There At The Founding

By: Waterkeeper Alliance

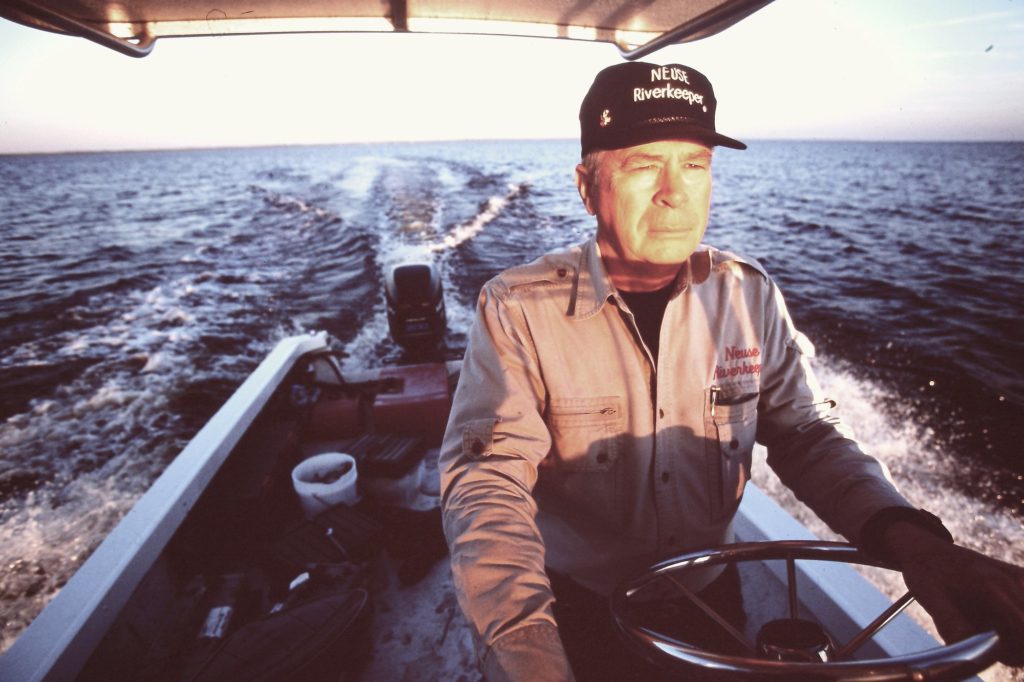

In this roundtable discussion, which took place about 18 months ago at a Waterkeeper Alliance annual conference, five of the earliest Waterkeepers – Neuse Riverkeeper Rick Dove, New York/New Jersey Baykeeper Andy Willner, Chattahoochee Riverkeeper Sally Bethea, Casco Baykeeper Joe Payne and the late Long Island Soundkeeper Terry Backer, the movement’s longest serving Waterkeeper, who passed away on December 14, 2015 – reflected on their connections to water, their first years fighting for their waterways, and their wonder at how their belief in each other and in the power of following their deepest convictions spawned a world-changing grassroots movement that is now on the frontlines of the global environmental crisis on six continents.

RICK DOVE:

My earliest memories of water were when I was six or seven years old…

…growing up on the Chesapeake Bay. The only thing I ever wanted to do, even as I grew older, was to be around water, be a fisherman, a tugboat captain, anything, just to be near water. My folks talked me out of that and told me, you just can’t support a family on that alone. So I went to college, but I never turned loose that dream of somehow, someday working on the water.

I joined the Marine Corps because the draft was chasing me. As it turned out, I liked it a lot, so I stayed for 25 years. But for all that time, there was something running through my veins that told me that someday, somehow I would get back to working on the water. And when I retired from the Marine Corps, I remember walking out the gate in my spiffy uniform, and going home and getting into my oldest, dirtiest clothes, and grabbing my son. I told him, C’mon, we’re going fishing. And we went down to the Neuse River, got in our boats, and started fishing.

For about three years, I was having probably the happiest time of my life. But then, all of a sudden, the fish began to die, and there were huge sores all over their bodies, and I got the sores on me, and my son got sick, and we had to give it up. It was right about then I recognized that maybe there was another calling for me – to find a way to get involved with somebody, some organization, so I could fix the problem that was denying me the one thing I really wanted, even as a kid.

