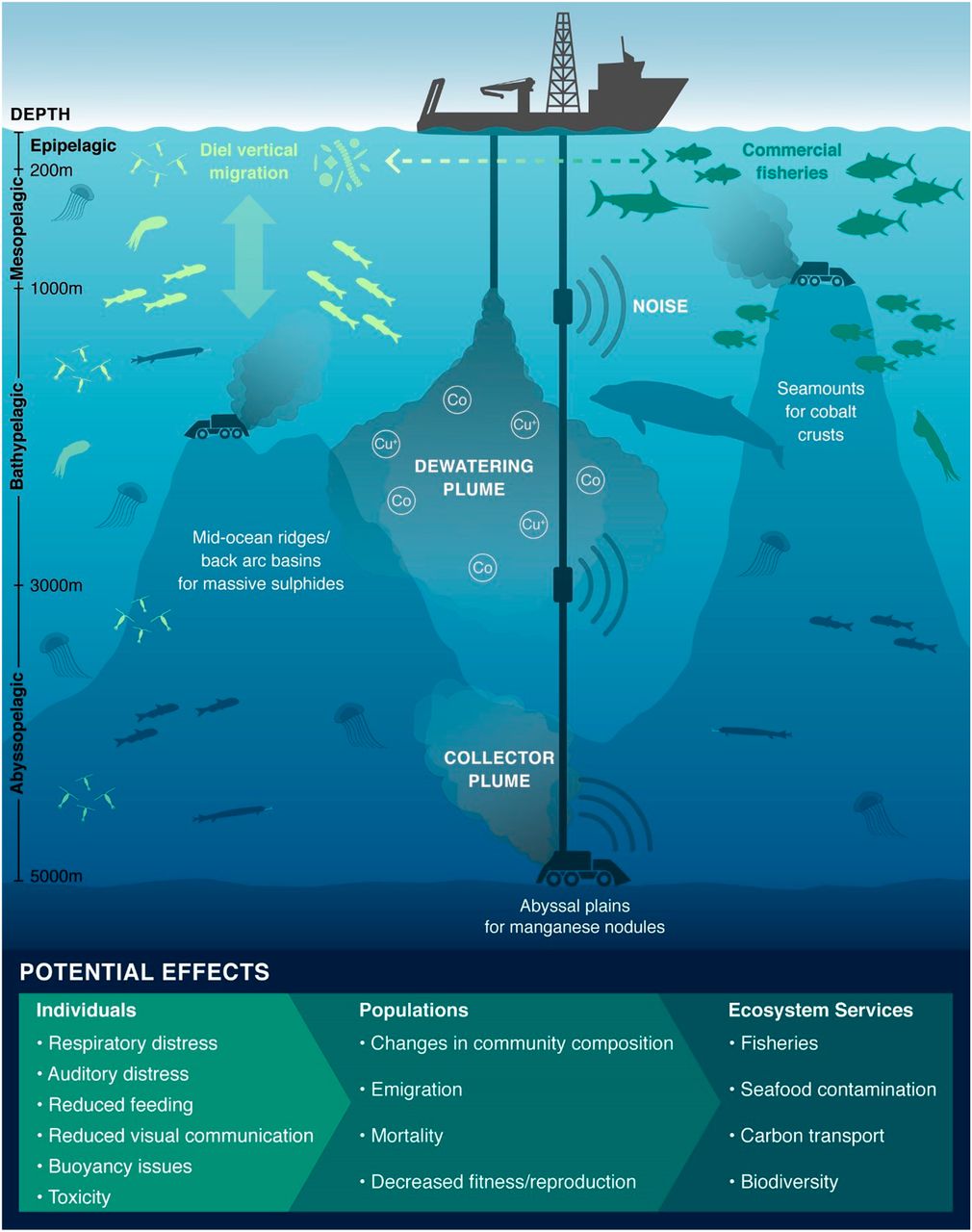

Gold, copper, manganese, cobalt, diamonds, zinc, and rare earth metals are some of the minerals found on and in the ocean floor. There has been a lot of press recently about the three major types of deep-sea mineral deposits of interest to proponents of seabed mining: massive seafloor sulfides around hydrothermal vents; polymetallic nodules on abyssal plains; and cobalt-rich crusts on seamounts. Most of the prospecting and mining planned for these mineral types at the moment is focused in international waters or in the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ’s) of other nations, but massive sulfides and seamount crusts are also found in the US EEZ. And there are other valuable minerals known to occur in the US EEZ or even in the waters within 3 miles of shore managed by the states including precious and semi-precious metals like gold, platinum, and titanium.

