UPDATE: Exposing Fields of Filth: Factory Farms Disproportionately Threaten Black, Latino, and Native American North Carolinians

By: Waterkeeper Alliance

By Sarah Graddy, EWG Communications Director; Ellen Simon, Waterkeeper Alliance Advocacy Writer; and Soren Rundquist, EWG Director of Spatial Analysis1

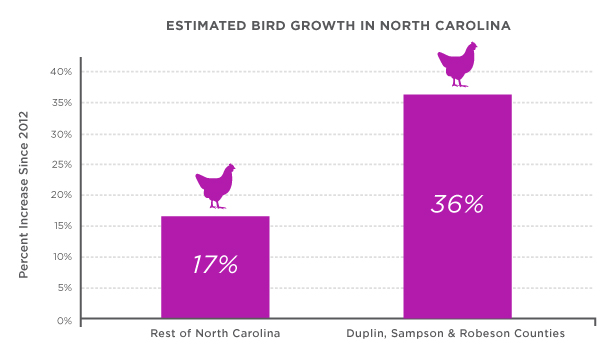

In the past eight years, three predominantly Black, Native American, and Latino counties in North Carolina – already home to most of the state’s industrial hog operations – added 30 million chickens and turkeys, according to a new geospatial analysis by the Environmental Working Group and Waterkeeper Alliance.

From 2012 to 2019, the estimated number of chickens and turkeys in Duplin, Sampson and Robeson counties swelled from 83 million to 113 million, a 36 percent increase. The three-county increase was driven by the astounding expansion in Robeson County, where the number of chickens and turkeys increased by 80 percent, to 24 million.

The Environmental Working Group and Waterkeeper Alliance estimate that in that same period, the number of poultry increased by 17 percent in the rest of the state, excluding those three counties. In total, the number of poultry in North Carolina, including those three counties, increased by more than 90 million birds, to a total of more than 538 million. Housed in over 4,800 operations, these chickens and turkeys have the potential to produce five million tons of waste a year.

That’s in addition to 8.7 million hogs generating 9.2 billion gallons of liquified waste and sludge a year. A 1997 state moratorium on new and expanded swine farms was made permanent in 2007 for farms that use so-called anaerobic waste lagoons – often-unlined pits of liquid manure and urine – as primary waste treatment.

Under current statute, any new or expanding swine farm must eliminate discharge into nearby waterways, and substantially reduce soil and groundwater pollution, ammonia emissions, odor, and pathogens. But no such restrictions have been placed on poultry operations.

