Who Is Waterkeeper: Nelson Brooke, Black Warrior Riverkeeper

By: Thomas Hynes

Nelson Brooke joined Black Warrior Riverkeeper in Alabama when a friend from elementary school asked if he could help run the nascent organization for five months. The friend was David Whiteside, who founded Black Warrior Riverkeeper and now serves as Tennessee Riverkeeper, and the five month request has since ballooned into twenty years on the job for Nelson, and counting.

In retrospect, Nelson was an obvious candidate for the role. He had a direct connection with the river. As a kid, he was very often outside, whether it was fishing, hunting or scouting, frequently on the Black Warrior River. An Eagle Scout, he had always envisioned doing some kind of work with the outdoors. So when the call came for this job, it wasn’t that hard of a decision to make.

“I was told that I would be able to patrol the river in a boat and be able to bust polluters,” says Nelson. “And that sounded awesome.”

Recalling those early days, Nelson recalls being involved in the “hard nose advocacy and litigation” right from the start. He remembers being handed a list of zip codes and NPS permits and was told to find out who was polluting and where. Ever since then, Black Warrior Riverkeeper has been focused on the worst issues facing the river in order to protect it.

“We seek out the bad actors and sue them unapologetically,” says Nelson.

Suffice to say, Nelson was a little wide eyed at the beginning of his tenure, trying to get his arms around the watershed and all its many stakeholders and nuances. Becoming adept at the role meant understanding the granularity of countless streams and permits, but also being a spokesperson for the river. Black Warrior Riverkeeper’s many successes over the last two decades would suggest that Nelson has had no problem learning on the job.

The Black Warrior River watershed covers 6,276 square miles and measures roughly 300 miles from top to bottom. It is one of only two river systems entirely within the state of Alabama. Its footprint looks just like, well, a footprint, a left one to be precise. It has over 16,000 miles of streams within, as well as three main tributaries.

In general, and maybe to the surprise of some, Alabama is an incredibly ecologically rich place. Their rivers and streams are the most biologically diverse in the country. There are more fish, snails, turtles, crayfish, and mussels than anywhere else in the country. There are 13 endangered species in the Black Warrior River, and there are 127 species of fish. Had the river not been dammed over a dozen times, it would be even more biodiverse than it is today.

“It’s amazing actually how much is still in the river system despite all the dams and pollution and alterations,” says Nelson. “But it’s not just our fish, animals and plants. We are also one of the most geologically diverse states in the country.”

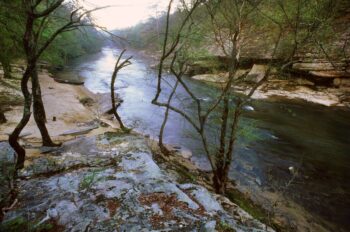

The watershed is also home to the first wilderness area created east of the Mississippi River. The Sipsey Wilderness has limestone canyons, waterfalls, spring fed crystal clear streams, old growth trees, and lots more. Nelson describes it as going back in time to what all the rivers used to be like.

“Alabama is a gem of richness in so many ways but most of what people hear about is our negatives. Even people who live here don’t know a lot of this stuff because the state of Alabama has done a terrible job of uplifting all of its positive attributes,” says Nelson. “So we see that as part of our job: highlighting all the problems and trying to clean it up for the sake of all this amazing stuff that we should not only be protecting but uplifting. If we focused on all our ecological natural attributes and made them available to Alabamians and visitors alike it could really fuel our economy in very significant ways.”

Instead the area has been a powerhouse for much dirtier work, including mining, logging, and other forms of heavy industry. There are numerous Superfund sites in the state, and, according to Nelson, a more places that could qualify. There are coal mines, coal power plants, as well as huge volumes of coal ash. There are also over 5,000 coal bed methane fracking wells. There’s a significant amount of unchecked agricultural runoff. Alabama also takes in out-of-state trash to be stored in landfills. There was even the infamous ‘poop train’ that shuttled down sewage from as far away as New York City to Nelson’s watershed.

“It literally created a big stink,” says Nelson. “Long story short, we had a huge amount of public outcry. We held a lot of hearings and got that practice stopped.”

Another major threat to Nelson’s watershed comes from the Alabama Department of Environmental Management because they don’t always enforce the law, going soft on polluters.

In one recent instance, Black Warrior Riverkeeper took on a massive coal mine that was proposed on 1,700 acres directly across the river from the city of Birmingham’s drinking water intake. Black Warrior Riverkeeper fought this battle for almost a decade and lost all their Clean Water Act permit appeals. However, they were able to pressure the University of Alabama, who owned land and mineral rights to the proposed site, to never get on board with the project. So even when Nelson and Black Warrior Riverkeeper lose in a court of law, they are often victorious in the court of public opinion.

Unsurprisingly, Black Warrior Riverkeeper has an in-house lawyer. Nelson knows their efforts are, at least, partially working because he hears the organization’s name dropped by regulators and lawyers throughout the state. Often they will say things like, ‘if you do this wrong, Black Warrior Riverkeeper will come after you.’ The legal strategy, both in-house and in partnership with outside counsel such as the Southern Environmental Law Center, has also helped inform the organization’s media strategy.

Or as Nelson says, “The media loves a fight.”

When Black Warrior Riverkeeper does win a case – which they often do – they work to keep that money in the community. They help craft supplemental environmental projects, engage local partners, and help reclaim and restore habitats. However, Nelson would love to see more done. Ideally, that would mean real protections and enforcement from government agencies.

“Going after polluter by polluter is the name of the game,” says Nelson.”But it’s not the most effective way to get the full systemic change we need to see a full recovery of the river.”

Clearly, Nelson has his work cut out for him if he’s going to see this transformation. Though given his track record, it doesn’t seem that far fetched.