ANDY WILLNER:

When I was a very young child, my parents took us for a vacation up in the Pocono Mountains. It was a big lake…

…and there was this little area they called the crib where little kids were supposed to swim. They let me go in there, and the minute I realized that you could swim underwater is when I realized how much I wanted to be in the water. It was, I think, that lesson that carried me through my life. Of course it scared the crap out of my parents, because I disappeared for more minutes than they thought anybody could stay underwater.

It was that feeling of being immersed, being really at home in that medium, that made me look for ways that I could be on, near, or in the water for the rest of my life. And I think that the frustration that brought me to Waterkeeper was when I had a boatyard in Staten Island, and my daughter, who was probably six or seven, was hot. It was summertime, and she couldn’t go in the water of New York Harbor because I knew that it was so polluted it was off-limits for swimming.

I was just furious. Here we were, surrounded by this beautiful body of water – there was actually a beach down the street, but she couldn’t go swimming. So I wound up filling an old plastic dinghy full of water so she could splash around. And I think that frustration and deciding that I needed to do something about it led me to become the Baykeeper.

SALLY BETHEA:

I grew up in the 1950s and 1960s, living next to a little stream on the outskirts of Atlanta. It had crayfish, snakes and all kinds of little fish.

The water was really clear. I loved playing in the creek. I was a little bit of a tomboy. My parents also took us to a wonderful barrier island off the west coast of Florida in the ‘60s, and there we would play, walk the shores, look for seashells, and I just developed this love for the natural world.

Fast-forward to the ‘70s. It was a time when there were rivers that were so polluted with industrial waste, like the Cuyahoga in Cleveland, that they actually caught fire. People in Georgia were just waking up to the fact that Atlanta was going to grow and develop at a tremendous rate. Finally, a highway was proposed through the north Georgia mountains, cutting across major river basins including the Chattahoochee, and I thought there’s got to be something I can do. That’s when I got involved in environmental advocacy, first with several environmental groups and federal agencies, and then I had the lucky break of a lifetime and heard about Waterkeeper. I became the Chattahoochee Riverkeeper 20 years ago. It’s been an incredible blessing; it’s been a place where I could channel both my outrage and my hope.

JOE PAYNE:

My first memories of water are growing up on Peaks Island in Casco Bay [Maine]. I’d always be at the shore and turning over rocks and gathering periwinkles…

…to eat, to use for bait, swimming on one side of the island, then doing a circuitous route over to the other side. Island life gives kids confidence. Your parents are freer to let you go because that village is going to let them know right away if you did something wrong or if you got hurt. It was a great, great experience.

My grandfather was a waterman, a fisherman on Casco Bay, and my first water experience was the summer before I was born. My mother, pregnant with me, traveled back and forth all that summer on my grandfather’s boat from Portland to Peaks Island. So I go back to in utero for my first water experience.

He had a big family – ten, eleven kids, but none of them felt the pull of the water the way I did. I don’t know how that happened, but Casco Bay, the life on the water, it hit me hard. I liked the sciences, and when I took biology and found out that our blood and seawater are 98 percent the same, that was kind of a justification for why I had to be in, near, under saltwater.

Andy was talking about being underwater. When I was in high school, I took a tenweek-long scuba course, and for five weeks all we did was learn stuff and swim laps every time someone got cold. I learned to not like people who get cold easy. But on the sixth week we got to put on a tank and a regulator and go underwater, and I will never forget that feeling. It was only 10 feet in the deep end of the pool, but sitting on the bottom looking up and not having to come up, that was the start of it. I became a diver, then a research diver, and I went to school to become a marine biologist.

We have 5,400 miles of coastline in Maine, but I couldn’t find a job as a marine biologist, so I had to go away. I worked on the Great Lakes, on Lake Ontario quite a lot. Then I heard about a job in New Hampshire in marine biology, and I took that. Then this organization called Friends of Casco Bay advertised for a Baykeeper, and I looked and looked at it. My wife Kim and I both had great jobs. We had a passive solar house on 12 acres. Everything was fantastic. I kept the paper beside the bed for two weeks. I didn’t say anything to Kim. This job sounded great, but I was thinking, where will Kim find a job in Casco Bay? I showed her the ad two days before the deadline. She said, “You’ve got to try.” I said, “Yeah, that’s it. I’ve at least got to try, just so I won’t always wonder.” They offered me the job, and, boy, I haven’t looked back now almost 24 years.

