The Rio Grande Watershed is at its Ecological Breaking Point. Act to Preserve its Clean Water Act Protection

By: Rio Grande Waterkeeper

By Rio Grande Waterkeeper Jen Pelz

The Rio Grande, the third longest river in the U.S., begins as snowmelt in the high peaks of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains, then traverses 1,900 miles of desert and canyon before joining the waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

At least, it used to.

Unsustainable water use and climate change are drying up this once-mighty river. The year 2000 marked the first time in its history that the Rio Grande did not reach the Gulf of Mexico. It’s not uncommon now for less than one-fifth of its historic flows to reach the sea.

That makes a pending Trump administration proposal especially dangerous. The proposal could strip the river’s typically dry — but sometimes raging — washes, arroyos, creeks, and streams of Federal Clean Water Act protection.

The stakes are high: The Rio Grande provides irrigation and drinking water for more than 6 million people. And the river relies on every last drop of water that meanders its way from precipitation-fed streams, wetlands, and groundwater through the basin to its mother river and, ultimately, the sea.

These waterways crisscross the landscape like blood vessels, a vast hydrologic circulatory system that determines the health of the river itself.

Some of the waters in that circulatory system are thundering, like the Rio Chama, which is the Rio Grande’s largest New Mexico tributary.

Some are unassuming, like the Santa Fe River, which is often dry as it travels through the city of Santa Fe. Under the proposed rule change, the Santa Fe River could not only lose protection in its ephemeral reach, the portion of the river that does not flow year-round, but in its entire upstream watershed. The headwater-portion of that watershed is vital to ensuring the quality of the water for this community, as well as every other community living downstream.

Another waterway that could lose protection is the Rio Puerco. This little-known 140-mile-long wash of invasive salt cedar and cracked earth drains 7,000 square miles. It may only carry its sediment-laden chocolate-brown water for a few weeks a year, but it contributes 16 percent of the flows to the Rio Grande, and half its sediment.

