By Andrew Kelly (Yarra Riverkeeper), John Forrester (Werribee Riverkeeper), April Seymore and Neil Blake (Port Phillip Baykeeper)

From 1996 to 2010, Australia suffered its Millennium Drought. The driest spell in centuries inspired the country to undertake a series of water management changes to balance water between production and ecological needs on a drought-vulnerable continent. So: nearly a decade into these investments, why did Australia enter 2019 with the first bone-dry riverbeds in cultural memory, and hundreds of thousands of dead fish?

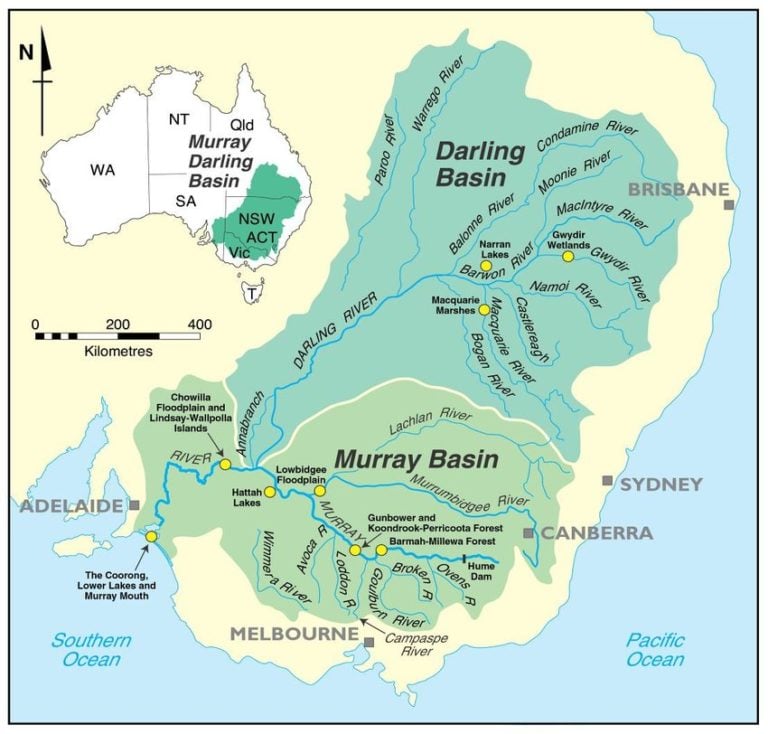

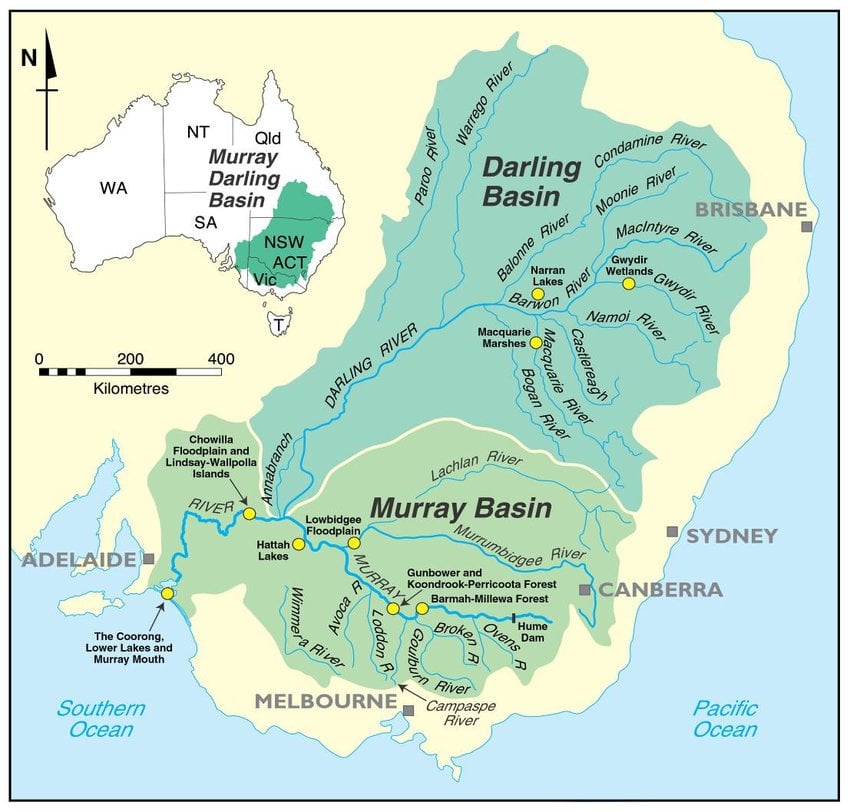

The Murray and Darling Rivers are Australia’s longest, most iconic inland rivers and the largest river basin, stretching over five Australian states and territories and 40 Nations of Aboriginal Traditional Owners. The river system has supported 40,000 years of continuous culture for the river peoples, and currently grows 40% of Australia’s food. Extraction of large volumes of water for agricultural cropping diminishes the capacity of the basin to provide for hundreds of native land and water animals including 51 endangered species.

Flowing through rugged mountains and semi-arid plains, the riverine ecosystems are unique with a large number of endemic species, including the Murray Cod, Murray River Turtle and specialized crustaceans like the Spiny Freshwater Crayfish. The survival of many threatened bird species is reliant on quality vegetation, waterways, and wetlands including the 17 RAMSAR-listed wetlands of the Murray-Darling.

The catchment lies over most of the world’s largest and deepest artesian basin, which recharges through sandstone and supplies many towns, industry, farms, people and the environment in the Murray-Darling Basin with quality freshwater.

Modern water access and diversion have been lopsided. Water quality and quantity have been compromised by mining and fracking. Extractions were licensed with little analysis of their impacts on communities downstream. Environmental flows have been considered only since the 1990s, and Indigenous groups systematically excluded from water equity discussions. Cultural water rights were only recognized in 2004 and two Aboriginal Nations Alliances still struggle to have their claims for water rights heard amid the more influential concerns of the irrigation, environmental and scientific sectors.