TERRY BACKER:

For me water was just always there. My dad was a lobsterman and oysterman on Long Island Sound, like his father and his father before him, going back generations.

So I can’t say there was ever an awakening to water. I can remember being a little kid on my father’s lobster boat looking up at him with his hands on a spoked wheel and that boat cutting through the water. I said, “Well, this is me. I’m going to be a fisherman, too.”

I used to lean over the side of the boat and wait for the lobster trap to come flying up out of the bottom, and I worked on the boat with my father for many years. Then I got the urge to try some other kind of fishing, and I headed out to the West Coast and ended up in Alaska working on salmon seiners and down the coast of the Pacific Northwest and Puget Sound working on fishing boats. And eventually I’d got the urge to come home and work with my father again.

When I got back, we were headed down the river one day, and I looked over the side of the boat and there were rafts of brown, foamy stuff floating on the water, and I said, “Hey, Dad, what is all that crap?” And he said, “That’s what it is.” Towns were just dumping their raw sewage right into Long Island Sound. And I got to thinking and worrying about it.

When we needed lobster bait, we’d go up the Hudson River to buy buck shad up past the Tappan Zee Bridge. The Hudson had a pretty bad reputation for being so polluted by then. Looking out at the river, I turned to a Hudson River fisherman, Bobby Gabrielson, and I said, “I always had the impression an atheist could walk across the Hudson River.” And he said, “Well, we got a Riverkeeper here now and things are starting to change for the better. You ought to go up and see him in Cold Spring – John Cronin.” So we got talking to John Cronin and Bobby Kennedy, and they said, “You guys have got to take those towns and their politicians to task, challenge them, and you can do it in court through the Clean Water Act,” which had been passed in 1972 and gave citizens greater power than ever before to bring their own lawsuits to stop illegal pollution. “You can prosecute them and you can use the law to force them to stop polluting.” So we formed the Connecticut Fisherman’s Association with another lobsterman named Chris Staplefelt, and a few other fishermen came on board, and we brought our first citizen suit against five or six different towns for violations of the Clean Water Act – some of them up to 50,000 violations.

We went in the court with their own discharge-monitoring reports showing that they were violating the law, and they agreed to settle. Our first settlement was for certain benchmarks to improve the sewage-treatment plan in Norwalk, Connecticut. Our lawyers were pretty much volunteers from the Pace Environmental Litigation Clinic in White Plains, New York, which Bobby Kennedy, Jr., had created, and we won an $87,000 settlement.

Talking to Bobby and John, we decided to create a Long Island Soundkeeper, and I took on the job. I can remember my father leaning over to me saying, “You’re going to starve to death doing that, boy.” But here I am almost 30 years later, still the Long Island Soundkeeper, as long as God gives me breath and the strength to do it.

We started getting letters from some guy named Willner in New Jersey, and he said, “I want to be a keeper.” And I said to myself, “Well, if you want to be a keeper, go do it.” And one day down on the dock in our oyster house, along came Andy Willner, and he told us he was now the New York/New Jersey Baykeeper. And I said, “Well, now you’ve got it right. You’re not asking. You’re telling.” And then there was a Delaware Riverkeeper. And I had the great fortune to see more and more people wanting to be keepers, like Joe Payne in Casco Bay, Maine, and Rick Dove on the Neuse River in North Carolina, and, of course, Sally Bethea, on the Chattahoochee in Georgia.

At some point, John Cronin and I were talking, and we said, “We ought to create an organization to keep everybody on track, put a hub in the middle of this wheel.” I think that was my expression. So we started with the Alliance of River, Bay and Soundkeepers, and over time that morphed into Waterkeeper Alliance, which now supports over 270 organizations on six continents. Watching this movement grow has been the greatest pleasure of my life.

Water still means so much to me. It’s indelibly the deepest part of me. I vividly remember my father telling me it was time to learn to swim and taking me to the back of the boat and heaving me over the side into the river. And I kicked and splashed and panicked, but somehow my body started moving toward the boat. Of course I couldn’t climb up in the boat, so he fished me out. And I remember when my eldest son, who is 28 now, was born; I headed down the river to pull lobster traps with him perched on the motor box in a bassinet.

