By Sharon Khan and Gabrielle Segal

Waterkeeper Alliance has launched Project Osiris — an ambitious and achievable plan for drinkable, fishable, and swimmable water around the world. It is aptly named after the Egyptian god of resurrection and regeneration who periodically flooded the river to provide fertile cropland along the Nile valley.

Today, the Nile River Basin is vital to the survival of over 300 million people. Endowed with about one-third of the world’s fresh surface water, the Nile River breathes life. When viewed from above, the abundance of life is obvious as flourishing greenery and civilization encompass the river, in an otherwise arid, almost unlivable desert.

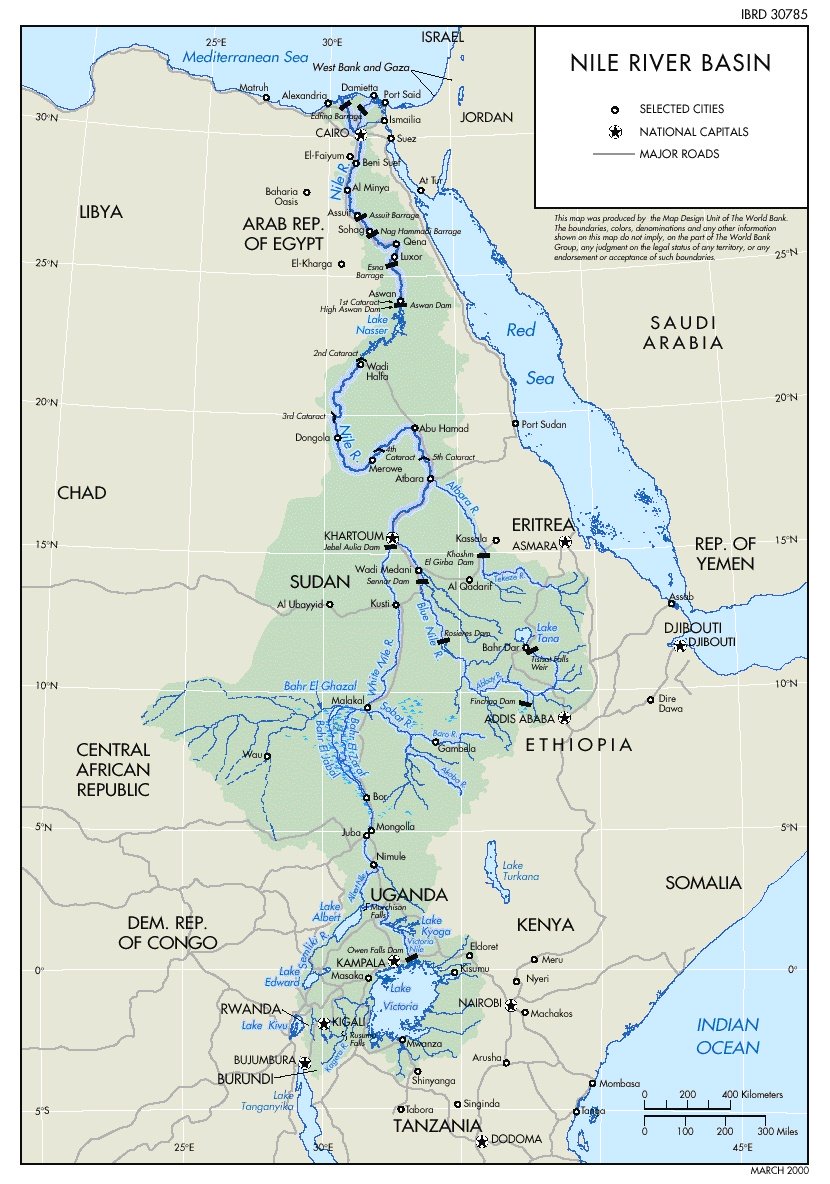

Flowing south to north, the Nile River Basin spans 11 countries: Tanzania, Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, South Sudan, Sudan, Ethiopia, Egypt, and Eritrea. The Nile River has two branches which meet in Sudan before flowing into Egypt. The White Nile rises from the African Great Lakes Region, and the Blue Nile originates from Lake Tana in Ethiopia.

Three Waterkeeper organizations are now located in the Nile River Basin, at the headwaters of the White Nile in the African Great Lakes region: Kenya Lake Victoria Waterkeeper founded in 2015, Lake Kyoga Waterkeeper in Uganda (2017), and Tanzania Lake Tanganyika Waterkeeper (2018). The White Nile that flows from Lake Victoria to Lake Kyoga is most noticeable on a map as the start of the river.

All of the Nile Basin countries have their own set of rules and regulations related to the river; their lack of coordination can be destructive. For example, a recent study showed that over 100 intended agricultural deals made among various investors and nations between 2008 and 2013 would require more water than actually flows in the Nile.

