Haw Riverkeeper Emily Sutton is fighting the MVP Southgate pipeline in her North Carolina watershed, work that doubles as a master class in community organizing.

“She hasn’t let up, not one time,” said Kelly Bollinger, who, with her husband, Daniel, owns land in Green Level in Alamance County that was along the original planned path of the pipeline. “She believed the whole time that we could not just change the path of the pipeline but defeat this whole thing. I still believe that, too.”

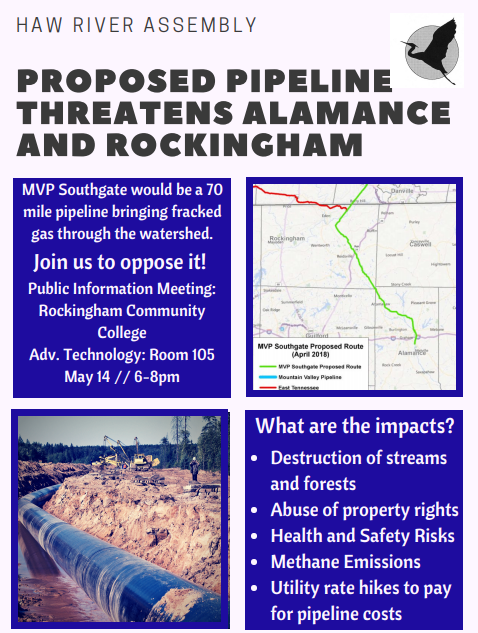

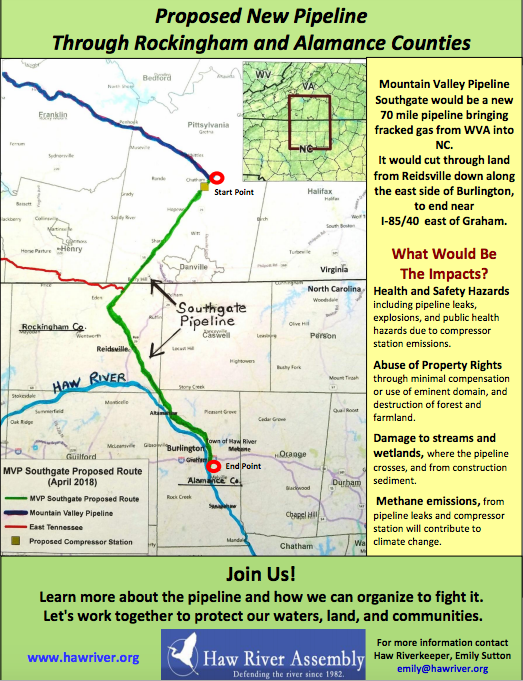

Sutton first heard about the pipeline proposal when she read an April report in NC Policy Watch. The piece included a 12-county map showing the pipeline would cut through the Haw River basin. Sutton did her own research, scouring MVP’s website and pulling from the extensive resources on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission on Delaware Riverkeeper Network’s website. Then she set up a community meeting, promoting it by putting fliers from her group, the Haw River Assembly, in grocery stores, coffee shops, libraries, churches, and schools and plastering it on social media.

About 50 people came to that meeting at a food co-op on April 25. Sutton proceeded carefully — and quietly.

Lesson one: When your group is together, create enough quiet so quiet people can speak.

“People are intimidated,” Sutton said. “If you are intentional about leaving that space for people to engage, they’ll take it. You just can’t talk through your questions. You have to give people enough space and quiet to participate, which is hard for a facilitator to do. You have to provide enough quiet time where it’s almost awkward.”

Four landowners came to the first meeting. All had gotten letters saying their property was along one of six proposed routes for the pipeline.

“We spoke up at the meeting; we had a lot of information they didn’t know anything about,” Daniel Bollinger said. “The land agent had already contacted us. They didn’t know it was this far.”

The Bollingers invited Sutton over to their house. She walked the land with them.

“We became pretty fast friends,” Sutton said. “I gave them as much information and talking points as I could for them to talk to their neighbors.”

Lesson two: People in the affected community know best how to approach their neighbors.

The Bollingers started reaching out to their neighbors about the pipeline, then they set up a Facebook page.

“I couldn’t go door to door and talk to people about how they should be fighting this pipeline,” Sutton said. “It was really Daniel and Kelly who talked to their neighbors, talked to their church, talked to their kids’ school groups about how they would be impacted.”

Lesson three: On-the-ground work is a great way to gather facts.

From those talks with neighbors, Sutton and the Bollingers figured out where the proposed route was, based on who had received letters telling them the pipeline might run through their property.

Sutton started planning meetings nearly every month about the proposal. Sometimes ten people came; in June, about 50 people gathered in the Bollinger’s barn to make handmade yard signs.

