EWG and Waterkeeper Alliance: Poultry Factory Farms Disproportionately Threaten Black, Native American, and Latino People in North Carolina

By: Waterkeeper Alliance

113 Million Chickens and Turkeys in Three Eastern Counties Alone

The predominantly Black, Native American, and Latino residents of three eastern North Carolina counties now live with 30 million more chickens and turkeys than they did eight years ago, according to a new investigation by the Environmental Working Group and Waterkeeper Alliance.

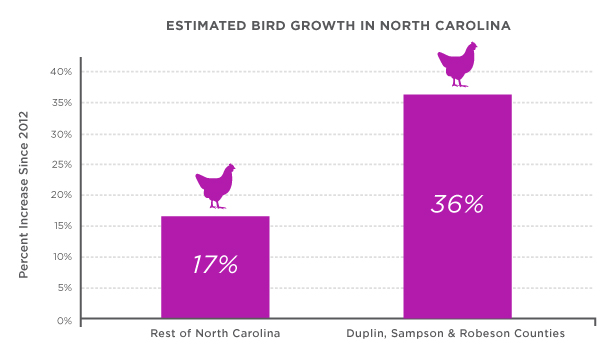

The groups’ report and map show that, from 2012 to 2019, the estimated number of chickens and turkeys in Duplin, Sampson and Robeson counties swelled from 83 million to 113 million, a 36 percent increase. This is more than twice the rate of growth in the state’s other 97 counties.

The growing population of chickens and turkeys in the three counties could produce one million tons of waste each year – almost a fifth of all estimated poultry waste statewide. That is 4,500 times the weight of the Statue of Liberty.

“North Carolina’s poultry industry is running amok,” said Soren Rundquist, EWG’s director of spatial analysis and one of the report’s authors. “The reckless growth of poultry operations, especially in the same three counties that already housed more than half of the swine in the entire state, is alarming.”

In the 2010 census, 57 percent of residents of the three counties identified as Black, American Indian or Alaska Native, or one of several other non-white categories – almost twice the state average. Thirty-eight percent of Robeson County residents identified as American Indian, the highest proportion in the state. Duplin County was nearly 21 percent Hispanic or Latino, the highest share in the state, and Sampson County was third, with about 17 percent.

“The unchecked growth of poultry operations in North Carolina comes with a steep cost for the state’s Black, Native American and Latino people,” said Will Hendrick, Waterkeeper Alliance senior attorney. “Yet state policy makers continue to abdicate their responsibility to manage the meat industry and its impacts on residents’ water, air and quality of life.”

The report’s interactive map, updated since its original publication in 2016, shows the location of every industrial swine and poultry operation in the state, with details about the number of animals and estimated amount of waste they could potentially produce each year.

Statewide, the number of chickens and turkeys increased by 90 million birds since 2012, meaning one in three of all birds added were in Duplin, Sampson or Robeson county. North Carolina’s more than 4,800 concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, now hold more than 538 million chickens and turkeys that could produce over 5 million tons of manure each year. That’s on top of 8.7 million hogs potentially generating 9.2 billion gallons of liquified waste and sludge a year.

None of North Carolina’s hog or poultry waste is treated. Poultry waste is stored in piles, and swine waste is often pumped into enormous open-air pits.

The state has known for years that the risks of living near swine CAFOs are disproportionately borne by Black, Native American, and Latino residents. In 2017, an Environmental Protection Agency review of a civil rights suit that alleged discriminatory impacts of state permitting of hog operations led the agency to express “deep concern” about discrimination against North Carolina’s African Americans, Native Americans, and Latinos.

The suit was settled in 2018, and the number of hog CAFOs has held roughly stable. Meanwhile, the state has allowed the poultry industry to add one operation after another, with almost no regulatory oversight, in the same counties already most affected by hog operations.

“The massive growth of poultry operations in the Lumber River Watershed over the last two years has been devastating,” said Jefferson Currie II, the Lumber Riverkeeper and a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, most of whom live in Robeson County. “All this is made worse by the fact that many of these CAFOs are in floodplains, putting vulnerable Native communities at even greater risk.”

Thousands of CAFOs are located in the state’s coastal plain, which is vulnerable to hurricanes and other severe storms. Numerous facilities were overcome by flood waters during and after hurricanes Matthew and Florence.