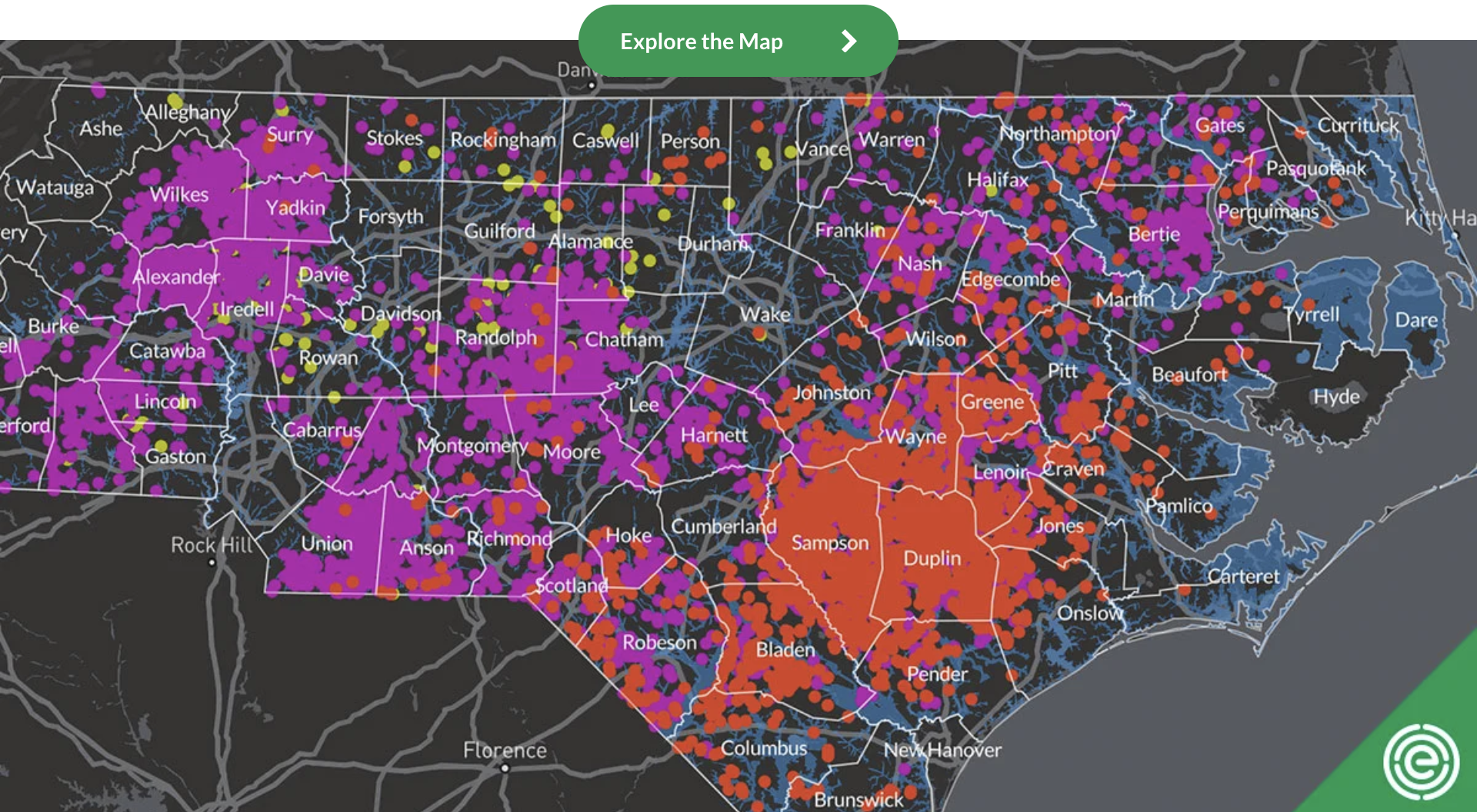

This interactive map, updated since originally published in December 2016, shows the approximate location of every industrial swine, cattle, and poultry feeding operation in North Carolina. Clicking on a location brings up details, including the number of animals and the estimated amount of waste each facility could generate in a year.

This graphic compares the percentage growth of poultry since 2012 in Duplin, Sampson and Robeson counties to that in the rest of the state.

In the 2010 U.S. census, 57 percent of residents of the three counties identified as Black, American Indian or Alaska Native, or one of several other non-white categories2 – almost twice the state average.

In the 2010 census, 38 percent of Robeson County residents identified as American Indian, the highest proportion of all counties in the state. Duplin County was nearly 21 percent Hispanic or Latino, the highest proportion in the state, and Sampson County had the third-greatest share of people who identify as Hispanic or Latino, about 17 percent. (People who identify as Hispanic or Latino can be of any race.)

The growing population of chickens and turkeys in the three counties could produce one million tons of waste each year – almost one-fifth of all estimated poultry waste statewide. That is 4,500 times the weight of the Statue of Liberty.

People in the three counties have long had to live with enormous quantities of animal waste and its stench, the threat to their water, and the impacts on their health.

The counties are home to 4.5 million hogs – more than half the state’s total. Raised in confinement – in facilities often referred to as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs – hogs in the three counties generate 4.4 billion gallons of liquified waste each year, enough combined urine and manure to fill 6,715 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The risks of living near North Carolina’s swine operations are disproportionately borne by Black, Native American and Latino people, something state officials have known for years.

In 2017, a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency review of a civil rights suit alleging discriminatory impacts of state permitting of hog operations found a “linear relationship between race/ethnicity [of residents within 3 miles of industrial hog operations] and…density of hogs.” The EPA expressed “deep concern about the possibility that African Americans, Latinos and Native Americans have been subjected to discrimination” as a result of how the state permitted hog operations. The suit was settled in 2018, with the state agreeing to stipulations that included a program of air and water monitoring near hog operations.

State law has held the number of hog operations relatively stable. Meanwhile, the state allowed the poultry industry to add one operation after another, with almost no regulatory oversight, in the same predominantly Black, Native American and Latino counties that were already most affected by hog operations.

None of North Carolina’s hog or poultry waste is treated. Waste from chickens and turkeys can legally be stored in uncovered piles for up to 15 days at a time. When it rains, waste from these piles can wash into nearby waterways. The waste is then trucked to cropland, where it is spread. The state does not require poultry operations to submit waste management plans, and environmental regulators are often unaware of where, when or how much waste is applied on fields.

