Protecting the Great Lakes at the Source

By: Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper

By Jill Jedlicka, Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper

The source, or headwaters, of a river or stream is the critical building block of waterways that influence the character and quality of downstream water systems. In a heavily industrialized region like ours and like many in the Great Lakes Basin, source water protection means preventing pollution from entering our waterways, or protecting the best of what is left. Larger waterbodies further downstream have suffered from legacy toxic pollution from industry and development. In Western New York, the upstream headwaters regions are still fairly pristine, and protecting them goes a long way toward our larger goal of clean water throughout the watershed.

Through our Headwaters Initiative at Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper, our goal is to protect the undeveloped headwater forests and wetlands that serve as a filter for drinking water flowing into Lake Erie, the Niagara River, and Lake Ontario. By preserving this critical acreage, the health of the entire region will be protected for future generations.

Headwaters protection for us means protecting a lot of our living infrastructure — standing forests, wetlands, riparian buffers, and the land that surrounds the headwater streams and wetlands so it’s not degraded, paved over, or disconnected ecologically from the rest of our watershed.

The greatest opportunities to preserve our fresh water are available where large areas of intact landscapes remain undisturbed – the headwaters. As this water travels downstream towards the Great Lakes, creating larger rivers and streams, it accumulates pollutants and encounters many barriers. Our strategy is to protect the areas where water is least-impacted first, to give it the best chance of maintaining its quality. We do that with lots of different tools, including, restoration projects, municipal education and engagement, and land conservation and acquisition.

While we’re not a land conservation organization, we do have the ability to acquire titles or easements for properties if that’s what it takes to get the conservation done, and we can do so with the help of a variety of partners.

We worked with The Nature Conservancy to buy a 222-acre forest at the headwaters of Eighteenmile Creek, one of Lake Erie’s major tributaries. By buying that forested land and its streams we were able to connect nearby, fragmented lands currently under protection. The resulting forest complex, at over 1,000 acres, serves an ecological function and creates community resiliency in the face of climate change. These forests generate and filter local drinking water and provide habitat for more than 150 species of birds, 30 species of trees, and 14 types of shrubs.

The land, which had been in the owner’s family for almost 100 years, consists of a mature mixed hardwood forest and intact floodplains overlying a glacial moraine aquifer that feeds a trout stream. Along the property, groundwater emerges from seeps along hillsides to create the headwaters of Eighteenmile Creek and provide drinking water to watershed residents.

Still, this is just a sliver of the sub-basin, which contains approximately 77,000 acres of land and 274 miles of streams. We want to do more to protect it. While less than 20 percent of the sub-basin’s riparian forests are currently protected, the headwater areas play an important role in shaping the downstream creek corridor and directly impact urban water quality.