A newspaper commented in an editorial, “Remember Long Island Sound filled with sewage before Terry Backer and the Soundkeeper crew came along,” and it was then I realized that I had made a difference for the place where I lived, for the people I grew up with, for the culture I was raised in, and that other people followed and were doing it too. It’s a great feeling when I go to Waterkeeper conferences and see all these people from all over the world realizing and doing things that make a difference for themselves and the people around them and for the world.

If you were to go up to my dad, God rest his soul, and ask him, “Who are you?” he would tell you, “I’m a lobsterman.” Sometimes I feel that way. Who am I? I’m the Long Island Soundkeeper. I can’t think of anything more worthwhile that I could have done, and I am very grateful to my belief in God and to have been put here and to have found a way to be useful in my work.

AW: I think the one unifying thing about Waterkeepers is persistence. In order for me to become a keeper, I had to be persistent. At first, John Cronin threw my letters away; Terry threw my letters away. And they were the only two people to ask. But I still used them as models because I realized that they were really on to something, that what they were doing and how they were doing it was unique and powerful because it was rooted in private citizens taking responsibility for the shared resources that we the people own in common, that are our shared birthright. Right from the beginning, the Waterkeeper movement was, at its heart, a democracy movement.

That model was so vital, it was so vibrant that even in those early days we saw that it had to be codified in some way, organized so that we could make sure that the next person who came along and was persistent enough to become a Waterkeeper actually had a roadmap, or maybe I should say a navigational chart. We also wanted to make sure that they understood that this was a calling, that it wasn’t just a job. I think of the audacity of those early days. The first time we had an official meeting there were just seven Waterkeeper organizations. But there we were, seven of us in a room with the audacity to declare that we were an international organization. A circle of people were battling out what this movement was and could become, and some of the insights, some of the ideas were really earthshattering in the sense that we never had heard of a model like this: That independent grassroots organizations could work together toward a common goal without infringing on each other’s autonomy, and that an individual citizen could declare that he or she was the legitimate steward of a community’s waterway.

I can still remember the first time I was in a community meeting after I’d been the Baykeeper for a while and was called on to speak. I introduced myself as the Baykeeper and after I finished speaking no one disputed my legitimacy or what I had to say. I suddenly realized that it wasn’t just a title; that by being out there on the water, day in and day out, by protecting that waterway, I had proven that I had a right to speak for it.

We needed to invent something absolutely brand new. And we did it, and I think a lot of the reason we succeeded was because we were so damned persistent.

And that spirit has carried through, and I continue to see it in the men and women who decide to become Waterkeepers. Every one of them has a passion for the body of water they want to protect. I’d even say a spiritual bond. And I think that’s it’s that love of a particular place that’s the secret to the persistence that characterizes Waterkeepers, their readiness to confront and to overcome all the huge obstacles that Waterkeepers face all the time. Having served on the committee that reviewed new applicants for several years, I remember there were people who didn’t appear to have all the qualifications at first, but they came back three, four, even five times. They just wouldn’t take no for an answer. And they were so persistent that, finally, we said, well, dammit they have the most important qualification – they won’t take no for an answer. And we just gave in.

SB: My introduction to Waterkeeper was when Bobby Kennedy came south to Georgia and gave a speech for a candidate running for mayor in a small town. I was working for a mainstream environmental group, but I didn’t feel I was really getting anything done. I wanted something more aggressive, more focused and more place-based. And I remember hearing Bobby and writing notes on my hands, on napkins, to record all the things he was saying about all the things that the Hudson Riverkeeper was doing. I had no idea that two years later, in 1994, I would be in the right place with Ted Turner’s daughter, Laura Turner Seydel, and her husband, Rutherford Seydel, who were looking to replicate a Hudson Riverkeeper on the Chattahoochee River in Atlanta. And when I remembered the inspiration that I had gotten from Bobby and the excitement about this model, I stepped forward, hesitantly, in some ways, but also with a lot of excitement, because I wanted to be part of this movement.

