New Data Reveals N.C. Regulators Ignored Decade-Long Explosion of Poultry CAFOs

By Soren Rundquist, EWG Director of Spatial Analysis and Don Carr, EWG Senior Advisor¹

Although North Carolinians’ attention has rightly been focused on the state’s dense concentration of factory swine farms – concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, which produce 10 billion gallons of bacteria-laden, liquefied hog waste per year – the state’s poultry industry has grown dramatically with little notice.

Although North Carolinians’ attention has rightly been focused on the state’s dense concentration of factory swine farms – concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, which produce 10 billion gallons of bacteria-laden, liquefied hog waste per year – the state’s poultry industry has grown dramatically with little notice.

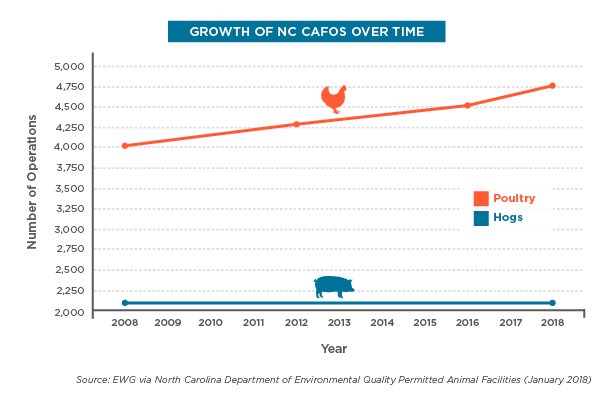

In a state long known for industrial hog production, new EWG research reveals there are now more than twice as many poultry CAFOs as swine operations in North Carolina.

The news is particularly relevant as state regulators debate the terms of the state permit regulating swine waste management. If you’re setting standards for pigs, you can’t ignore the enormous recent growth of the poultry industry that has largely flown under the radar.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, in 1997 there were 147 million birds in the state – egg-laying chickens, broiler chickens, and turkeys. Not coincidentally, 1997 was also the year when a moratorium on new hog facilities in North Carolina went into effect and the legislature ordered the state Department of Agriculture and Consumer Affairs to develop a plan to phase out anaerobic lagoons and spray fields as the primary methods of disposing of swine waste.

Fast forward to 2018. According to EWG’s recent analysis, poultry numbers leaped to 515.3 million animals, and swine lagoons still litter the state.

