Healing Waters

By: Carol Parenzan

Six Pennsylvania inmates learn to look at the natural world like a Waterkeeper, and to change their lives in the process.

By Carol Parenzan, Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper

The six prisoners stepped uncertainly out of the non-descript white van. They were young men, clad in brown-and-red work clothes and wearing freshly polished military-style boots. They told me later they didn’t know what to expect, and, to be honest, neither did I.

We were in the Pennsylvania Wilds, a sparsely populated part of the Susquehanna River watershed comprising two million acres of public forests, and home to some of the most spectacular wild lands east of the Mississippi. They would be staying six months, as residents of the state Department of Correction’s military-style Quehanna Boot Camp, where they would be subject to strict discipline and the shrill shouts of drill instructors. It appears an unlikely place for rebirth, but Corrections’ staff gamble that most boot-camp inmates have the capacity to change their behavior for the better.

“A healthy river is much like freedom. Easy to lose. Harder to get back.”

– an inmate, Quehanna Boot Camp Watershed Steward Prison Project

At this isolated facility there are no fences, no barbed wire, and no guards with guns staged on high towers. Instead, there are swaths of birch trees, abundant wildlife, a canopy of red pine, an understory of ferns and wildflowers, free-running streams, and large, domineering elk, brought here in an attempt to recover the species that was once native to the land. The recovery was succeeding. They had been given a second chance.

“Good morning,” I said, keenly aware that I was wearing badly scuffed hiking boots that were in need of a good polishing. “I am Carol Parenzan, your Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper. I don’t expect you to know what that means just yet, but by the end of the week you’ll have a better understanding of what I do and how each of you can help me and other Waterkeepers be protectors of our streams and rivers.”

I was met with blank stares.

“You’re not here with me to be my workhorses,” I continued. “I won’t ask you to do anything I wouldn’t do, too. We are partners for the next five days. The only difference between you and me is that I haven’t made that one bad decision – yet.”

A smile. A grin. A nod of the head. Six bodies relaxed just a bit.

“Yes, ma’am,” they replied in unison.

They had arrived here from various places. Two called the Philadelphia area home. Two were from Pittsburgh. One said he was headed to Arizona after his release, and the last was planning to return home to North Carolina. Two of the six had never dipped their toes in freshwater. Not a stream, not a lake, not a river. Rivers and streams were not their friends. They were from the city; freely flowing water was foreign to them. They feared what they did not know.

It was time to put them at ease: “Our rivers can only be as healthy as the land that surrounds them,” I said. “Today, we’re going to start by discovering the meadows and forests around us.”

Their eyes seemed fearful as they swatted away pestering gnats that were drawn to their deep exhales. What about those elk? Bears? Coyotes? Poisonous snakes? Biting spiders? Ticks carrying disease? We would have to help them find their comfort zones before we could begin to address concerns in the watershed.

As a group we walked briskly toward a shelter where we would set up a week-long class and begin our discovery. Each prisoner was handed a blank journal and asked to write his initial thoughts about what he expected. That evening I and Tina Hayes, the young AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer who was working with me, would read their entries to better prepare us for the remainder of the week.

We began with an exercise called “one small square,” in which we would focus our observations on a one-squarefoot grassy area near the shelter. After about ten minutes, I asked, “What do you see?” As I had expected, having conducted a similar exercise with other kinds of groups, their responses were sparse. It was time to nudge them a bit, give them permission to stretch.

“Let’s observe these same spots for another ten minutes,” I said. “This time, don’t be afraid to look a little closer, move grass blades out of the way, and place your face just inches from your square area. Get comfortable. Lie on your bellies. Really get in there and look.”

In just a few seconds, voices rose, reporting that an ant was carrying a chewed piece of leaf, that they noticed some scat (although the observer had another name for it), some dispersed seeds, a dropped berry, a footprint, and more. They were taking baby steps in military boots.

“You’re becoming scientists!” I proclaimed. “We have a special term for individuals like you – citizen scientists, and citizen scientists play a critical role in the work that Waterkeepers do.”