There is no way I could have done it on my own without reading about what these guys had already accomplished and, later, talking to them and getting to know them, and picking their brains to figure out a way for a Southern woman to get the same sorts of results for a river that sustains nearly four million people. My great memory is going to Casco Bay in 1995 and walking into this room with men who mostly had big beards, and wondering what I’d gotten myself into, but also being completely engaged and entranced with their passion, their commitment, their knowledge. And I thought, boy, I don’t know how I’m going to do this, but I’m going to follow these great examples.

The family aspect of Waterkeeper has been really important. As we all know, families fight sometimes, but you’ve got each other’s back. Without Waterkeeper Alliance, without all these people that were fighting the same fights and dealing with the same frustrations, I could never have done this work.

RD: In 1991 we lost a billion fish on the Neuse River. I was still a commercial fisherman, and I was extremely depressed. After 25 years in the Marine Corps, I had never known failure. That’s the way it is in the Corps. And here I was with my son with failure everywhere we looked. I had sores on my hands from some unknown organism that was in the water. Fishermen were suffering from memory loss and some passed out in their boats. When they awoke, they couldn’t remember how to get back to their dock. Soon, many people along the lower Neuse began suffering these same symptoms. I wanted to do something but and I didn’t know where to start. Then I happened to read an article in the local newspaper about this environmental group, the Neuse River Foundation, looking for a Riverkeeper. What in the world was a Riverkeeper? I had no idea, but I liked the sound of it. I began to read about what John Cronin was accomplishing on the Hudson River and Terry Backer on the Long Island Sound and Andy Willner in his watershed, and I said, “Man, these guys are getting things done. They’re really making a difference.”

I had the same experience that Andy did at first. I was writing John Cronin letters saying, “I want to be a Riverkeeper,” and John didn’t answer. I kept writing, kept writing, and then one day I said, “I’m just going out and be a Riverkeeper for a while.” I wrote to a guy named Michael Herz on the West Coast who was working as the San Francisco Baykeeper, and he said, “Come to this meeting in Portland, Maine. We’re going to take a look at you and see if you qualify.” Well, man, I was pretty scared because I really wanted to be a Riverkeeper. But once I arrived in Portland, pretty much right away I found I had a lot in in common with those people. It was what I’d found I had in common with the Marines I’d served with, some in combat. Here was a group of people so passionate about what they were doing and so committed to protecting their waters that you just knew they were not going to fail. And I knew right then that I had a whole other life ahead of me, with people with absolute integrity, who would fight, who wouldn’t quit, who would stick together, and who would win.

When I went home, I knew that the choice I had made to become a Riverkeeper was the right one. By 1995, we had our answer about the fish kills. Pfiesteria. Pfiesteria, a one-celled animal so tiny 100,000 could fit on the head of a pin was producing a neurotoxin that paralyzed fish and devoured the fish’s blood cells. We also learned what was promoting it.

It was fertilizer pollution, most of it coming from factory swine and poultry facilities. The next seven years on the Neuse River were very trying but now we at least knew who we were fighting. We had as many as 25 cases on our docket every month, and we made tremendous inroads in protecting the Neuse over those years. And today we’ve got two Riverkeepers protecting the river – the Lower Neuse Riverkeeper and the Upper Neuse Riverkeeper.

As I look at the movement that has grown out of that group of people and I look at the Waterkeeper movement today, I know that the seeds that these folks had sown in me are being sown in all of these other Waterkeepers around the world, and that this is a movement that will not fail.

If you’re a polluter and you come across a Waterkeeper, you’re in big trouble. And that pollution will stop. This is a fearsome group of people. I’ve had two major careers, one in the Marine Corps and one in Waterkeeper, and I wouldn’t trade either one for the world.

JP: The first Waterkeeper conference I went to there were just six other Waterkeepers. Casco Baykeeper was the seventh organization in the movement. And when I got back home, I told anyone who would listen that I’d just been with the six most impressive people I’d ever met. Almost 25 years later, I’d say that if you went around this country and you handpicked people who you thought had done the most for the environment, you couldn’t beat these six people. They have set important legal precedents in the field of environmental law and they’ve also saved some of the most important bodies of water in this country, and they still inspire me.