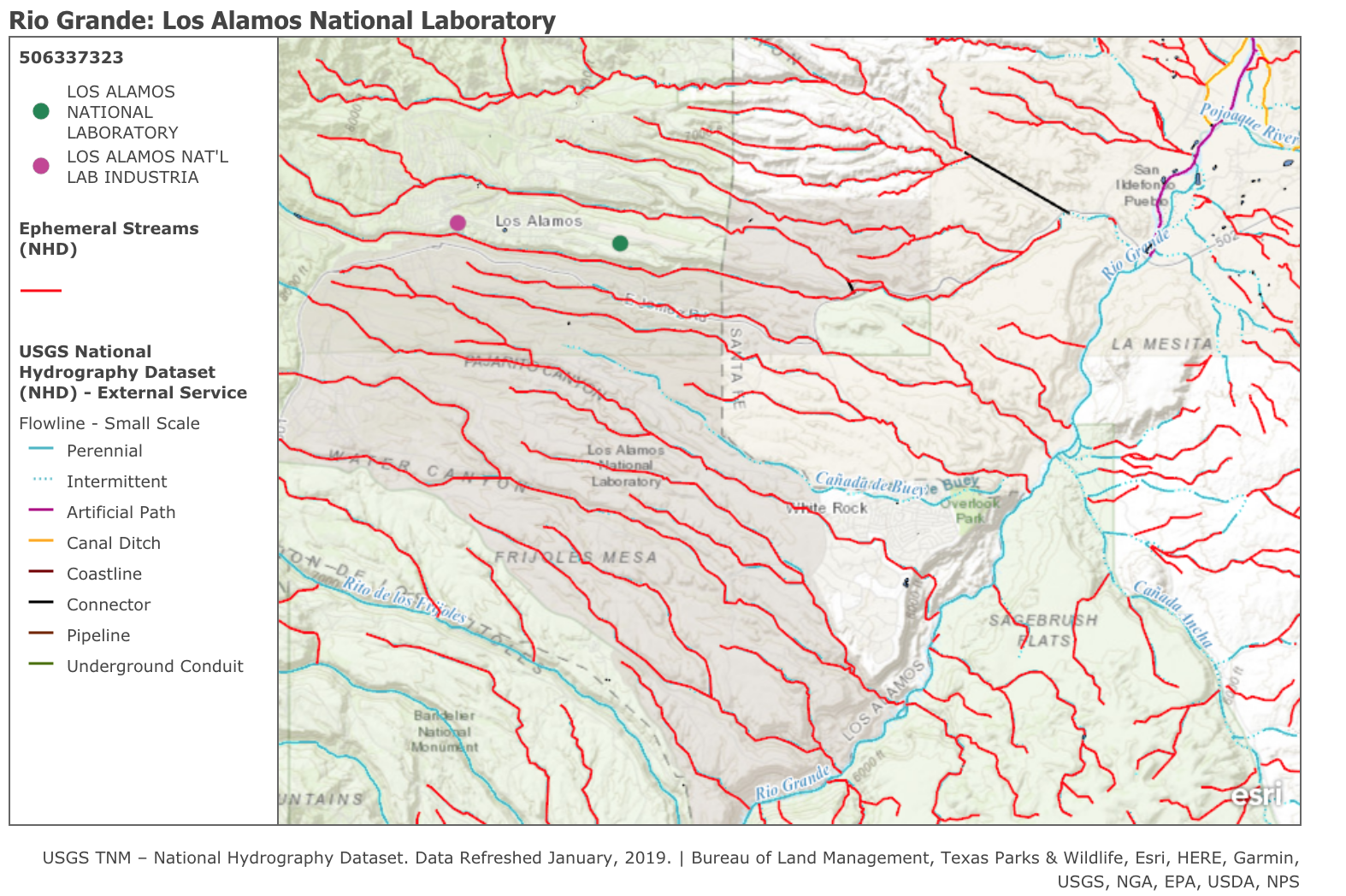

If precipitation-fed waterways were to lose protection, Los Alamos National Laboratory, which sits along a precipitation-fed stream classified as ephemeral in some federal data sets, could be free to discharge directly upstream from Santa Fe’s drinking water intake.

If closed-basin lakes and watersheds were to lose protections, the Central Closed Basin, a vast 14,605-square-mile closed-basin sub-watershed that begins near Albuquerque and stretches into Mexico, would lose protection. For a sense of its size, that sub-watershed is larger than the entire watershed for another of the nation’s iconic waterways, the Cape Fear River.

If the hundreds of miles of ditches and irrigation canals in the watershed lost protection, it would mean free reign for the already daunting number of polluters permitted to discharge into these ditches.

What’s more, the loss of Federal protections could hurt communities with ancient links to the river. The Rio Grande valley historically supported more than 100 Native American pueblos. The pueblo peoples, as well as Spanish and European settlers, used the fertile soil in the Rio’s floodplain to farm along its banks. They built a network of irrigation canals, called acequias, stretching from southern Colorado to northern and central New Mexico. Today, the Rio sustains 23 tribes and pueblos. While nearly half have their own water-quality standards, the rest depend on the same standards as the state of New Mexico, which in turn depend on application of the Clean Water Act.

Like only four other states, New Mexico doesn’t have authority under the Clean Water Act to regulate point-source dischargers; EPA retained that jurisdiction because New Mexico does not have the resources to effectively regulate these polluters. The tribes and pueblos don’t have those resources, either. Losing the Clean Water Act’s Federal protections for the state’s waterways would be a real, no-exaggeration, disaster.

It would be a disaster for a watershed along a central flyway that’s a critical migratory corridor for tens of thousands of sandhill cranes that overwinter in the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in central New Mexico, and migrate north each year through Colorado’s San Luis Valley to their breeding grounds.

It would be a disaster for the largest contiguous riverside cottonwood forest in the world, the Bosque, which flanks the banks of the Rio Grande from northern to southern New Mexico, and relies on the quality of both surface water and groundwater for its existence.

It would be a disaster for the wildlife — from bobcats, coyotes, and mountain lions to the reclusive New Mexico jumping mouse — that rely on this important riparian corridor.

And it would be a disaster for a river that’s already at its breaking point ecologically.

The average temperatures in the Rio Grande Basin increased by 0.7 degrees Fahrenheit per decade from 1971 to 2012, nearly double the global rate of temperature rise. Future mean annual temperatures in the Upper Rio Grande Basin are predicted to increase by 4 to 6 degrees Fahrenheit.

These higher temperatures mean increased demands and less water, which translates to drastically lower river flows.

By 2100, flows in the Rio Grande will decline in Colorado by 25 percent, in central New Mexico by 35 percent, and in southern New Mexico and Texas by more than 50 percent, according to Bureau of Reclamation’s West-Wide Climate Risk Assessment. These declines are Reclamation’s worst modeled flow outcomes from climate change in the entire United States.

Clean water in the Rio Grande and its network of tributary waterways is essential, because there’s so little of it. Without any excess, there is no dilution; if you destroy it at the source, it will have immediate irreversible impacts downstream.

Growing up in New Mexico, you learn quickly that water in the desert is magical. A thunderstorm can transform a desolate arroyo into a river. A swollen stream can awaken frogs from their slumber and create a new channel or wetland for birds and beaver. Groundwater can mysteriously rise to the surface creating a ciénega of life in an otherwise arid landscape.

As we think about what the future will be for this magical river and region, it’s essential that we keep the existing protections of the Clean Water Act intact.

You can help protect the magic of the Rio Grande by submitting comments about the Trump administration’s proposal to gut the Clean Water Act below. In the arid west, especially, every drop of water needs strong Federal protections. Raise your voice to defend our waters. #SaveTheCleanAct.