Most people know about the attack on Pearl Harbor, but few know the vibrant natural history of the place Native Hawaiians call Wai Momi (Pearl Waters). Oysters were once abundant in these waters, playing a meaningful part of many ancient Hawaiian chants, songs, and legends.

Sadly, their numbers have declined steadily over the last century.

In response, O‘ahu Waterkeeper, the U.S. Navy, and the Pacific Aquaculture and Coastal Resources Center at the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo are working together to use native species of shellfish to improve water clarity and quality in Pearl Harbor.

Pearl Harbor sits at the bottom of a drainage system that stretches from the town of Aiea to the town of Ewa, which are about 13 miles apart. Stormwater, wastewater, and other contaminants flow into the harbor. Oysters are filter feeders; as they eat, they remove sediment, bacteria, heavy metals, PCBs, oil, microplastics, carbon, phosphorus, and nitrogen from the water.

The oyster initiative builds on a successful feasibility study conducted by the Division of Aquatic Resources in the state’s Department of Land and Natural Resource, which used Pacific oysters, a non-native species, to improve clarity and quality of waters within Pearl Harbor.

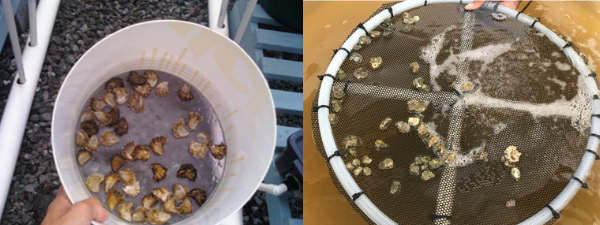

The new project will focus on native shellfish species because of their deep cultural significance. It will use two shellfish species native to Pearl Harbor: Dendostrea sandvicensis (Hawaiian Oyster) and Pinctada margaritifera (Black-Lipped Pearl Oyster).

When oyster larvae are permanently affixed to a surface, it’s called spat. The first spat, of approximately 500 native oysters, was planted in Pearl Harbor in June, with many thousands of oysters scheduled for deployment in the coming months. Navy command, joined by Waterkeeper Alliance President Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., and renowned master navigator Nainoa Thompson, President of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, joined representatives from University of Hawai‘i to celebrate.

The celebration illustrated how projects can grow organically, building individual efforts into a spat of new growth.

The navigator Nainoa Thompson and the Hokule‘a, the revered Hawaiian voyaging canoe, sailed into New York’s Hudson Bay in 2016 and visited the Billion Oyster Project. Nainoa expressed his deep desire then to launch a similar school in Hawai‘i to restore native oysters.

The Navy, also in 2016, was considering bioremediation in Hawai‘i and the Pacific. This concept was initiated by a proposal for Pearl Harbor oyster restoration from Marian Phillipson, who was serving at the time as the Executive Director of Discover Wai Momi, whose goal was to develop a waterfront science education center.

Rhiannon “Rae” Tereari‘i Chandler-‘Iao began work establishing O‘ahu Waterkeeper, the first Waterkeeper program in Hawai‘i, at around the same time.

The larval idea started taking hold: Rae visited New York’s Harbor School and learned about the Billion Oyster Project. Rae invited Marian to be a board member of O‘ahu Waterkeeper; together, they reached out to Dr. Maria Haws, Director of the Pacific Aquaculture and Coastal Resources Center at the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo, a bivalve expert in the State of Hawai‘i.

The rest is oyster history.

The University now provides technical expertise and produces native oysters and shellfish for the project.

In addition to Pearl Harbor, spats of native oysters are growing at the Marine Corps Base in Kane‘ohe Bay and in the Ala Wai Boat Harbor on O‘ahu, work done in partnership with the Hawai‘i Yacht Club.

“We want children to be able to visit the oysters and learn about environmental issues such as stormwater, wastewater, water quality, and fishing safety,” Chandler-‘Iao explained.

The O‘ahu Waterkeeper is currently working with the Polynesian Voyaging Society on an environmental education curriculum that will use native oysters to educate students and the community on fundamental water issues.

About ten University of Hawai‘i at Hilo students, as well as recent graduates, are working on the native oyster project, Dr. Haws said.

“There’s a great sense of gratification from knowing that our goal here is to put the native species back in the water for restoration purposes,” said Daniel Wilkie, a former UH-Hilo student and Pacific Aquaculture and Coastal Resources Center’s research manager. “It feels good to know that I’m contributing to the community by reinvigorating the native species. We know with invasive species and over-collection, a lot of the Hawaiian reefs are dramatically different from the way they used to be. Any way we can try and restore the natural habitat is incredibly rewarding.”

Feature image of the native oysters, Dendostrea sanvicensis, by Dr. Maria Haws.