TB: Shortly after I became the Long Island Soundkeeper, I learned that there were 30 to 40 million people within 100 miles of the water body that I had had the nerve to declare myself the protector of. It took me a while to be able to say I’m the Long Island Soundkeeper. It seemed a little pretentious. But once I realized it wasn’t just me, it was all those other Waterkeepers who’ve helped me and given me advice over the years and Bobby Kennedy, Jr., and the legal team at the Pace Environmental Law Clinic, that they’ve all been an integral part of my success, then I was okay with saying I am the Long Island Soundkeeper.

When we all got started, we had a body of law, at least in the U.S., that enabled us to do a lot of things, and we have used those tools, even though there have been continual attempts to weaken them and strip them away, and undermine what they stand for, which is the right of the people to ownership of these resources that we hold in common. Bobby Kennedy, Jr., once said to me, “When you bring these cleanwater cases, you elevate yourself to the status of the Attorney General, because you’re defending the rights of the people who, in our system, are the government.” So we have to be on constant guard for changes in policy rules and law. And it’s even harder in most other parts of the world, in places like Africa and China, where Waterkeepers and other environmental activists have very little law to support them. I’ve never felt that my life was at risk, but I’ve met plenty of Waterkeepers from other parts of the world who are risking their lives for doing what they do.

SB: I think the movement is doing extremely well right now, and I couldn’t be more proud. When I started I was just the second woman, and it was a little tough. You know, a man could speak up. A man could be loud. But I knew that I had to do it in my own Southern way, but do the same kind of work, get the same kinds of results. Now more than a third of the Waterkeepers in the world are women. I see so many young women and people of color in this movement, and I know it’s going to just keep on increasing, and the more diverse we are, the more powerful and effective we’re going to be.

But there’s still a crying need for even more resources. A lot of the times, the polluters we’re up against are very powerful corporations, so powerful that they’ve, in effect, captured the government agencies that are supposed to be enforcing the law. But we have passion and we’ve learned to use the media and the law. And we’ve also become savvy at strengthening each other’s capabilities. I don’t believe there’s ever going to be a time when the Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, and all the world’s other Waterkeeper organizations, won’t be needed. We need to be here tomorrow, next week, ten years, a hundred years from now, because we occupy a space in society between government and the private sector that looks out for the common good in a way that the other sectors never will.

JP: Those of us who were there at the founding, we share a deep kinship. These people are my brothers and sisters. When I talk to some of the Waterkeepers who have been around for two, three, four, five years, and ask, “What did you hear, what helped you the most,” I keep getting the same answer: there was always somebody I could call, someone who I had met at a conference or I saw on the listserv and sounded like they might know something I need. We have this family feeling, and we don’t think about the time and the resources it might take to help someone else. And I think that’s a big part of why this movement is going to keep growing and getting stronger.

TB: I think back to when there were only two of us, me and John Cronin, talking on the banks of the Hudson River. We didn’t call it “waterkeeping” then. And to have seen this grow into more than 270 Waterkeeper organizations working on six continents, I think is amazing. And the core principles, ideas and visions that John and I talked about are still at the heart of the Waterkeeper movement. One of the important functions of having Waterkeeper Alliance is to constantly reinforce those core principles of what it is to be a Waterkeeper, to stand up for this place and this body of water that you love, to stand up for the people who depend on it for their sustenance, in a material and a spiritual way, and to be wholly committed, body and soul, to make a real difference.

We’re different from a lot of the other large environmental organizations because we started as a group of autonomous grassroots organizations that chose to come together because we recognized that we were working toward common ends and that we could be so much stronger if we worked together. It was the Waterkeepers, who were on the water and on the frontlines of the environmental crisis, who created the Alliance not the other way around. And I think that’s grounded the movement in a way that’s deeper and more powerful than any other environmental organization you can think of.

AW: The special feeling that we had in those early days was very heady, because in the short time we’d been Waterkeepers, we had accomplished some pretty significant things. Once we realized just how powerful the Waterkeeper model was, we started to look for ways to multiply what we were accomplishing, and figure out we could act collectively and to share what we were learning. Each one of us brought something to that mix. John was the first to teach us about using the law. Terry had the heritage of being a commercial fisherman. Rick had that we-can’tfail attitude he’d brought with him from his Marine Corps days.

