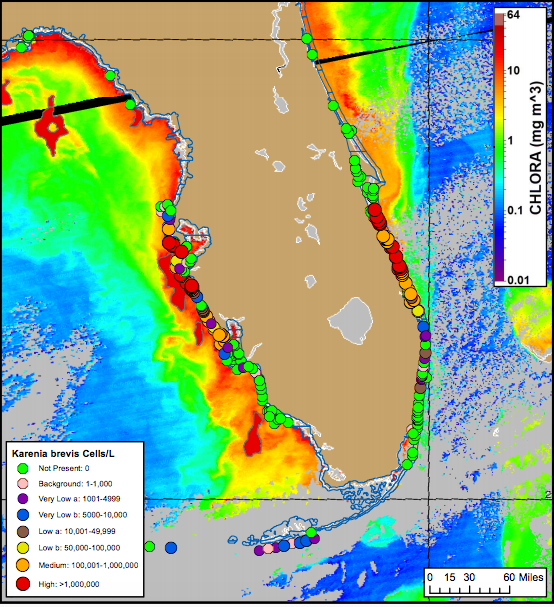

A 70-mile-long stretch of the Caloosahatchee turned into a river of blue-green slime this summer, as an algal bloom blanketing the river sludged its way to Florida’s Gulf coast. At the same time, the Gulf coast was reeling from red tide, a different algal bloom — one that many scientists believe is caused by nutrient pollution and cyanobacteria (blue-green algae).

It was a glaring example of the interconnectedness of biosystems — and the Band-Aid policy decisions that imperil them.

The blue-green slime algae on the Caloosahatchee was fed by nutrient pollution in Lake Okeechobee. Nutrient pollution in Lake Okeechobee comes from Big Sugar and industrial animal agriculture, urban stormwater, and leaky septic systems. That intensive nutrient pollution means Lake Okeechobee suffers from its own debilitating algal bloom, which was especially bad this year.

So a lake full of algae turns a river into slime, which then dumps into a Gulf awash in dead fish from red tide.

Here’s where the Band-Aid policy comes in: The Army Corps of Engineers is spreading Lake Okeechobee’s pain.

To avoid stress on the aging Herbert Hoover Dike that holds Lake Okeechobee in place, the Army Corps releases water from the lake into the Caloosahatchee River on the west and the St. Lucie River estuaries on the east.

Those releases of algal, nutrient-polluted water from Lake Okeechobee are what turned the Caloosahatchee into a river of guacamole over the summer. In turn, the releases may also have contributed to a red tide in the ocean so deadly that one Florida county bought heavy machinery to remove dead fish from its beaches.

As the slime coating the Caloosahatchee recedes, the question for decision makers in Florida, as well as those at the Army Corps, is when they’ll start looking at waterways as natural systems that affect each other. After all, this is a situation where more than a Band-Aid is required.