Picturing the Sundarbans, a Region in Crisis

By: ajcarapella

Photos and text by Lynne Buchanan

The Sundarbans (translated from Bengali as “beautiful forest) is a region along the Bay of Bengal in India and Bangladesh that spans thousands of square miles of land and water, and includes the world’s largest contiguous mangrove forest. Recognized by UNESCO for its “Outstanding Universal Value,” its biological diversity and the ecosystem services it provides, part of the Sundarbans that lies in Bangladesh was designated as a World Heritage Site in 1997, a decade after the Indian area received the same designation.

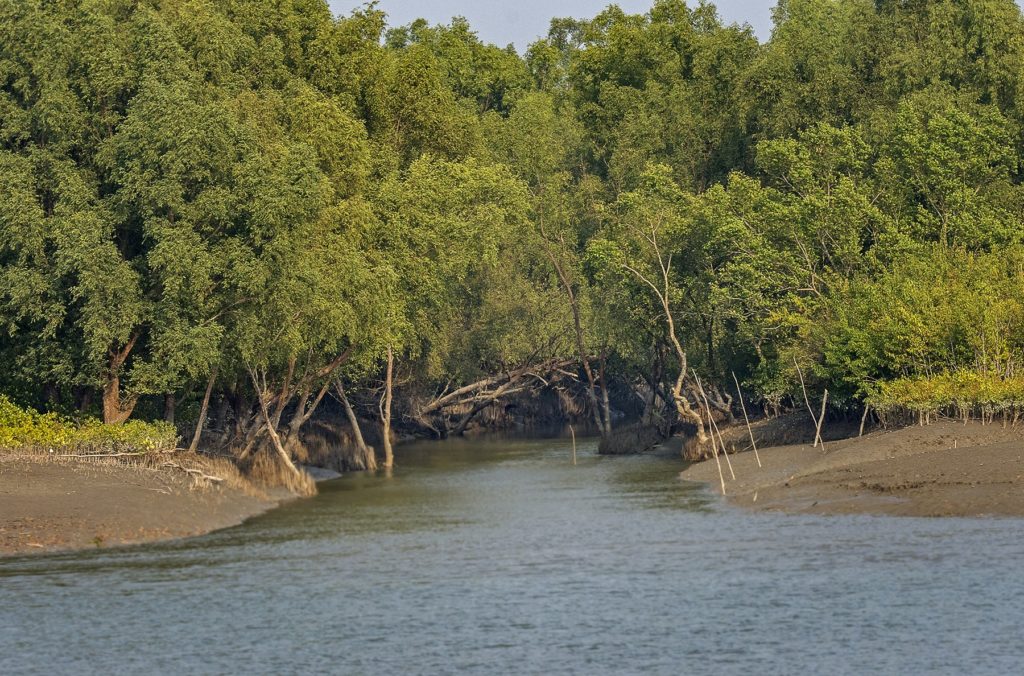

The image above shows one of the many mangrove tunnels that grace the approximately 200 islands in the Sundarbans. But rising sea levels are causing these islands to disappear, which is happening here faster than almost any other place in the world. Indeed, some scientists believe the Bay of Bengal is rising twice as fast as other water bodies, and have predicted that the entire Sundarbans could be under water in 15-to-25 years.

Located in the world’s largest natural delta, which is formed by the basins of the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna Rivers, the Sundarbans are home to 334 species of saltwater-tolerant trees and 269 species of wild creatures, including Royal Bengal tigers, Ganges River dolphins, and crocodiles. In 2015 it was estimated that eight million people lived in or near the Bangladesh side of the Sundarbans, while five million lived in or near the Indian side. Eighty percent of the people depend on fishing for their livelihoods, but the ecosystems that support this industry are threatened by climate change, cyclones, deforestation, increased salinity, oil- and coal-spills, pollution from rivers that flow into the delta, and reduced flow resulting from dams and grabs of fresh water by India.

But the most serious threat to the Sundarbans’ survival is the proposed 1320-megawatt Rampal power plant now under construction in Bangladesh, which would burn five million tons of coal a year that would have to be transported through this delicate ecosystem. “If the Rampal coal plant is built, it will require hundreds more coal ships and barges to travel through the Sundarbans,” my host Sharif Jamil, who is the Buriganga Riverkeeper and coordinator of Waterkeepers Bangladesh, told me.