Lesson four: Grassroots organizing inspires unexpected help.

A volunteer artist, Jan Berger of Paperhand Puppet Intervention, designed beautiful yard signs, which sent people to the group’s website nomvpsouthgate.org, drawing new people to the movement.

Lesson five: Becoming an expert means new opportunities to recruit.

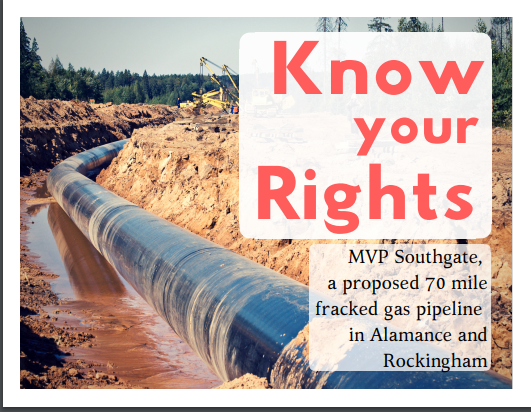

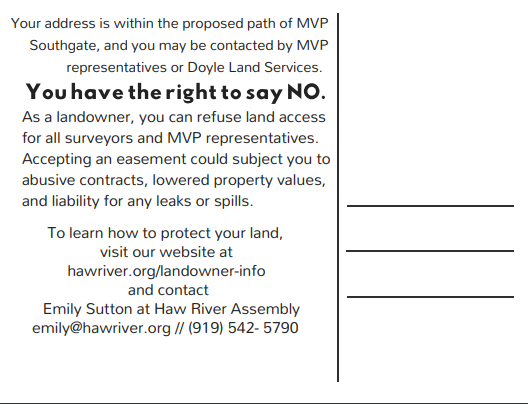

Sutton got a SHAPEfile in July from the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. The file, which had the proposed route’s geospatial coordinates, enabled her find the address of every landowner along the proposed route. In partnership with the Sierra Club and Appalachian Voices, which have also taken lead roles in opposing the pipeline, the Haw River Assembly sent postcards to every home along the route. Their message: You have rights. This isn’t a done deal. Here’s more information.

Lesson six: Learn what your priorities should be from the community.

Landowners told Sutton that the surveyors working for MVP were confrontational and hostile. She added a section to the website explaining how to file a complaint about the surveyors with the Department of Justice. The group also listened to members to develop how-to guides: How to write a letter to the editor. How to talk to people who are pro-pipeline. How to go to a public meeting and talk to your town council.

Lesson Seven: Your supporters’ stories are a powerful tool.

In November, Haw River Assembly held a regional community strategy summit with Sierra Club and Appalachian Voices, training 50 people on how to craft personal narratives to share with neighbors, proponents of the pipeline, elected officials, regulatory agencies, and reporters. With a new opportunity open to comment to Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the leaders emphasized the importance of individual comments, and trained each participant on how to navigate the commission’s database to submit comments, or file as an intervener, a status that gives you the right to sue FERC over the project. That deadline was Dec. 10, 2018. More than 228 grassroots activists submitted comments; 40 individuals and groups filed as interveners.

Lesson eight: Be a presence. Get on the agenda.

Sutton and the activist landowners spoke during at least nine town and county council meetings and worked to be added to the meetings’ agendas, which meant three landowners could speak for three minutes each about how the pipeline would affect them.

The group lobbied the conservative Alamance County commission to add the pipeline to its agenda. Haw made a presentation at a commission meeting, as did MVP. After the Bollingers spoke out, a commissioner arranged a visit to their farm. In September, the commission approved a resolution opposing the pipeline.

“Politically, you’re on opposite ends of the spectrum, the people involved, from the far right and the far left, but you can achieve something, working together, without compromising your principles and beliefs,” Kelly Bollinger said.

The district’s congressman, Mark Walker, and the state’s Department of Environmental Quality have also sided with the pipeline’s opponents. The Department of Environmental Quality sent a letter to Federal Energy Regulatory Commission saying, “we remain unconvinced that the Southgate project is necessary. We question whether the project satisfies the criteria for the commission to deem it in the public interest.”

Lesson Nine: Activism changes outcomes

“Where the original proposed route is and where it is now, it basically goes around our neighborhood,” Daniel Bollinger said. “We raised so much of a fuss, they said, ‘We’re going to leave these people alone.’ If we had more people pushing back where we were pushing, it would have changed where we are right now.”

“We have hopes and dreams for our farm,” Daniel Bollinger said. “To think someone could come in and take us. … That’s why we haven’t said, ‘It’s not affecting us now, we’re stopping.’

It’s not affecting us now, but who’s to say next year another one doesn’t come?”