By Venkatesh Dutta, Gomti River Waterkeeper

Many people living close to the riverbanks in the Ganga Basin, including the Gomti River, believe that there has been a drastic improvement in the water quality of the region’s rivers since the lockdown caused by the novel coronavirus outbreak, which was imposed in India on March 24, 2020 (See NDTV, India Today, The Hindu, BBC). The water in the river Ganga and many of its tributaries has looked much cleaner, with sightings of even endangered Gangetic dolphins at several stretches (See India Today, Times of India, Hindustan Times). Due to the lockdown, industries were closed for almost six weeks, which resulted in significant improvements in the water-quality parameters. Partially treated or untreated domestic wastewater continues to be the major source of pollution, by volume. Industrial wastewater contributes to just 10 percent of the total pollution load; however, its relative toxicity is more than domestic wastewater due to higher inorganic and toxic impurities.

Overall, the self-cleaning capacity of our rivers has also increased as a result of increased flow. With no toxic wastes and effluents, our rivers have seemed to get a new lease on life. But the hard truth is that this is a temporary reprieve. Things will start deteriorating once we return to normal.

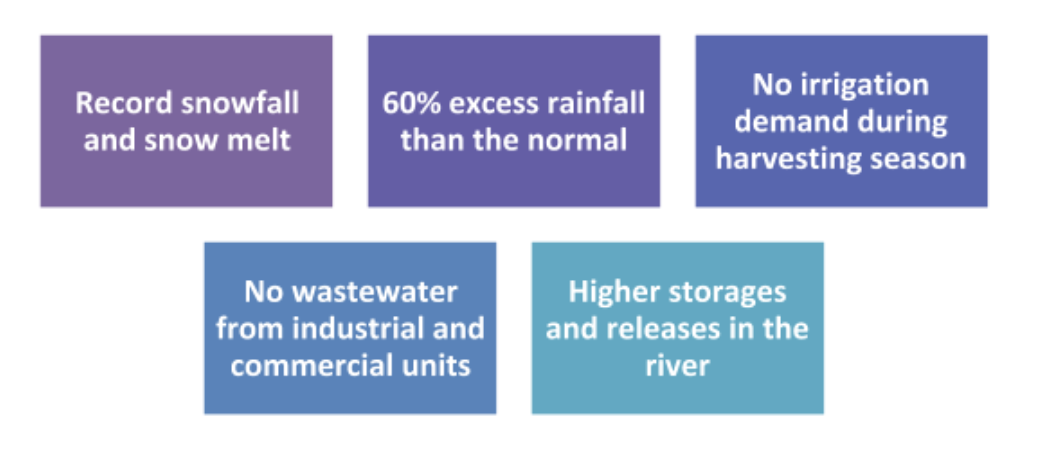

In addition to the lockdown, many other factors contributed to the increased flow in the river that aided in the dilution of pollutants. First of all, the entire Ganga Basin (nearly 26.2 percent of the total geographical area of India) experienced 60 percent above normal rainfall during the first seven weeks of the lockdown period. There were many events of western disturbances that led to heavy rainfall during March and April, and into the second week of May. This meant that more water was flowing in the river than the typical lean season flow characteristic of April and May. Even snowfall during the last two winters over Gangotri Glacier (that feeds the source of the Ganga River) was much more than the average — it almost broke the record of the past two decades. The state of Uttarakhand, which forms the upper Ganga basin, received six times more snowfall in 2019 (17.9 inches) as compared to 2018 (3 inches); and 2020 recorded almost 17 inches at the start of the year itself. With melting of the snow, more water was coming in the river. The storage data shows that the basin recorded 85 percent higher storage until the first week of May than the past ten years’ average.

In India, harvesting season falls during April to June, when winter cereals are harvested. This also contributed to increased flow in the Ganga as demand for irrigation water from canals (largely extracted from the Ganga and its tributaries) was nil.

The improvements that we are witnessing may be short-lived as we return to business as usual. But there are signs of optimism. Watching our rivers revive so dramatically, it is hoped, will spark an awareness that we must seriously look into all possibilities to restore their flow and make our rivers drinkable, fishable and swimmable again.

For example, the current irrigation method is largely flood irrigation, which results in huge losses of precious freshwater. If we move to precision irrigation technologies such as drip, sprinklers and so on, we can reduce the water footprints of crops that depend upon river water. Also, smaller tributaries should be restored so that freshwater from them can feed the main stem of the river.

There are many challenges for river rejuvenation — but with determination and commitment we can gradually see our rivers flowing with life again, in our own lifetime!

Venkatesh Dutta is the Gomti River Waterkeeper based in Lucknow, India.

Feature image: Gomti River at Lucknow Utter Pradesh in India by Nairitya/Shutterstock