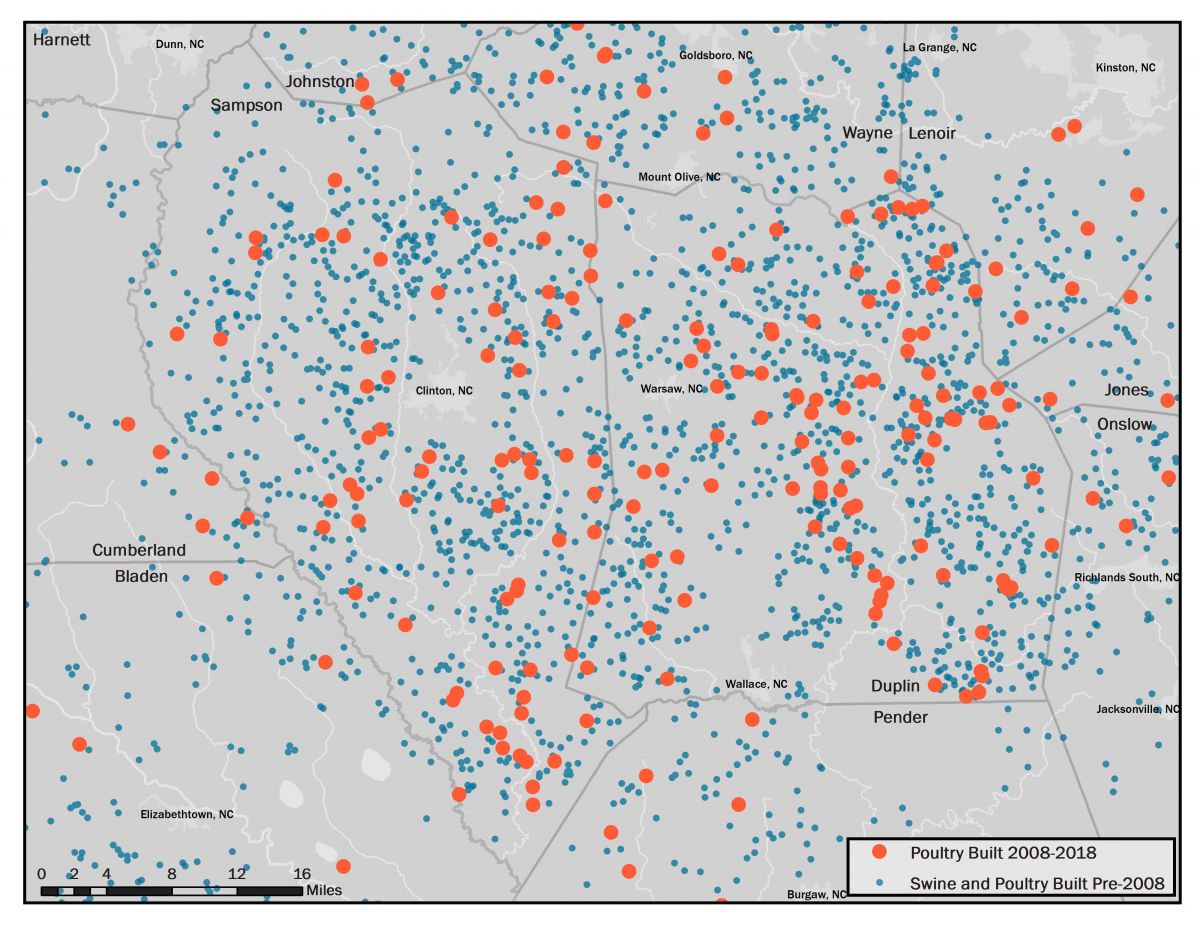

Our research shows that new poultry operations grew steadily across the state between 2008 and 2016, with more than 60 new operations added a year. The growth rate doubled between 2016 and 2018, with more than 120 operations added a year. In total, between 2008 to 2018, 735 new industrial-scale poultry farms were added.

The expansion of industrial-scale poultry operations on the coastal plain worsens the plight of residents already suffering from hundreds of swine operations. In the two counties that are home to almost half of all the swine operations in North Carolina, 82 million poultry are packed in between four million pigs.

Duplin and Sampson counties have historically been the epicenter of swine pollution, with 43 percent of all hog operations. As of 2018, they are the top two counties for poultry CAFOs, layering 762 poultry operations onto 931 existing hog operations. A staggering 23 percent of all new poultry operations tracked by EWG are located in these two counties.

And within the confines of Duplin and Sampson counties, factory farms are tightly clustered. An astonishing 93 percent of the poultry operations are within three miles of at least 20 other poultry or swine farms.

