Who Is Waterkeeper: Bruce Reznik, Los Angeles Waterkeeper

By: Thomas Hynes

Los Angeles Waterkeeper Bruce Reznik grew up in a quiet, residential area of Los Angeles County. As a kid, he can remember seeing signs pointing out the nearby Los Angeles River. He found it odd. He remembers thinking that Los Angeles must really have been starved and desperate for nature to call this concrete, channelized thing, full of dirty and polluted water, a river. He suspected that most other folks who lived along the river felt the same way, too.

The Los Angeles River, which originally served as the lifeblood for the Tataviam, Tongva and Kizh Nation for thousands of years, and still runs for nearly 51 miles through one of the most densely populated areas in the United States, is by no means hidden away. It’s not underground or diverted elsewhere. It’s right there, and yet in many ways, it is totally disconnected from its namesake city. All these years later, it is that feeling that motivates Bruce and reinforces his drive to work on the river’s recovery.

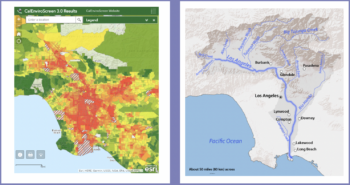

To be clear, Los Angeles Waterkeeper works on way more than just the river. Its jurisdiction is the entirety of LA County, which includes nearly 10 million inhabitants. (For scale, that’s about as many people as live in the entire state of North Carolina.) That is all to say there is plenty to keep Bruce and the team busy.

Recently, they helped pass Measure W, a voter-approved tax that raises about $280 million a year, in perpetuity, to better manage stormwater runoff. Perhaps their most noted accomplishment was a major settlement with the City of Los Angeles after a contentious 5-year legal battle, resulting in more than $2 billion invested to rehabilitate and monitor the city’s crumbling sewage system, and a 90% reduction in sewage spills over the past 2 decades. Their lawsuit against the State Water Board also drove the adoption of restoration plans, known as total maximum daily loads or TMDLs, for over 200 impaired waterbodies in the area, while they also just wrapped up three decades of overseeing a legal settlement against Caltrans that literally changed the way roads are built and maintained in California to address runoff pollution. In a region as massive as Los Angeles, these efforts entailed working with other nonprofits and community-based organizations throughout the county.

Nevertheless, a lot of time, energy, and attention inevitably flows back to the river.

“I am of the belief that you cannot get to a resilient and equitable Los Angeles, without a comprehensive plan for restoring the Los Angeles river. Whether the result of poor planning, racism or disinvestment, you have this phenomenon where the river has become the connective tissue of our most impacted and heavily burdened, frontline communities.”

Once the river became channelized, it became easier to build highways along the river and more heavy industry, which have all contributed to the view of the river as little more than a polluted flood control channel. It also became a pretty recognizable set piece for movies and television. Though it’s not exactly depicted as pastoral, but rather a venue for an illegal car race, like in Grease, or a daring chase scene, like in Terminator 2. Iconic, but not exactly a point of civic pride or community health.

A more crucial problem facing the river is that when it rains in Los Angeles, only about 10%-15% of that stormwater is captured upstream, which can pose significant flood risk to communities built far too close to the river’s banks. Unfortunately, it was what the river and its concrete channels were designed to do: quickly shuttle flood waters away to the sea. Bruce believes that significantly more stormwater could be captured in the upper watershed. This would both reduce the risk of flooding to downstream communities, while also allowing captured water to infiltrate and recharge LA’s abundant groundwater basins to reduce the need for so much imported water from the already depleted Colorado River, Bay-Delta and other sources. Much of this capture can be accomplished through green infrastructure solutions (also known as nature-based solutions), such as capturing stormwater under existing parks; creating new greenspaces at schools, homes and larger brownfield sites; or even creating new spreading grounds meant to capture large amounts of stormwater, which can also double as new community lakes and parkspace. Bruce acknowledges that these efforts may also require considering undesirable options like diversions, small dams and other things that “we usually don’t like”, but the overall benefits to the region could warrant such projects. Combined with pursuing opportunistic floodplain reclamation opportunities, such as converting unused train tracks, utility right-of-ways or abandoned industrial sites along the river to community greenways, we have the opportunity to simultaneously restore the river, make the region (which still imports 60% of its water for those 10 million residents) more water secure, and enhance community health and resilience.

“What I love about the Los Angeles River is its potential. It could be the jewel of Los Angeles, and the center of an equity and resilience strategy, but we’re not going to get there overnight. This is going to be a 50 year effort and cost billions of dollars,” says Bruce. “We are probably not going to be able to pull all of the concrete out of the river. But we need to figure out what is possible and make every effort to green as much of the river as possible. We owe that to river-adjacent communities and future generations of Angelenos.”

Bruce Reznik has been with Los Angeles Waterkeeper since 2015, but his roots in the movement go much further back. After graduating college and law school and several years working at a small consulting firm working on air quality issues, he took a job, a few miles south of his current jurisdiction, with San Diego Coastkeeper. After a decade plus working there, he tried a few other things, but eventually found himself back with Waterkeeper Alliance. He says what brought him back can be boiled down to one word: impact.

“Even as a young child, I always knew I wanted to do some sort of ‘do gooder’ advocacy. The Waterkeeper movement gave me the most potential to be effective and impact policy,” says Bruce. “And I want to be effective in whatever I do.”

Bruce credits Waterkeeper Alliance for building an organization that allows for that local impact while still being an effective global organization. He also credits the other Waterkeeper groups for making the movement strong and effective.

“The thing about the Waterkeeper movement is that we have local control, and we can reflect the communities in which we work. I love that local control. But being part of a global movement allows us to make change at a large scale and learn from one another. The connection, the conference, and the retreats is what really adds the most value,” says Bruce. “For all of the family-style dysfunction it can feel like with the Waterkeeper movement, in the end it’s still a family.”