Compared to poultry CAFOs, hog operations are better regulated. Swine CAFOs must have a state-issued permit to operate, but hog waste is stored in open, often unlined pits dug into the porous soil of Duplin, Sampson and Robeson counties, as well as neighboring counties in the state’s coastal plain that are vulnerable to hurricanes. An analysis by researchers from the University of Arizona and The Nature Conservancy of flooding from hurricanes Matthew and Florence found that 91 swine CAFOs and 36 poultry CAFOs were overcome by flood waters.

Living near North Carolina’s industrial meat operations means living with air, water and soil pollution. Research shows that living near its hog CAFOs also means having respiratory problems and a greater risk of death from serious diseases.

A 2018 Duke University study found that North Carolinians who live in areas dense with industrial swine operations have a higher rate of mortality from anemia; kidney disease; bacterial infection, or sepsis; and tuberculosis, as well as a higher rate of death and infant mortality, compared to other residents in the state. An earlier study reported that children in North Carolina who go to school near livestock operations have more wheezing and asthma.

A 2017 EWG geospatial analysis estimated that 160,000 North Carolina residents – including more than 24,000 residents of Duplin, Sampson and Robeson counties – lived within half a mile of a swine or poultry CAFO.

In practice, North Carolina requires little more than a building permit to open poultry operations housing up to 50,000 chickens or turkeys. Oversight of operations is almost non-existent, as EWG exposed in 2018. Most of the state’s poultry are raised in barns housing at least 35,000 tightly packed chickens. Some new operations have as many as 48 barns, housing up to 1.4 million birds in total at a time.

The disproportionate racial impact of the state’s regulatory abdication becomes even starker when counties are broken down into smaller census blocks, the smallest unit the census uses to sort demographic information.

For instance, since 2012, one 2.4-square-mile census block in Sampson County has seen three new industrial poultry operations built, which together can house more than 260,000 chickens in 12 barns. Of the 33 residents living within the census block, 85 percent are Black, and 97 percent are Black, Native American or other people of color.

EWG and Waterkeeper Alliance analysis found that, since 2012:

- In Duplin County, the estimated number of chickens and turkeys grew by about 11 million, a 31 percent increase.

- In Sampson County, the estimated number of chickens and turkeys grew by 7 million birds, or 24 percent.

- In Robeson County, the estimated number of chickens and turkeys grew by 24 million, or 80 percent.

- Altogether, this growth increased the estimated waste produced each year in the three counties by more than 260,000 tons.