According to government officials, the plant is projected to come online by 2019. Environmentalists are also concerned that the plant will draw its water from the Passur River, a lifeline to the Sundarbans, and will discharge wastewater back into that same river. They believe this will threaten the viability of the mangroves, which act as an important “carbon sink” – an absorber of carbon dioxide – for the entire planet.

Boats at the fishing village of Dublar Char in the Sundarbans

In addition to polluted water from coal-ash ponds, the Rampal plant would cause severe air-pollution that would contribute to global warming and affect the health of people, trees, and ecosystems. The Daily Star in Bangladesh has reported that this pollution would “cover the entire Sundarbans ecosystem, Satkhira, Khulna, Noakhali, Comilla, Narsingdi and Dhaka districts in Bangladesh and Ashoknagar, Kalyangar, Basirhat and Kolkata of West Bengal.” The all but unbreathable air in Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital city, would become even worse. Nasrul Islam, in his book Bangladesh Environment Movement, History, Achievements and Challenges, states that Dhaka has been described as “a gas chamber for slow poisoning,” and reports that it is destroying the bodies and brains of its citizens, especially children. (I can attest that this is true because one sweltering day in the district I almost succumbed to carbon-monoxide poisoning.)

A Greenpeace study found that the plant would cause “at least 6,000 premature deaths and low birth-weights of 24,000 babies during its 40-year life.” UNESCO has recommended immediate cancellation of the Rampal project.

Removing coal from the Shela River

In May 2016, a bulk-cargo vessel carrying 1,245 metric tons of coal sank in the Shela River, which also runs through the Sundarbans. It was the fourth incident in two years. The image above shows that, almost two years later, coal is still being cleaned up at the site.

Sharif Jamil addresses the fishermen of Dublar Char

Given that the Sundarbans are located in the world’s largest delta, it is no surprise that fishing is the principal means of livelihood. Additionally, the region provides food security for much of Bangladesh, among the most densely populated countries in the world, because many of its rivers, especially those around Dhaka, are so polluted that their fisheries have been destroyed.

During my trip to the Sundarbans, Sharif Jamil took me to visit the Dublar Char fishing village. It was almost dusk when we arrived and I was struck by the incredible beauty and peacefulness of the scene. I could see why people in other parts of the country would come here for five months of the year to fish, despite the dangers they face from man-eating tigers and crocodiles. Sharif spoke to a gathering of about 3,000 fishermen about the Rampal plant and its threat to their livelihoods. He spoke with them about their rights and the actions Waterkeepers Bangladesh was taking to oppose the plant. “We are beside you in this fight,” he said.

Rinsing small fish to make chapa shuntki

From late October until the monsoons come in April, the fishermen collect and dry fish to make the fermented product chapa shuntki. After being rinsed, the fish are dried and then sorted. Polluted water has reduced the size of the fish, which are an essential food source for 165 million people.

Fresh tiger tracks along a narrow canal in the Sundarbans

The Royal Bengal tiger has been on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species since 2010, and a 2015 census showed that the population in Bangladesh was down to 106 from 440 in 2004. The nation’s forestry department is currently undertaking another census lasting two years. Because the presence of tigers discouraged fishermen from entering the dense forests, they helped protect the mangroves, but increased salinity and flooding is now forcing the fishermen deeper into the Sundarbans, threatening the survival of both mangroves and tigers.

Reduced flow along the Padma River

The above image, taken at the end of February, roughly a month before the start of monsoon season, shows a shrinking stream in the Sundarbans UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Trucks heading to the Rampal power plant construction-site

The image above was taken just before the scheduled start of construction of the Rampal power plant in March. Bangladesh and India are jointly undertaking the $1.7 billion project, slated to be completed by 2019-20. It is estimated that the plant could produce 38 million tons of highly toxic coal ash over the course of its operational life.

Lynne Buchanan is a fine art photographer who specializes in work on the environment. Her book, Florida’s Changing Waters: A Beautiful World in Peril, will be published by George F. Thompson Publishing in 2019.