What’s in your water: check before you swim

By: ajcarapella

By Will Hendrick, Waterkeeper Alliance senior attorney and manager, and Gray Jernigan, Green Riverkeeper. Photos by MountainTrue.

What’s in the water where you swim, boat, and fish?

There’s a gold standard for finding out, but, unfortunately, North Carolina isn’t using it. That has to change.

There are so many pathogens in our waters that sampling for each of them isn’t a practical possibility, so the Clean Water Act requires state environmental regulators to monitor for what’s called an indicator pathogen, one substance that indicates the potential for human infectious disease.

The state is also charged with determining how prevalent the indicator pathogen can be before a lake, river, or swimming hole is closed.

Testing for these pathogens does more than let swimmers know if the water is safe. It also lets them know if the water has been contaminated with livestock waste, a real possibility in a state in the top three nationally for poultry and swine production. It lets swimmers know if the water has been contaminated with human waste, a problem often associated with our aging sewage systems. The presence of bacteria such as E. coli and enterococci, which inhabit the intestinal tract of warm-blooded animals, is a direct indication of fecal contamination.

North Carolina is one of only 7 states that still uses fecal coliform as their indicator pathogen.

Our Division of Water Resources sets the standard for which pathogen is used as an indicator for fresh water, as well as a separate indicator pathogen for marine water. It also sets the standard for how prevalent pathogens can be before a swim area is closed.

What’s the best indicator pathogen for freshwater?

The Environmental Protection Agency conducted a series of studies in 1972 to better assess the relationship between gastrointestinal illnesses and swimming in sewage-contaminated waters. These studies demonstrated that E. coli are good predictors of gastrointestinal illnesses in fresh waters; while fecal coliforms are poor predictors of gastrointestinal illness.

EPA formally recommended in 1986 that E. coli or another pathogen, enterococci, replace fecal coliform bacteria in states’ water quality standards. North Carolina resisted making either change until federal law in 2002 forced the state to evaluate enterococci levels in coastal waters.

Unfortunately, North Carolina uses fecal coliform as its indicator pathogen when testing freshwater, as it has for decades.

In other words, we’ve known for nearly 50 years that basing recreational water quality standards on fecal coliform wasn’t in line with the best available science. But we’ve stuck with it anyway.

North Carolina is one of only 7 states that still uses fecal coliform as their indicator pathogen.

North Carolinians around the state often swim downstream from uncovered piles of poultry waste, cesspools full of hog waste, or dilapidated sewer systems. The most protective standard is a necessity for us.

The state already works hard to protect our coastal region. It monitors 204 sites along the coast, with increased monitoring frequency at many sites from April to September, and collects roughly 6,000 samples per year. Wouldn’t it be great if the state monitored our rivers for the benefit of recreational users as well. Just look at the number of tubers on the French Broad River in downtown Asheville on a hot summer day for an idea of how many people are getting out in our freshwater resources.

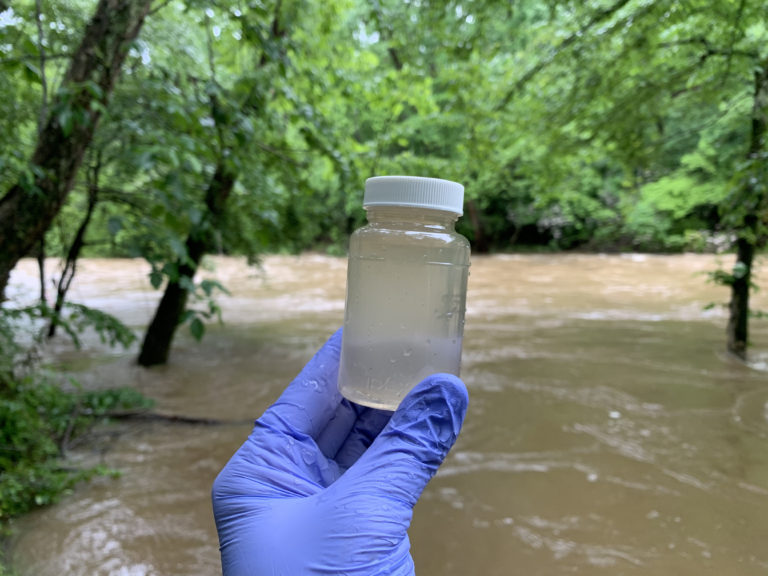

And while it would be laudable if the state were to put an equal effort into monitoring our freshwater swimming spots, Riverkeepers across the state are equipped to monitor E. coli levels. In fact, they’ll be doing so during the swim season and publishing results online.

The EPA has laid out a standard to ensure that waters available for public recreation aren’t burdened by levels of water pollution that could result in a hazard to public health. The state should adopt that standard.