The Nile River Basin is a major scene of water crisis, with conflicts constantly erupting around how water is used in the region. Most recently, warnings have been sounded of a potential water war as the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam nears final construction on the Blue Nile in Ethiopia. Upon completion, it will be Africa’s largest hydroelectric power station and one of the largest dams in the world. The dam’s reservoir will be bigger than Greater London. As Ethiopia strives to transform itself into a middle-income country, with electricity running throughout, Egypt, its neighbor to the north, is concerned that Ethiopia could control the flow of the Nile — as it is the Blue Nile that provides Egypt with more than 80% of its water. With Ethiopia’s goal to generate power as quickly as possible, Egypt is trying to negotiate with them to fill the dam’s reservoir at a slower rate, over six to twelve years instead of three. Meanwhile, Sudan is supportive of the dam for the energy and irrigation benefits it expects to see.

In 1999, well before this current crisis, the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) was established “to provide a forum for consultation and coordination among the Basin States for the sustainable management and development of the shared Nile Basin water and related resources for win-win benefits.” In 2017, the NBI presented its 10-year Strategy. The second of six goals in the strategy is to “enhance hydropower development in the basin and increase interconnectivity of electric grids and power trade.”

Grassroots attention needs to be given to this goal. Ambitious hydroelectric power plans may not even benefit the 60% of local communities that are not connected to the grid. Additionally, another report from the NBI recognizes that “total power demand will eventually exceed hydropower potential, and alternative power sources will need to be developed.” Now is the time to pay greater attention to safe renewable energy, like solar and wind – which do not appear in the 10-year strategy. Governments do not need to fight over the sun as a resource.

“The strategy needs to be re-conceptualized to benefit from a full energy security portfolio as opposed to a singular focus on hydropower,” says Leonard Akwany, Jr., Kenya Lake Victoria Waterkeeper.

Climate change has created severe drought in much of East Africa, punishing some of the world’s poorest people with extreme famine and food insecurity. Plus, with the population of Africa expected to double by the year 2050, more strain will be placed on a land where many countries are expected to face water shortages in the near future. Similar to Cape Town’s ‘Day Zero,’ the United Nations predicts that Cairo, the capital city of Egypt, could run out of water by 2025.

With such a grim outlook, the efforts of Nile Basin countries to come together to create sound water management plans are critical. As natural and man-made threats to the basin increase, the need for cooperation and agreements among all nations involved is dire. Grassroots community stakeholder input is crucial to these efforts, to ensure that people have access to drinkable, fishable, swimmable water.

Waterkeepers in the Nile Basin are working on many issues in common: mainly, destruction of wetlands for development, agricultural pollution, lack of waste treatment, and destructive fishing practices. Together, these Waterkeepers can become a strong unified grassroots community voice for the region. By joining together under the Waterkeeper Alliance umbrella, they can strategize on the best management plans for watershed protection, and show how communities can naturally work together across nations.

Kenya Lake Victoria Waterkeeper and its sponsoring organization Ecofinder Kenya, led by Leonard Akwany Jr, protects the northeastern part of Lake Victoria, the largest of the African Great Lakes that borders three countries: Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. It is the second largest lake in the world by surface area, the 9th largest by volume, and serves a population of about 30 million people. Leonard has also been an active participant in NBI’s work, advocating regionally for nuanced attention to wetlands, freshwater ecosystems, and biodiversity.

“Through my consultancy work with the NBI on transboundary wetlands, I have been pushing for the environmental sustainability agenda. As a network of Waterkeepers, we need to advocate for reforms in the NBI work – that can be contradictory in itself. For economic reasons and to remain attractive to state parties, they over-rely on hydropower and multi-purpose dams as investments. There is great fodder here to advocate for improvement in environmental sustainability for the Nile River Basin,” says Leo Akwany Jr., Kenya Lake Victoria Waterkeeper

Now, Goal 4 of the Nile Basin Strategy is to “protect, restore and promote sustainable use of water-related ecosystems across the basin.” Yet it notes that “the challenge therefore is how basin countries collectively ensure that the ecosystems of the Nile Basin are sustainably managed in order to guarantee continued provision of ecosystem services to basin inhabitants.” As a collective force, Waterkeepers are prepared to rise to this challenge.

Every February 22nd, NBI promotes Nile Day, and every three years they host a forum. The 2018 Nile Day was held in Ethiopia, while Kenya Lake Victoria Waterkeeper was reporting on its climate change adaptation work at an East Africa stakeholders meeting in Tanzania. The time is now for Waterkeepers to prepare for the next forum in Ethiopia in 2019. Under Project Osiris, we plan to strengthen and grow a network of Waterkeeper organizations and affiliates in the Nile River Basin, to raise public awareness, gather scientific evidence of the pressing threats to their waterways and ecosystems, advocate for protection — and celebrate the Nile. Join us.