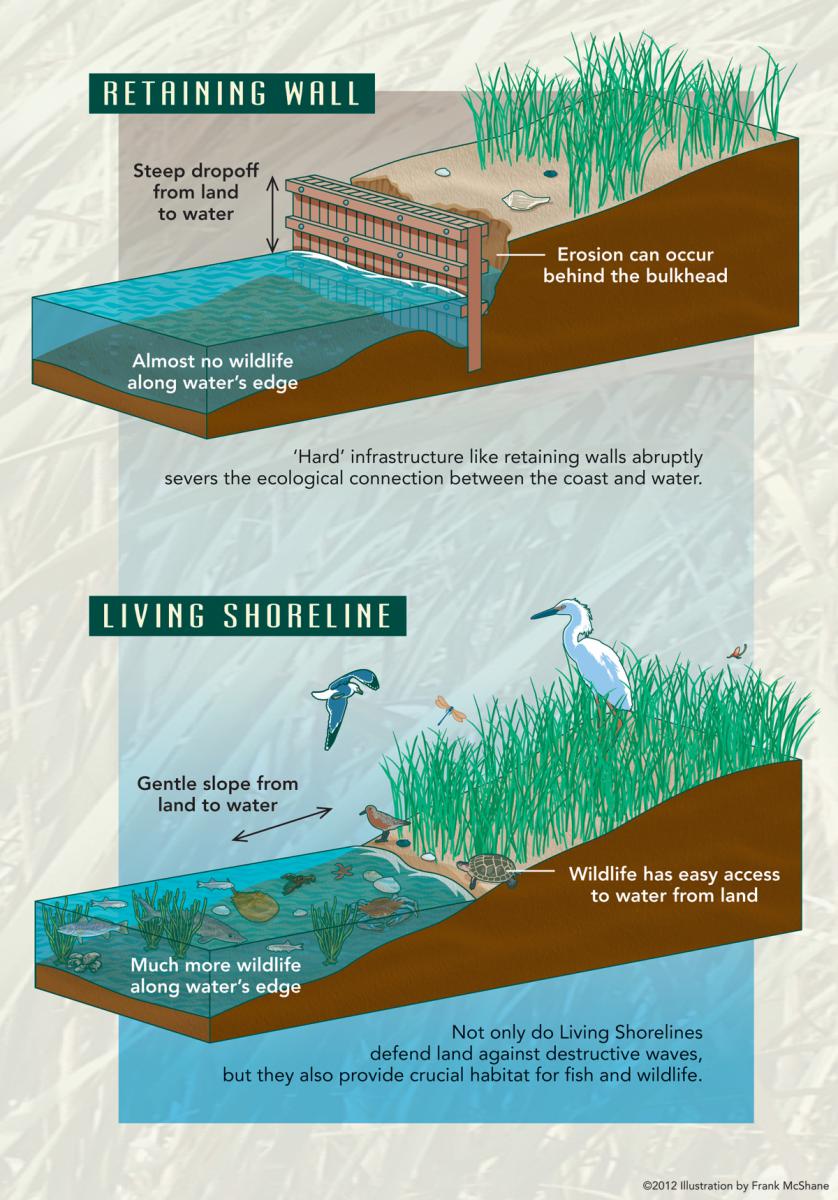

Another group of living infrastructure projects focuses on living shorelines. The current convention for managing waterfront properties uses hardened structures like bulkheads, with landowners mowing grass to the water’s edge. We take that hardened edge along land and water and erase it, adding native in-water vegetation and shoreline plants and trees to act as filters and buffers, while using natural materials such as stone, boulders, and log revetments, to buffer the shore and vegetation from storm impact and to create friendlier habitats for native wildlife.

These techniques can restore the ecosystem, and, in doing so, prevent erosion, improve water quality by absorbing pollutants and adding oxygen to the water, and provide critical resting, spawning, feeding, and nursery habitat for fish, amphibians, and perching areas for birds.

At one spot, we planted more than 1,300 native plants along the shoreline. Using boulders, logs, and vegetation, we built an in-water habitat for fish, crayfish, and aquatic insects that are an important part of the food web. We designed and installed nesting boxes to attract beneficial wildlife species, like the long-eared bat, songbirds, and wood ducks. In another three-year project completed this year on a Grand Island tributary, we installed 8,000 native trees and plants in addition to creating step-pools and regrading the shoreline. The creek happened to run through a golf course, and it was a cooperative effort to complete the restoration project in three years. It’s a great example of the kind of public/private/corporate collaboration we use to bring partners together for the benefit of our local ecosystem.

Projects like these serve as proofs of concept. By doing them, we demonstrate that they’re possible, that they’re beneficial, that they’re replicable. Building on these projects, and encouraging individual landowners and other groups to do likewise, is critical to protecting our source waters throughout the Great Lakes region.

The future of the Great Lakes depends on activists like you calling for drinkable, fishable, swimmable water for future generations. We need your voice to ensure that this vision for the lakes becomes a reality. Sign up here or below to get more information from the Great Lakes Waterkeepers and learn more about how you can take a stand for our Great Lakes!

This post was made possible thanks to funding from the Swarovski Foundation.