I remember when John Cronin started talking about an international movement, we laughed at him. We called him the “universe keeper.” There were only about a dozen of us at that point, but the Waterkeeper model almost had a momentum of its own, something more powerful than maybe any of us realized.

It turned into what is, as far as I’m concerned, the most successful environmental organization in the world because of the individuals and because it developed organically. It developed with a soul, like many other large organizations don’t have, and it developed into a family, as Sally has said.

RD: There’s one common trait to success, and that’s the readiness and the courage to lead, on the individual level and on the organizational level. From that first meeting all those years ago in Portland, I saw that quality in my fellow Waterkeepers. I knew that they had my back. I knew they always would. I knew they’d come if I needed them. And because of that, I’ve never been afraid of who I was taking on, whether it was a giant corporation or the governor of North Carolina.

Look at Bobby Kennedy, Jr., and his contributions all these years, how he stuck with this movement, how he stuck his neck out for Waterkeepers all over the world. When I meet young Waterkeepers, almost invariably, I sense that same trait, that here’s another leader, people like Nabil Musa in northern Iraq, Liliana Guerero in Colombia, or Mbacke Seck in Senegal. They’re literally putting their lives on the line, but somehow they’re fighting through their fears, and I think a big part of it is that they know that the Waterkeepers around the world have their backs.

Waterkeeper Alliance is solid from the ground up. I’m pretty old now, but I hope I’m around in ten years, because I just can’t wait to see what the Waterkeeper movement becomes. With the track it’s on right now, man, there is just no limit.

TB: I didn’t know how long I would be a Soundkeeper. I figured, give it four or five years and we’d have it licked. It’s been 30 years now and there’s still so much work to be done. And for all that time, Bobby Kennedy, Jr.’s, been a constant in my life and in my struggles, personal and professional. Over those 30 years, we’ve had our share of fights, but through it all we have worked together to make the world a better place for an awful lot of people we don’t know and will never know.

I’ve been a representative in the Connecticut state legislature for almost 25 years, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned it’s that laws are written in pencil. They can be erased. If you’re fighting for clean water, advancing the will of the people that our shared natural resources are protected, you can’t ever let your guard down because it’s a constant fight.

JP: My hope for the Alliance is that we keep recruiting Waterkeepers with the energy and passion to be real catalysts for change in their communities. And I think we will. I also hope that we figure out new ways to help the Waterkeepers who are in countries that don’t have a tradition of philanthropy and don’t have the environmental laws that have been so crucial to the successes of those of us in the U.S.

The Waterkeeper model is there, the success is there, the ethic is there, and I would tell new Waterkeepers be confident and be brave. Follow your instincts, and if you feel it’s right, it most likely is right. Do it. And as Rick has said, know the rest of us will have your back.

SB: I have no doubt that Waterkeeper Alliance will be here in 10, 20, 50 and 100 years. It’s just such a powerful idea that I’m confident that the movement will only keep growing larger and stronger. I think we’re in the first stages of a sea change in human consciousness and that there will be more and more men and women who are committed to speaking truth to power and taking care of the water that sustains all of life.

AW: I think there’s a spiritual aspect to all of this, the web of all living things and our connections to each other. And right from the beginning, Waterkeepers have been the representatives of those who don’t have voices, whose communities and ways of life are being threatened by the powerful, whether in the corporate sector or in government. I would hope that in the coming years organizations with that kind of mission are only going to be more important and more influential in societies in every part of the world.

RD: Waterkeeper Alliance is a pretty awesome organization today; but it’s going to be even more awesome 10, 20, 30 years down the road. I see so many remarkable young people joining this movement. And when you boil it down, it’s really all about individuals. Terry Backer as an individual, Sally Bethea, Andy Willner and Joe Payne. Their commitment, their integrity, their courage. All of the Waterkeepers around the world have got to be outstanding leaders of organizations, but they’ve also got to be outstanding individuals. They speak for the water. And the advice I would give every Waterkeeper is never, ever compromise in your fight for that body of water that you love. No matter who you’re up against, stand your ground and fight for your river, lake or bay. No matter what the consequences are. And if you ever have a question about what it is that you should do, what is the answer to a problem, go down to that body of water, sit on the bank, look out over the water, and ask, “Hey, what would you do if you could speak? What is the answer? What would you want? What do you need?”