By Anna Alsobrook, Watershed Outreach Coordinator at MountainTrue

As MountainTrue’s Watershed Outreach Coordinator, I facilitate volunteer water quality monitoring and restoration programs in the French Broad River watershed. When it comes to our water quality monitoring, performed under our French Broad Riverkeeper program, we field a lot of questions from the public on what E. coli is and when they should be concerned. Here is some helpful facts about E. coli to get you up to speed on Escherichia coli—E. coli.

How does E. coli get into water? We get increased levels E. coli in our waterways in three ways: It enters streams through agricultural runoff, it comes in from leaking sewer or septic infrastructure, and lastly, there is legacy bacteria that gets churned up during rain events. E. coli adheres to sediment particles, and during dry times, those particles fall to the bed of the river. When a storm rolls through, the sediment gets churned up into the water column, and more of it ends up in our water sample. How much of the E. coli is new influx versus old legacy bacteria is something we are still researching.

The reason we test for E. coli is because it is the best indicator for the presence of disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and protozoans. This does not mean a river without E. coli is always safe, nor does it mean that a river with some E. coli is a cesspool of pathogens. But there is a proven positive correlation between the presence of elevated levels of E. coli and illness or infections.

French Broad Riverkeeper samples once a week, each Wednesday morning. It takes approximately 18-24 hours of incubation before we get the results, which we usually post by Thursday afternoon on theswimguide.org—which delivers free water quality information for over 7,000 beaches, lakes, rivers, and swimming holes in eight countries. We use some of the best available technology in E. coli monitoring. We’ve cut down wait time from nearly half a week to less than a day, but it still takes several hours before we can post our results. So, it’s important to remember that our Swim Guide results are a snapshot in time, and, as you all know, the river is a dynamic entity, and can change at any moment due to weather and/or human influence.

That means that if it rains Tuesday night or Wednesday morning our testing results might be really high, but if we have five days in a row without rain, E. coli levels could be dramatically lower by Sunday. The opposite is true as well. If we test in the middle of a dry spell but then it rains on Wednesday evening, E. coli levels could spike but our testing will not have picked it up.

That’s why it’s so important to pair the information we provide to the public on Swim Guide with your own best judgment. E. coli is directly linked to rainfall and sediment. If it rains and the river is running muddy, chances are that E. coli levels are higher. If there’s been little to no rain and the river is running clear, chances are that E. coli levels have dropped. We had a dirty week last week, we could very well see a much cleaner week this Thursday.

We’re always striving to make our monitoring program better, faster, and more accurate. Right now, we’re working on a statistical model that could predict E. coli levels based on other, more immediate water quality parameters. Doing so would give us a sense of E. coli levels in real-time.

We do this work to inform folks wanting to recreate in the river how safe it is for swimming. The standard we use for “safe waters” is the EPA’s BAV standard of 235 cfu/100ml. When levels reach that high, the EPA estimates that for every 1000 “primary contact recreators,” aka people, 36 of them will get sick or an infection. Primary contact recreation typically includes activities where immersion and ingestion are likely and there is a high degree of bodily contact with the water, such as swimming, bathing, surfing, water skiing, tubing, skin diving, water play by children, or similar water-contact activities.

Beyond just monitoring, we are also working hard to track down and eliminate leaky sewer and septic systems. We have partnered with Buncombe County Metropolitan Sewer District on this work and have fixed several issues within the last couple of years. We are also advocating for state funds to re-institute North Carolina’s Wastewater Discharge Elimination Program (WaDE). Its purpose was to find and eliminate discharges from straight pipes and leaky or failing septic systems. During its tenure, it was highly successful in surveying watersheds, finding these discharges and facilitating (and at times helping to finance) their repairs. The program lost its funding, and the progress it made has since stopped. One of the things MountainTrue Riverkeepers (Broad, French Broad, Green, and Watauga Riverkeepers) are fighting for is to bring this program back.

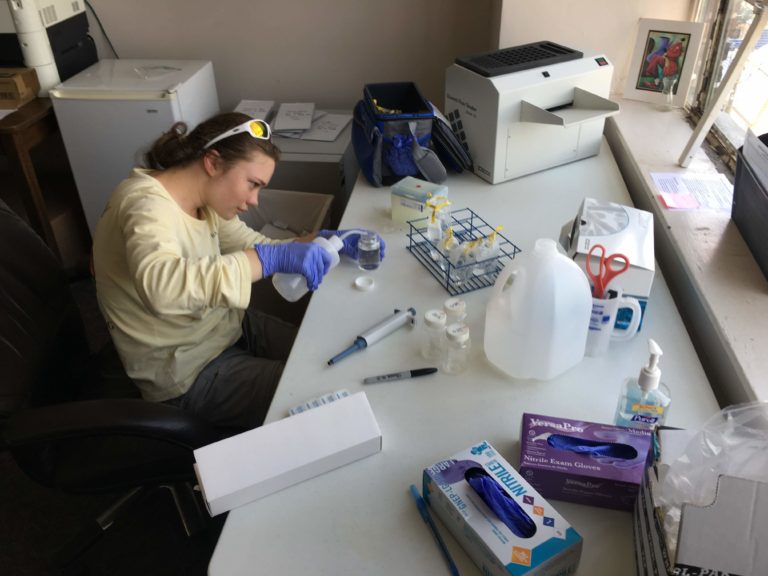

Feature image: Olivia Votava of our water quality team tests water quality samples for the presence of E. coli bacteria at MountainTrue’s Asheville lab.