Poultry Operations Packed Into Sampson and Duplin Counties

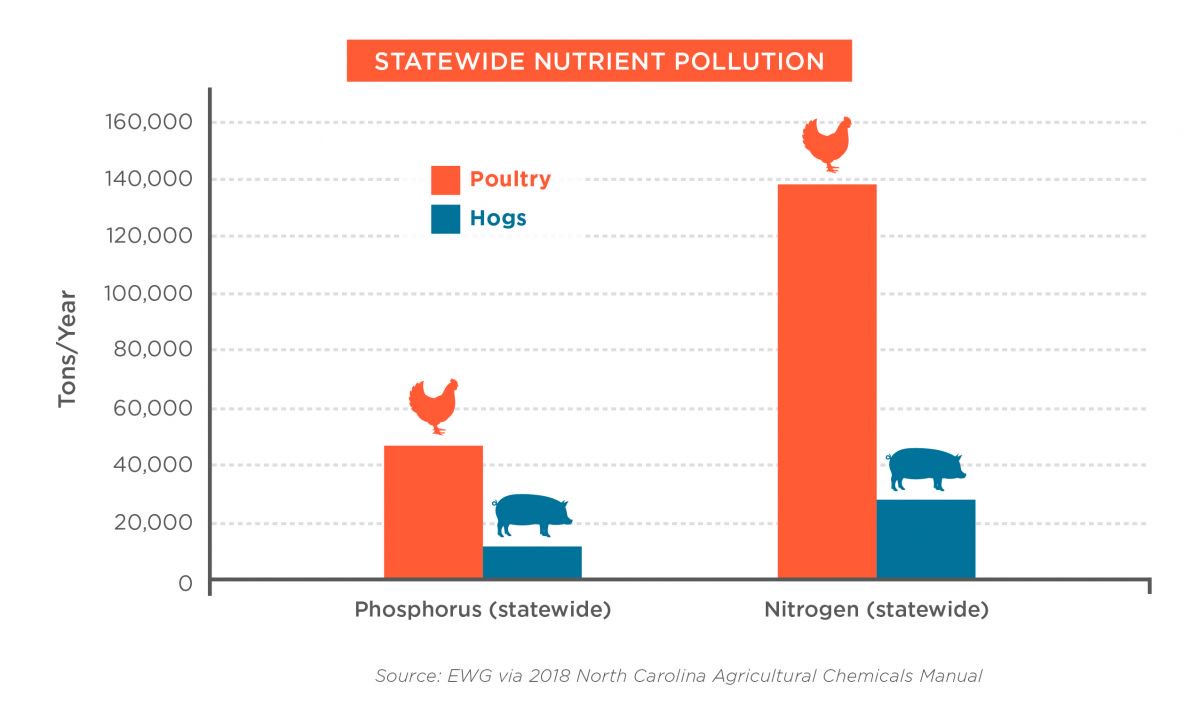

The rapid growth in North Carolina’s unregulated poultry sector means that across the state, poultry are now a bigger source of nutrient pollution than pigs.

North Carolina’s 4,700 poultry farms create five million tons of nutrient-laden poultry waste a year. That’s on top of the 2,100 swine operations, which generate enough liquified waste to fill more than 15,000 Olympic-size swimming pools every year. EWG‘s calculations show there is 4.8 times more nitrogen waste from poultry than from pigs and 4.1 times more phosphorous waste from poultry than from pigs.[2] EWG’s findings compare favorably with the Basinwide Manure Production Report prepared by the state’s Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ, that concluded poultry waste generated three times the nitrogen and six times the phosphorus as pigs in 2014.

The vast majority of poultry operations in the state do not require a permit and operate with impunity. Although the 1997 moratorium on new and expanded hog facilities in North Carolina was precipitated by hurricanes hammering farms in floodplains, 74 poultry operations have been built in the vulnerable area densely concentrated around three rivers – the Lumber, the Neuse and the northeastern area of the Cape Fear. Seven of those operations are new since Hurricane Matthew. After Hurricane Florence, an EWG and Waterkeeper Alliance investigation found that 35 poultry operations were flooded, 21 of which were actually outside the floodplain.

Poultry waste, which is mixed with feathers and bedding to form so-called dry litter and is then spread on fields, is kept in large piles, where rain can wash the nutrient-heavy pollution into nearby rivers. One of the few regulations on this waste is that it must not be left uncovered for more than 15 days. But these minimal regulations are rarely enforced, as DEQ does not inspect poultry operations unless there is a complaint. Worse yet, the water quality staff of the seven regional offices responsible for responding to complaints was slashed by 41 percent between 2011 and 2016 because of budget cuts.

As EWG’s new data and maps clearly show, there’s been an explosion of growth in the poultry sector that has largely flown under the radar.

The deluge of nutrient-saturated, biohazardous material churned out by North Carolina animal agriculture poses serious threats to public health. As such, the rampant growth in the state’s poultry industry must be factored in when state regulators meet in the coming days to renew the anemic general permit governing swine animal feeding operations.

NC regulators are required under state law to consider the cumulative impact of similar operations – hogs and poultry – on the environment because toxic runoff from both poultry and swine operations pollute the very same water bodies.

The issue of environmental justice is another reason regulators should factor the burgeoning poultry industry’s excessive pollution into their deliberations about the swine permit.

In January 2017, the U.S Environmental Protection Agency issued a stern letter to the North Carolina DEQ expressing “deep concern about the possibility that African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans have been subjected to discrimination as the result of NC DEQ’s operation of the Swine Waste General Permit program, including the 2014 renewal of the Swine Waste General Permit.” This echoed long-standing fears that factory farm waste disproportionally impacts minority communities.

Clearly, this recent and dramatic expansion of avian agribusiness and the threat these operations pose to the environment should be factored into regulators’ deliberations over the general swine permit. The DEQ must also press ahead quickly to complete its community mapping tool to ensure fair treatment of all citizens when permitting and regulating factory farms.

The health and well-being of North Carolina’s citizens hang in the balance.