Protecting, Preserving, and Restoring the Floodplain

By: Matthew Starr

By Matthew Starr, Upper Neuse Riverkeeper. Originally published by Sound Rivers.

We still have more than a month left in the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, but, as it winds down, we need to start thinking about how we can be better prepared for the 2021 hurricane season, the 2022 season, and all the hurricane seasons in the years that will follow.

Rising seas and more frequent storms are expected to increase the areas of the United States at risk of floods by up to 45 percent by 2100, according to a Federal Emergency Management Agency study.

We’re going to be hit hard, by most projections. High tide flooding, defined as water levels of 1.6 to 2.1 feet above the average height of the highest tide, is projected to become a nearly daily occurrence by 2100, according to the North Carolina Climate Science Report. The same report found it is likely that the frequency and severity of inland flooding will increase as well.

How much that flooding increases in 80 years will be determined, in part, by what we do today. It will be determined by what we build, where we build it — and what we preserve.

Protecting, preserving, and restoring the floodplain is the cheapest and easiest way for North Carolina to protect its communities from hurricanes and flooding.

Investing in our natural infrastructure now — infrastructure like wetlands, forests, and swamps — will save us clean-up costs later. For instance, a one-acre wetland, one foot deep, can hold approximately 330,000 gallons of water. By some estimates, that 330,000 gallons is enough to flood 13 average-sized homes in thigh-deep water. The wetland you save today may save your house down the line.

But, unfortunately that isn’t how we’ve been thinking. Even as storms get worse and more frequent, North Carolina’s regulations often still only require sources of pollution, such as swine waste management systems, to withstand 25-year storms. As we all know, we’ve had two storms in the last five years that were, based on probability, 1,000-year storms.

We need to increase funding for programs that remove buildings from the floodplain.

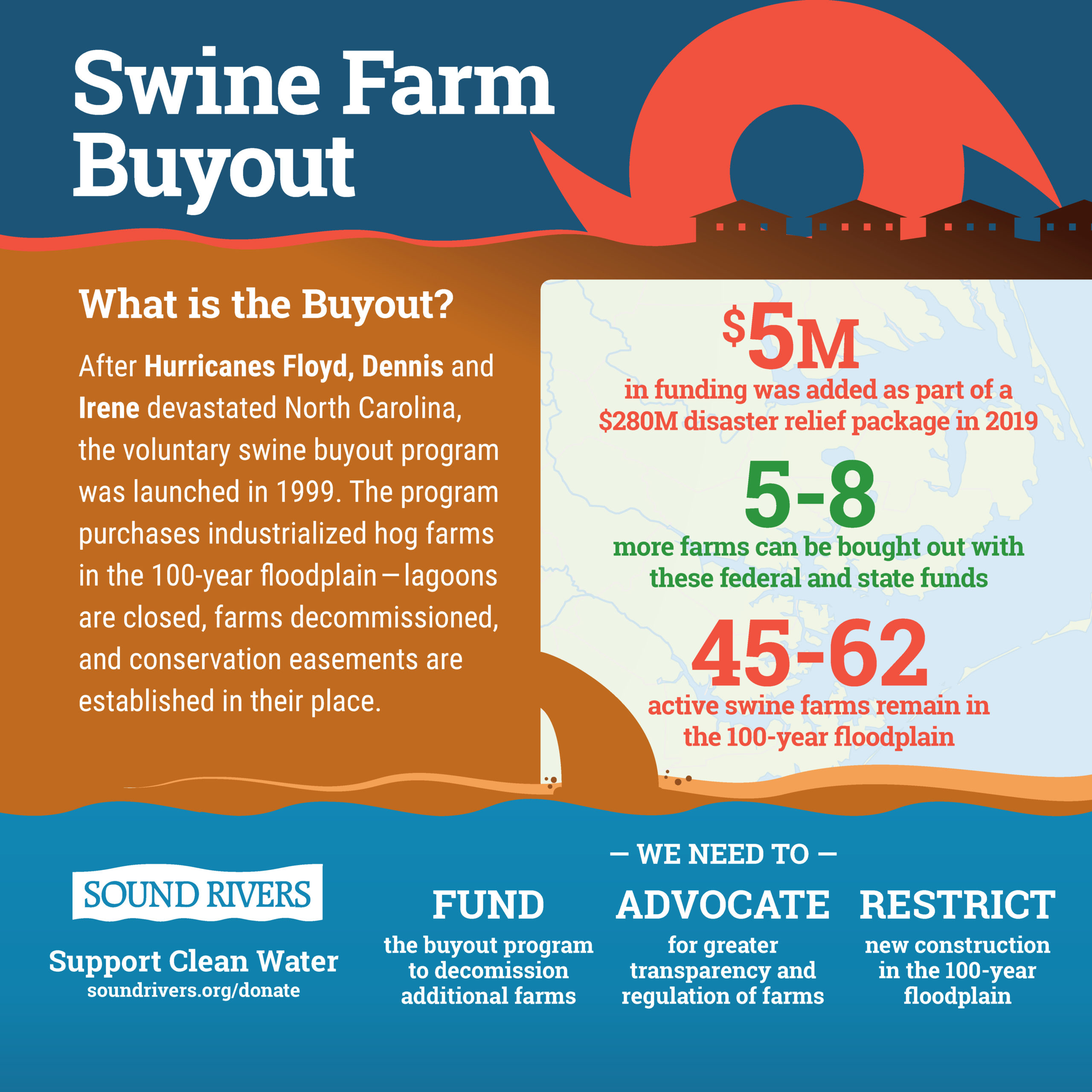

North Carolina’s floodplain is currently home to many of the state’s factory pork operations, which house nearly 9 million swine. After Hurricane Matthew my organization, Sound Rivers, was a co-applicant for federal funding for the swine fund buyout program. We need to buy out more operations, which keep millions of gallons of swine waste in open pits, so they’re not in the path of future hurricanes.

North Carolina’s floodplain is currently home to many of the state’s factory pork operations, which house nearly 9 million swine. After Hurricane Matthew my organization, Sound Rivers, was a co-applicant for federal funding for the swine fund buyout program. We need to buy out more operations, which keep millions of gallons of swine waste in open pits, so they’re not in the path of future hurricanes.

Our floodplains are also home to many of the state’s industrial poultry operations, as well as a variety of commercial buildings, and many wastewater treatment plants.

This needs to change. This is an urban and a rural problem. Even in the urban parts of the Neuse basin, there are still homes being built in the floodplain.

This has to stop. And we need to change some laws to make this happen.

For instance, poultry operations currently need little more than a building permit to open shop, no matter how flood-prone an area is. In flood-prone Robeson County, the population of chickens and turkeys increased by 80 percent between 2012 and 2019, reaching 24 million.

We know where that can go wrong. Hurricane Florence flooded operations that housed 3.4 million birds.

This industry is just one example. It’s clear we need stricter floodplain development regulations for all commercial and residential development, as well as keeping wastewater treatment plants out of flood prone areas. Building new poultry operations, which can house tens of thousands of birds and their waste in a floodplain is a health hazard. Building Crabtree Valley Mall on a floodplain has and been and will continue to be a financial hazard.

We can’t afford either.

Floodplain buyout and restoration is not only the cheapest form to mitigate flood impacts — it’s also the only permanent one. When a floodplain has no structures, there’s nothing to flood.

Being prepared for more frequent and severe storms in the coming years — and decades — means that we’ll have to shift our mindset.

We need to focus more on preparing for hurricanes and floods. Doing so is the only way we’ll be able to focus less on responding to them.

Feature image: Aerial shot of an industrial animal operation during Hurricane Matthew.