Poultry Expansion Near Swine Facilities in Duplin County

Left before, right after. Source: the NC OneMap Geospatial Portal and Planet

Poultry Expansion Near Swine Facilities in Sampson County

Left before, right after. Source: the NC OneMap Geospatial Portal and Planet

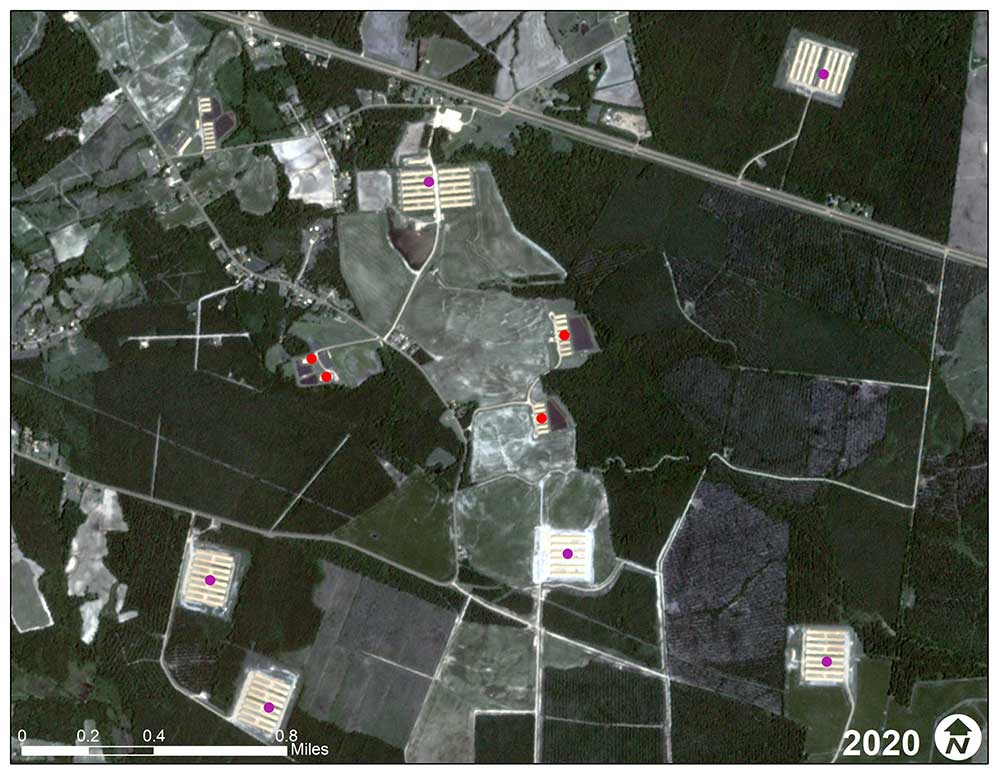

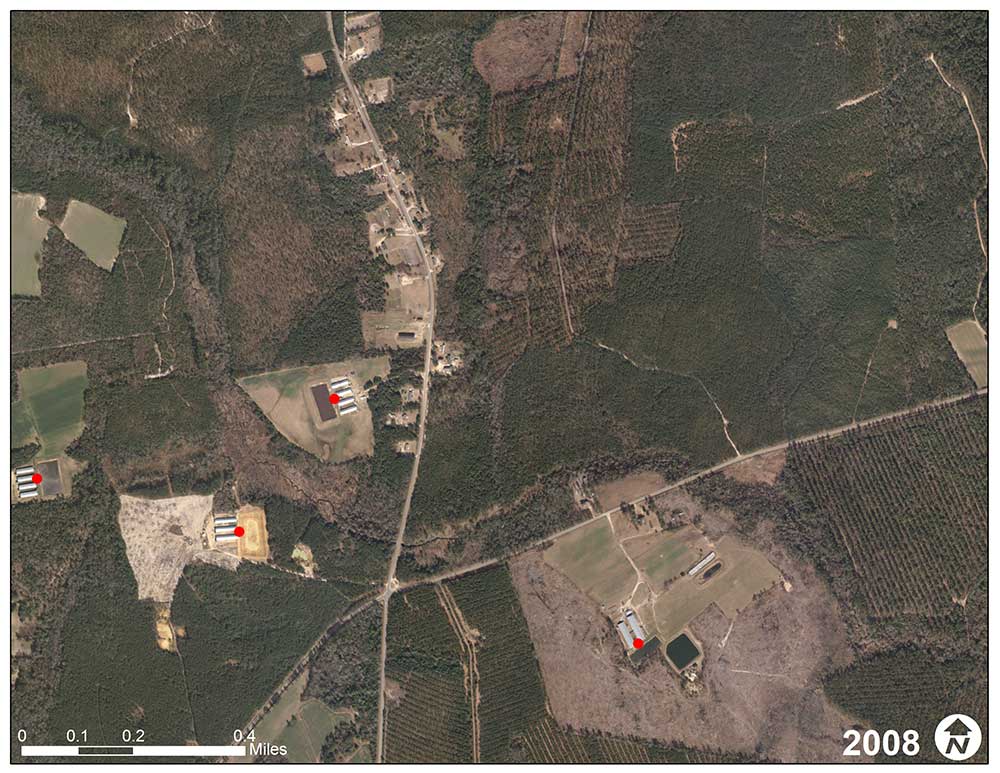

Poultry Expansion Near Swine Facilities in Robeson County

Left before, right after. Source: the NC OneMap Geospatial Portal and Planet

To protect the health of all of its residents, but especially those who already bear disproportionate burdens from industrial animal agriculture, North Carolina must address the rampant proliferation of poultry CAFOs. The state’s regulatory and legislative bodies must act to address the significant, increasing and unjust harm they have inflicted on North Carolina’s communities of color – particularly in Duplin, Sampson and Robeson counties.

State regulators must also rectify the longstanding lack of oversight of these operations, starting with studying where they are and how they’re managing their waste. The state should also forbid new operations from opening in flood-prone areas and do more to improve how poultry waste is managed.

To see the methods used in this study and detailed results, click here.

Footnotes

1 Employees of eight N.C. organizations conducted on-the-ground work verifying CAFO locations, essential to this report: Cape Fear River Watch, Catawba Riverkeeper Foundation, Coastal Carolina Riverwatch, Haw River Assembly, MountainTrue, Sound Rivers, Winyah Rivers Alliance, and Yadkin Riverkeeper.

2 Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; Some Other Race; or Two or More Races.