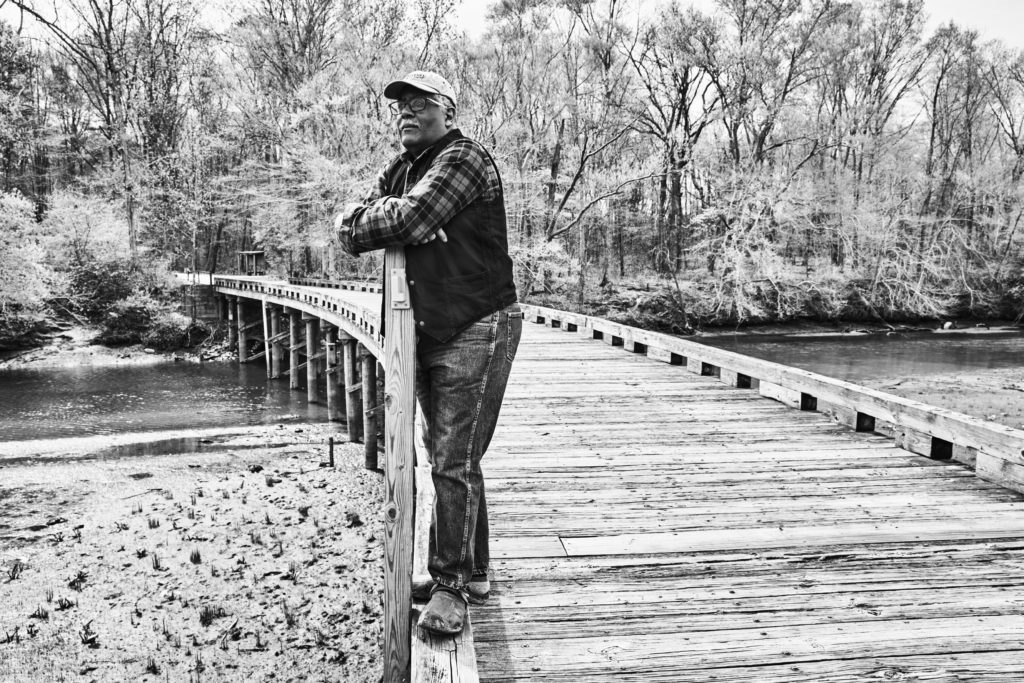

Native Son | Fred Tutman, Patuxent Riverkeeper

By: Tom Quinn

Fred Tutman returned to his “home river” to fight environmental and social injustice.

By Tom Quinn.

Photos by ©Nigel Parry, courtesy of Culture Trip.

The Patuxent River is a tributary of the Chesapeake Bay and the largest and longest river entirely within Maryland. Its 900-square-mile watershed is also the largest completely within the state, extending into seven counties. The river lies between the Patapsco River to the northeast, which passes through Baltimore, and the Potomac to the southwest, which passes through Washington. It is home to more than 100 species of fish, including bass, catfish, chain pickerel, and bluefish.

“This is a nice compact river, but it has the deepest water in the Chesapeake region,” Fred Tutman, the Patuxent Riverkeeper, says. “It reaches a depth of 190 feet in the lower Patuxent.”

Fred’s love for the river runs just as deep.

Patuxent Riverkeeper’s office is located in Upper Marlboro in Prince George’s County, where Fred was born and raised, along the Patuxent, as were seven generations of his ancestors. He still lives on the farm where he grew up. For him the river has always been “a spiritual talisman of his farm upbringing” and life in rural southern Maryland.

“The river was our playground as kids,” he recalls. “It was where we got food. My family watered their crops from this river. My great-grandfather farmed tobacco and other crops, and fished for yellow perch there. In every respect, as much as I’ve lived in other places and enjoyed other rivers, the Patuxent is very much my home river.”

As a five-year-old he was the first black child to integrate the kindergarten he attended in Upper Marlboro in the early 1960s. He remembers that some white parents took their children out of the school because of it.

Behind the school there was a pond that emptied into the Patuxent.

“I remember I used to look out the window at that wetland,” he says, “and think about how much more interesting it would be to be out there than in that musty old classroom.”

When he was a teenager his father became a director in the Peace Corps, and Fred moved with his parents and two sisters to Sierra Leone in West Africa. They spent two years there and a year in Tanzania. “My early interest in water was sparked by riding river boats up the rural inland waterways where goods, people and livestock were ferried along river byways that were centuries old,” Fred says. “They were the lifeblood of these isolated communities.”

After college, Fred spent more than 25 years as a journalist, working in radio, video, films, and satellite communications.

“I covered news stories internationally for U.S., British, and Canadian news organizations, on a contract basis,” he says. “I worked around the world with CBS, ITN, CNN, and BBC, among others. I had an office in Rome and covered the Falklands War in the mid-1980s. I also ran a project for the Ford Foundation in West Africa.”