Many of the minerals found on the sea floor, such as erbium, europium, and yttrium, are deemed essential to the modern digital economy. Transition towards an electricity-based transportation and information infrastructure, especially in western societies, is increasing demands for precious and rare earth metals, powering our electric car batteries and electronics. There is increased interest in phosphorus nodule mining and phosphorite from the nearshore areas because phosphor-based artificial fertilizers are becoming more important to drive world food production.

Where is mining happening now, and under what authority?

The exploration and exploitation of High Seas mineral deposits is governed by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) under authority conferred by the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The ISA has issued 29 exploration leases so far. The leases were issued to contractors who work with the United Kingdom, China, France, Belgium, India, Germany, and Russia. About half of these contracts are for exploratory work in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, a submarine fracture zone in the Pacific Ocean. The rest are for explorations in the South West Indian Ridge, Central Indian Ridge, the Western Pacific Ocean, and the mid-Atlantic Ocean Ridge. The Lost City Hydrothermal Field, located in the middle of the Atlantic, is a hot-bed of the developing industry. It was discovered around the year 2000, and is jampacked with unusual life forms. There is some hard mineral mining in the US, for instance gold dredging off Alaska, but no real activity yet off the west coast. And close to home, mineral rich black sands have been documented along the lower Columbia River, Grays Harbor, and other coastal areas. There are serious concerns that global phosphorus deposits, which are an essential component of fertilizer, may eventually be depleted. It is found in many coastal zone areas on the west coast of the United States.

Major mining companies exploring SBM include Bluewater, Chatham Rock Phosphate LTD; De Beers Marine, South Africa; Diamond Fields International; Dredging International/DEME Group, Belgium; Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation, Japan.

What is the impact?

Oceanographer Sylvia Earle likens seabed mining to clearcutting forests. Mining, whether on earth or on the sea floor, is a short-term non-renewable activity. On earth and sea, once the minerals have been extracted, the resources and jobs are gone, and a highly damaged landscape is the result. By contrast, if fisheries are managed sustainably, the food and job security they provide can last for generations.

As with land mining, the impacts of seabed mining are very likely catastrophic. The main way to collect minerals is to “vacuum” the sea floor using heavy, high-tech dredging equipment. This equipment is noisy and can release harmful effluent. It has the potential to stir up sediments, block surface sunlight, and destroy aquatic life. Sediment plumes and waste discharge from mining could upset phytoplankton blooms at the sea’s surface, and introduce toxic metals into marine food chains.

Noise pollution that could change the swimming and schooling behavior of tuna, and cause dolphins and whales to strand. Areas where mining is being pursued are habitat for turtles, whales, fish, as well as serving as waypoints for migrating species. Some of these areas are already off-limits to deep trawling because of documented declines in diversity. Along with environmental groups, representatives from the fishing industry are warning of severe risks to ocean fisheries posed by SBM. In Washington State, mining in nearshore areas has the potential to be in direct conflict with recreational activities (beachgoing, whale watching, swimming, paddling, fishing, surfing, diving).

SBM could also exacerbate climate change even more by releasing carbon stored in deep sea sediments, which are known to be a long-term storage system for “blue carbon.”

SBM may be among the largest transformations that humans have ever proposed to the surface of the planet. While the annual worldwide land mine production of rare earth metals currently stands at around 100,000 tons, the deep sea floor is estimated to contain 15 million tons of rare earth oxides.

Let’s stop SBM off the coast of Washington

Oregon prohibited seabed mining for hard minerals within three miles (state waters) of their coastline in 1991. California and Washington should act now to follow that example given the significant emerging evidence that seabed mining would harm fisheries, wildlife, and communities.

Please help us with our campaign to prohibit seabed mining off the coast of Washington before it can start. Our plan includes a combination of outreach and educational efforts directed at state agency officials and lawmakers to first determine the right procedural pathway to a prohibition, and then more of the same to make it happen. It will take a few years – but with your help, we can do it.

Take Action: Do you work for or own a business in Washington or know someone who does? Business owners can help by signing on to this business sign-on letter effort. Please share with your your network: http://bit.ly/Biz-Against-Seabed-Mining-WA

Feature image: Amanda Dillon