By Upper Neuse Riverkeeper Matthew Starr and Catawba Riverkeeper Sam Perkins

Scott Pruitt’s recent decisions to purge EPA’s Science Advisory Board (SAB), change eligibility requirements and appoint industry-friendly members are the latest indications that the agency established to protect our environment has been captured by the polluters it was created to regulate. SAB scientists are expected to draw on their expertise and review of scientific literature to inform EPA’s regulatory decisions. But Pruitt’s initial appointments to the SAB suggest an agenda driven more by industry directives than scientific rigor. In North Carolina, we’ve suffered the consequences of one recent SAB appointee’s environmental policy decisions that prioritized polluters over people.

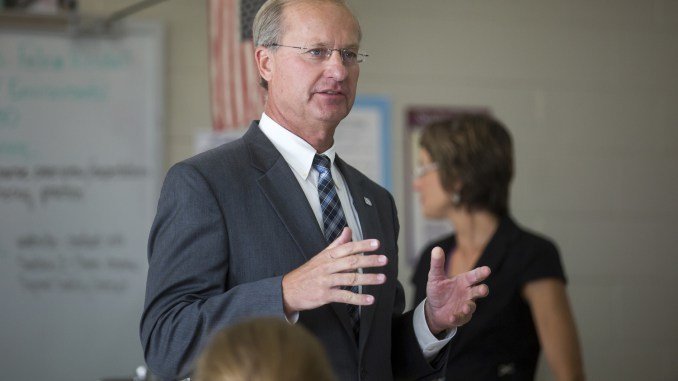

Donald Van der Vaart, tapped recently by Pruitt to join the SAB, led the NC Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) during a period of unprecedented coziness with regulated industries. More likely to dine with industry executives than hold them accountable, he eagerly advanced inaccurate industry talking points about the impacts of proposed regulations and led an administration marred by capitulations to regulated entities. He resigned from his position yesterday.

Van der Vaart repeatedly proved willing to ignore science at the behest of polluters. Rather than stop Duke Energy’s coal ash pollution, his agency ignored the state toxicologist, issued a series of conflicting statements regarding its impacts on drinking water, sought to eliminate state enforcement actions through a sweetheart settlement deal with Duke and even fought against court-ordered cleanups of coal ash at multiple facilities.

Van der Vaart’s willingness to overlook Duke’s pollution was consistent with a larger pattern of subservience to polluters under his administration. Mismanagement of untreated feces and urine by industrial meat production facilities is a threat to public health and the environment in North Carolina, and when Van der Vaart took the helm, DEQ had recently won a legal battle about the regulation of these operations. His team abruptly abandoned DEQ’s scientifically supported position, allowing an industrial poultry facility to continue operating without a permit. And when concerned citizens engaged in confidential negotiations with DEQ about hog waste pollution, Van der Vaart invited representatives of the pork industry to the table over citizen objections.

Ironically, Van der Vaart’s past appearances on the national stage suggest he opposes the very EPA regulations the SAB is supposed to inform. Despite scientific consensus regarding the need to address climate change, Van der Vaart’s DEQ sued to block the Clean Power Plan. He rejected years of scientific evaluation of the connectivity of water bodies when challenging EPA rulemaking designed to clarify the scope of the Clean Water Act. And just last fall, Van der Vaart penned a letter to President-elect Donald Trump that underscored his disdain for environmental regulation and, bafflingly, expressed concern that EPA had “become overly involved in environmental matters.”

As we’ve seen time and again, Van der Vaart finds it less objectionable when the agenda driving environmental regulation is set by polluters. In North Carolina, his DEQ became a bigger hurdle to cleaning up pollution than regulating the polluters themselves. Perhaps this deference to polluters is why Pruitt wanted him on the SAB in the first place?

Matthew Starr is the Upper Neuse Riverkeeper at Sound Rivers, a nonprofit organization that guards the health of North Carolina’s Neuse and Tar-Pamlico River Basins.

Sam Perkins is the Catawba Riverkeeper at Catawba Riverkeeper Foundation, a nonprofit organization that guards the health of the Catawba-Wateree River basin in North Carolina and South Carolina.

Photo by North State Journal