To rebalance water diversion, Australia created a “water market” including the environment as a shareholder. Water shares can be bought either as entitlements or temporarily as a water allocation. In 2011, interstate management was brought together under the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, with ambitious targets to return water for environmental use through buyback schemes and multi-billion-dollar irrigation efficiency investments.

The water market enabled Australia to come through the Millennium Drought without a reduction in agricultural production, yet is an immature market that is dealing with a property right unlike other property rights, and has had its share of problems. The market has been beset by devious decision-makers in cooperation with irrigators, often to farm thirsty cotton crops mismatched for Australia. Kevin Knight, Barkindji elder from Bourke says, “There are too many water licenses and too much pumping.”

The “world-leading” Murray-Darling Basin Plan has flaws such as excluding drought datasets in calculations, despite climate change intensifying Aussie drought cycles. The Plan has been beset by political conflicts of interest, including gaming of the rules by the upstream states of New South Wales and Queensland at the expense of the downstream states, in particular, South Australia. There has been a lack of independent auditing of the effectiveness and socioeconomic impacts of interventions thus far, and the perverse assignment of the Murray-Darling Basin Authority to officially regulate itself.

And now, the inconveniently visible fact of over 100,000 dead fish in the first month 2019. (With culturally totemic land and river species starved of water, Gamilaraay elder Virginia Robinson says, “This to me is the ultimate destruction of our culture.”) The death of fish up to 40 years old is attributed to oxygen starvation, due to a sudden drop in temperature and the subsequent decay of blue-green algae which had exploded in the warm conditions in the Darling River.

Nine out of ten Australians reside in a handful of urban capital cities, with much of our water dependence hidden behind our garments, our goods, and our food. Rural and remote residents, however, often are farmers and Indigenous communities with fierce immediacy to their struggles with and connection to water and drought. Periodically, vivid exposés about water theft or fish deaths remind urban citizens of the pain and (presumed) failures of the mammoth Murray-Darling Basin Plan and the challenges faced by an innovative but immature water market. Calls for reform and accountability to an independent expert body are rising, and will be a hot issue in the upcoming Federal Election – we only hope it won’t be too late.

*Feature image: Lake Hume at 4% volume. Photo credit: Tim J Keegan (Creative Commons)