This World Oceans Day, Pledge to #DefendTheDeep

By: Marc Yaggi

When the crew of Apollo 17 took their famous photograph of Earth in 1972 on the last crewed lunar mission, what was suddenly and dramatically clear to the entire world was that we live on a Blue Planet. More than half of the oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere comes from the ocean. Yet, we know very little more about this vast, magnificent world than we did at the time of the Apollo 17 mission almost a half-century ago. We have gone to the moon, we have our sights set on colonizing Mars, but more than 80 percent of the world’s oceans have yet to be mapped and explored. We don’t know nearly enough about this amazing resource that supplies much of the air we breathe, provides us with food, regulates our climate, and locks away carbon from our atmosphere.

We know even less about the deep sea, which is the planet’s largest habitat and is 99 percent unexplored. The parts of the deep sea we have explored reveal a myriad of exotic species, such as the very unique looking Anglerfish, which has its own headlamp unlike anything you’ve tried to buy at REI, the dumbo octopus, which, unlike most octopuses, doesn’t have an ink sac because it rarely encounters predators in the deep sea, and the aptly named yeti crab (Kiwa hirsuta) with its hairy claws. These creatures and others survive in an ecosystem of intense pressure and freezing temperatures. More species are being discovered all the time. At the same time, an untold thousands of species have yet to be discovered in the deep sea, and the value of this ecosystem is virtually unknown.

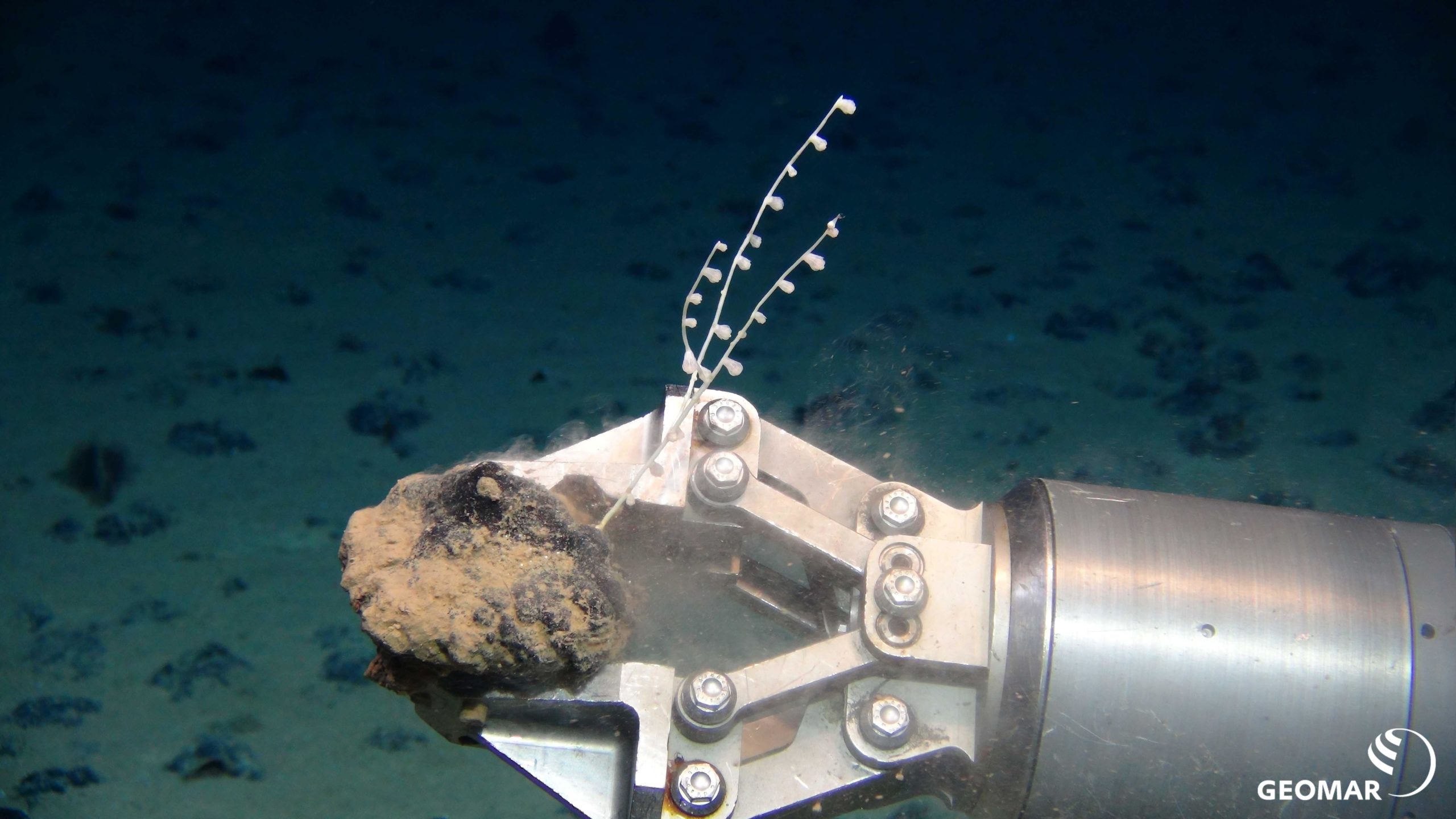

Just like the deep sea, chances are you haven’t heard much about Deep Seabed Mining, either. But pro-mining interests are working feverishly to launch the largest mining operation for minerals in history — more than 1.3 million square kilometers of the ocean floor. That is an area almost twice the size of Texas and located outside of any nation’s jurisdiction. These minerals are said to be critical to decarbonization and it is true that clean technologies are mineral intensive; however, those claims fail to account for other sources of minerals and breakthrough technologies like geothermal lithium.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) of the United Nations is tasked with governing and protecting the deep seabed, which is our public commons. However, ISA has issued 30 exploration contracts that are now awaiting permitting as ISA develops commercial exploitation regulations. Currently, it appears that none of the mining technologies being developed will result in “no serious harm.” In fact, potential impacts include, among other things, habitat loss, species extinction, noise pollution, light pollution, and disruption of carbon sequestration. These potential impacts and the lack of knowledge about the deep sea have recently prompted brands like BMW, Samsung, Google, and Volvo to support the call for a moratorium on Deep Seabed Mining.

We know extraordinarily little about the deep sea and the harm that would be caused by deep seabed mining, but we do know what harm has been caused by mining on land. We have destroyed mountain tops, filled in headwater streams, contaminated rivers, dirtied our air, depleted species, and denuded forests, among other atrocities. There is a real risk that deep seabed mining will permanently destroy the fragile deep sea ecosystem before we ever have a chance to study and understand it.

Rushing to mine the deep sea and gambling with our life support system is too big a risk. It is clear that the International Seabed Authority should place a moratorium on deep seabed mining until much more is known about potential impacts on this fragile ecosystem.