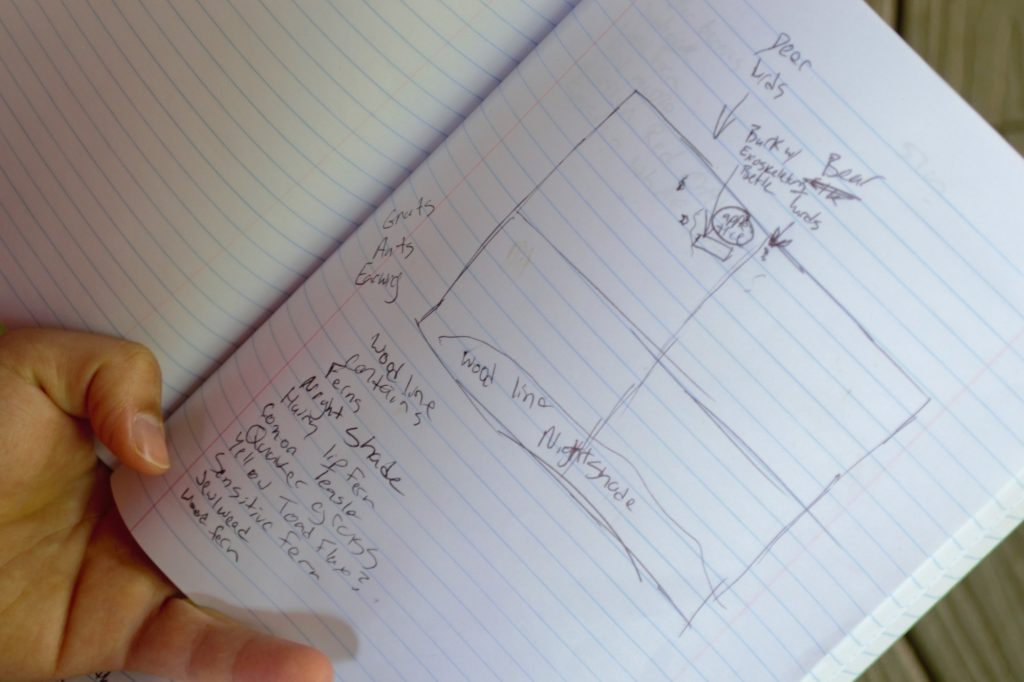

We headed back under the shelter. I distributed my nature guides – small books and laminated foldouts that dealt with tracks, scat, birds, insects, wildflowers, trees, waterfowl, weeds, and more. They enthusiastically explored the guides, attempting to identify what they had observed, and they recorded their findings with words and drawings in their journals. We repeated this exercise in a nearby meadow, and again in the woods. As they continued to record their observations, their confidence grew, their notes became more detailed, and their identifications more exact. They were indeed becoming citizen scientists.

“You’re becoming scientists! We have a special term for individuals like you – citizen scientists, and citizen scientists play a critical role in the work that Waterkeepers do.”

It was time for lunch. “I’m going to slip away during the lunch break,” I announced, wondering where they thought I might be headed. “When I return, I’ll have a surprise with me. We need it for our afternoon session, which I think you’ll enjoy.” I wound my way through the mountain terrain along ripples and rapids to the cottage we were calling home for the week. When I returned by car to our worksite, I found six sets of guarded but curious eyes watching me carefully as I opened the back passenger door. Out jumped a young Chesapeake-red, long-haired Nova Scotia Duck Toller. “Meet Susquehanna,” I said. Five of the six surrounded the dog, and with permission, affectionately scratched and pet this 35-pound ball of energy. I assured the one unengaged member of the group that he could simply observe. Here, perhaps, was another fear to overcome.

The inmates used nature guides that covered everything from animals tracks and scat to wildflowers, trees, waterfowl, and weeds. Photos by Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association, Inc.

Susquehanna, also known as Suss or Sussey, is the “conservation canine” for Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association. He is being trained to detect sewage leaks throughout the watershed, working with me on a consulting team contracted to municipalities, engineering firms and even other Waterkeeper Organizations to investigate stormwater systems, runoff, septic fields, and manholes in search of that troubling scent of sewage.

Over the next two hours, the prisoners took part in Susquehanna’s training by hiding scent-boxes and working with Susquehanna to find them. I stepped back. They stepped in – all of them, including the hesitant one. They were functioning as a team.

All week long, after working mornings on the kinds of skills required of a Waterkeeper, we would take Sussey for long training walks in the afternoon and practice our observation skills. And before we left each of the five worksites, we would conduct a garbage sweep and leave those spots cleaner than we’d found them. As the week progressed, our observation squares became larger, closer to water, then in water, and these fledgling citizen scientists began to learn about tree-mapping and sizing, water chemistry and testing procedures, collecting and identifying macro invertebrates, and much more.

They began to appreciate the deep connections between land and water and understand the human influence on both. Having begun by examining a small square, they advanced to observing a small watershed, and spent their final day studying a creek that had been affected by a tributary tainted by drainage from an abandoned mine and a small wastewater-treatment plant. The team’s confidence grew. Those members who had feared working in and around water now sat on rocks in the middle of the Susquehanna River, writing in their journals. They were proud of what they’d accomplished, and so were their mentors. The seeds we had planted were yielding fruit. Before long, I hoped, they would return to their communities and become spokesmen and advocates for their home waters.

“They began to appreciate the deep connections between land and water, and understand the human influence on both.”

In August we will go back to the Pennsylvania Wilds to work with six new residents at Quehanna Boot Camp, and Sussey will find new hands to train him. Our plans are someday to enhance this experiential learning program with a green-jobs fair for all the inmates at the correctional facility, and then to create an “ecopreneurship” program for inmates beyond Quehanna Boot Camp but within the Susquehanna watershed. Finding a job after incarceration is a daunting challenge, and we hope to provide mentorships in which prisoners can explore and develop green-business ideas, focusing their minds during incarceration and offering hope for their lives afterward.

Over the course of the week, the six young men learned the kinds of skills required of a Waterkeeper, from map reading to water sampling. Photos by Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association Inc.

I extend my appreciation to several people and organizations that enabled us to launch the Quehanna Boot Camp Watershed Steward Prison Project. Thank you to the staff at the camp and the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections – for your trust. To Melinda Hughes and her organization, “Nature Abounds” – for assisting with stream-assessment skills. To Tina Hayes, our AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer – for taking thousands of photos during the week for us to select from. To the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of the Susquehanna Valley – for financially supporting our week in the Wilds. And, surely – to the six young-adult residents for having the courage to begin to change their lives, and mine as well.