But he always returned to the farm, and finally he got tired of all the travel – “and of reporting about all the things that were wrong with the world. I came to the conclusion that it was time to start focusing on finding ways to make things better.” He decided to attend law school. In his third year he was at a meeting at the Maryland Department of the Environment, when “this guy walks into the room that has this incredible charisma and stage presence and he says his name is Fred Kelly, and he’s the Severn Riverkeeper, and I thought, wow, this guy’s got something going on. I’d never heard of a Riverkeeper before.” Fred decided to read Bobby Kennedy, Jr. and John Cronin’s book, “The Riverkeepers.” “I was completely blown away,” he says. “These underdogs were taking on government bureaucrats and powerful corporate polluters and they were winning. That seemed like such a huge thing – these Waterkeepers who were sort of water-quality guerillas unafraid to stand up to a woefully inadequate water-protection system!”

That’s when he decided to take on the job of fighting for the river that was so close to his heart and heritage. “But I also saw it as a medium for making a better and more just society by fighting for something as essential as people’s right to clean water,” he says.” He founded Patuxent Riverkeeper in 2004.

Fred is proud that the Patuxent inspired a long history of activism. In fact, it was the first river in Maryland that the state was forced to clean up under the Clean Water Act. In the early 1970s, Calvert County Commissioner Bernie Fowler and county executives from Charles and St. Mary’s counties filed several lawsuits arguing that the EPA was allowing sewage-treatment plants in upriver counties to discharge too much waste into the river. And they won those lawsuits.

Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay Program ultimately came about because of the activism on the Patuxent, according to Fred. “Bernie and those other early activists lit the fuse and citizens on other rivers followed in their tracks,” he says. “I’ve always believed that it’s our job at Patuxent Riverkeeper to keep that fuse lit.”

A lot of Fred’s work has been in the field known as “environmental justice,” which he prefers to call “environmental injustice.”

“When you say the words ‘environmental justice,’” he argues, “most people think you are talking only about black folks or people of color. We see it in a much more expansive sense. These are usually David and Goliath class-based fights where people with far less power are largely fighting people with an exorbitant amount of power and money. And that can be a white, black, Native American, Latino, or Asian community – any community except a rich community. You don’t find many rich white communities fighting off coal-fired power plants or factory farms or sewage discharges. Those, frankly, are placed where there is less money and less power, and the two seem to go together.”

He describes Patuxent Riverkeeper as “part of a social activist movement where the environment is key. The way I see it, we are community organizers where our community is defined by the track of the river.”

“You don’t find many rich white communities fighting off coal-fired power plants or factory farms or sewage discharges. Those, frankly, are placed where there is less money and less power, and the two seem to go together.”

His favored approach is “to listen to what folks need and start helping exactly where they are – by taking our cues from the grassroots. It doesn’t have to be staffed out and it doesn’t take a lot of material. It’s all about having the willingness to listen, help and the spine to stand up for what’s right and fight.”

One of the prime examples of this has been his work with Eagle Harbor, one of Maryland’s smallest municipalities, which sits along the Patuxent in southernmost Prince George’s County.

“This town has been steeped in a legacy of racism and injustice since its founding,” Fred says, explaining that in the 1800s part of the town was a steamboat-landing site that transported slaves who worked the Maryland tobacco fields. In the 1920s, when people of color were barred from beaches in the area, black residents from the Washington vicinity formed Eagle Harbor as an enclave and resort.

“Like many places in our watershed,” says Fred, “the environmental problems that exist there now were shaped by the legacy of past disparities and injustices, and have their roots in racism and hardship. Pretending that the shortfall in public investment at Eagle Harbor is just circumstance or lack of ‘environmental literacy,’ is crazy, and no Riverkeeper could get anywhere by pretending the same solutions would work here as they would in a white suburban neighborhood sitting on the bay.”

In the 1960s, the massive Chalk Point coal-burning power plant, one of Maryland’s largest, was built just south of Eagle Harbor. The plant is, by far, the leading polluter in Prince George’s County, and has been guilty of numerous unlawful discharges and other violations. Fred believes the siting of the plant next to this small African-American community was no accident.

“Just acknowledging the past context and present reality helps us connect to and serve this town,” Fred says. “But we would fight just as hard for any community, of any ethnicity. In some ways, Patuxent Riverkeeper is a cross-cultural bridge between the have and the have-nots in this watershed, fighting some of the most controversial battles and, frankly, the hardest to fund.”

He first identified some open questions at Eagle Harbor, such as how direct discharges to the river could be contaminating fish and crabs, and how the plant was making enormous freshwater drawdowns from the same aquifer as the town, which could adversely affect the quantity and quality of their water. But despite residents’ concern about Chalk Point they were reluctant to confront them because of the lopsided power dynamic. “There were some fights we were ready to fight through litigation that they were disinclined to take on because they lacked the political or financial resources,” Fred says.

“It was Fred who opened our eyes to pollution and environmental issues in general,” says Eagle Harbor Mayor James Crudup. “Before Fred we didn’t have anyone that we could turn to and find out what was going on in regard to the town’s waterfront. Recently he was very instrumental in our receiving grants from the Department of Environmental Resources, including a $100,000 grant to help creek flooding and erosion. Fred is my go-to-guy in regard to our environment. We’d be in a very different place without him.”

In 2015, the plant’s owner, NRG energy, announced plans to reduce discharges from a plant it owned along the nearby Potomac River and increase them along the Patuxent in a “pollution trade.” It was not the first time Fred decided to sue, but it was the most likely way to protect the river and the town from a gross inequity.

“It wasn’t an easy decision to make, because it meant walking away from a funder who disagreed with our stance on pollution trading – but I had to,” Fred says.

Ultimately, the company abandoned the idea of the trade. Since then, Patuxent Riverkeeper has filed several legal actions against the company for exceeding its discharge limits. Fred has also helped the town secure grants to improve a waterfront park and develop a comprehensive plan for its future.

On April 26, Fred received an award for his outstanding service to Eagle Harbor at the town’s 90th anniversary celebration. “Our conversations with towns like Eagle Harbor almost always start with us trying to determine what their needs are,” Fred says. “James Crudup and the Eagle Harbor Town Council had a vision for bringing some new growth to the town. For example, they told me they wanted solar panels. So, I called some people I know that are familiar with solar panels. Now we’re trying to put a deal together for the town and responding to what the community’s vision is.”

Fred was also able to connect them to another African-American community, Highland Beach, which exchanged helpful information on how they had obtained solar panels. “In a sense, we are building a far-flung sense of community around water and environment,” he says.

Over the years, Patuxent Riverkeeper has litigated 19 cases. Twelve of those made it to trial and the organization prevailed in eight of those suits, and grossed nearly a half-billion dollars in judicial penalties, fines and reparations from polluters. One of the victories he is proudest of occurred this year. It resulted in the closing of the Brandywine coal-waste disposal site, rated recently as the seventh worst in the nation in a report by the Environmental Integrity Project, which stated that “ash from three NRG coal plants has contaminated groundwater with unsafe levels of at least eight pollutants, including lithium, at more than 200 times above safe levels, and molybdenum, at more than 100 times higher than safe levels. The contaminated groundwater at this site is now feeding into and polluting local streams.”

In his latest annual letter to members, Fred wrote, “Two of our board members, Dr. Hank Cole and Dr. Sacoby Wilson, were instrumental in testifying, framing our legal and activist strategy, and bringing home this victory that will give relief to the river and to the surrounding community after 44 years of what had originally been a ‘temporary’ special exception when first approved in the 1970s.”

The closing of the Brandywine coal-ash site may also have an added bonus, profoundly affecting the quality of life and the future prospects in Eagle Harbor.

The Chalk Point power plant’s coal waste was trucked to Brandywine, which is only about 18 miles from the plant. “Now NRG has to ship it to a site out of state, in West Virginia,” Fred says, “and they claim it’s costing well over $100,000 a month.”

NRG already has declared bankruptcy. “It will surprise the hell out of me if it closed,” he says. “Some company will come along and figure out how the plant can still be a cash-cow. But the odds are this plant cannot stay within the law for long due to its outmoded design.”

Fred has been the Patuxent Riverkeeper for 15 years now and it’s been a job, he says, that he loves more than any other in his long and varied career. “I wasn’t bad as a TV producer, but near the end my heart was no longer in it. I love working with these communities, where I can plant seeds that will last for a lot longer than any TV or radio show I ever produced.”

But over the years, he has had five separate heart-related medical procedures, culminating in a double-bypass surgery a little more than a year ago. “This work has never been easy, and it isn’t getting any easier,” he says. “What I’ve tried to do is to create a watershed protection movement that is truly representative of the hearts, minds and souls of the very diverse people and communities along the Patuxent River corridor. But now it’s time to put together a succession plan, which we probably should have done a while ago.”

“This work has never been easy, and it isn’t getting any easier.”

In the annual letter he wrote, “Frankly, for a guy like me in his 60s with a very busy work career behind me, heart disease potentially lurks in nearly every one of these lawsuits, river campaigns and the continuing struggle…”

He knows the way forward is to build on what Patuxent Riverkeeper has accomplished in its first 15 years. And he also knows that, personally, it won’t be easy to retire from the Waterkeeper movement, and he’s passionate about why. Not long ago, he wrote this:

“The honest to goodness truth is that it was the ‘jazz’ in this movement that grabbed me in the first place. It was in 2003, when I heard Bobby Kennedy, Jr. give a speech about how ‘God’ speaks to us in Nature in nearly every faith and every tongue.

“To me jazz fits the entire scheme of nature in the sense that it is syncopated, organic to its setting, improvised and unscripted, has multiple themes and voices, is capable of inciting and inspiring great passion and meaning.

“That, to me, pretty much described the diverse, grassroots and inclusive spirit of this Waterkeeper movement – at least as I saw its potential. Here, I thought was a movement where Jazz would be welcomed just as much as Classical, Bluegrass and virtually every other style of music. I still believe that is true.

“Every shade, facet and aspect of the human spiritual experience is embodied within our very human scale and heartfelt connections to sacred water. But if God is on our waterways (whichever God you endorse), then surely (to quote James McBride) he/she is the color of water and so is our movement.”

Tom Quinn is the Senior Editor at Waterkeeper Alliance and the Editor of Waterkeeper Magazine.