Saving the Wild Karnali

By: Gary Wockner

Story and photos by Gary Wockner, Poudre Waterkeeper

In the shadow of a massive dam proposal, Nepal’s Waterkeepers take to the water to save Nepal’s last wild river.

Megh Ale (pronounced “Ah-lay”) is a patient man. His eyes twinkle, the corners of his mouth almost always turned up into a soft smile. He was a monk before he started his rafting, adventure travel, and river conservation endeavors. Patience is a virtue in Nepal if you are a river conservationist. But a sense of alarm is also there in Ale’s face and voice. Nepal has about 6,000 rivers and streams, and every single river is dammed, except one. That’s right — one.

Now, that final free-flowing river, the Karnali, is also threatened, and Ale is trying to save it.

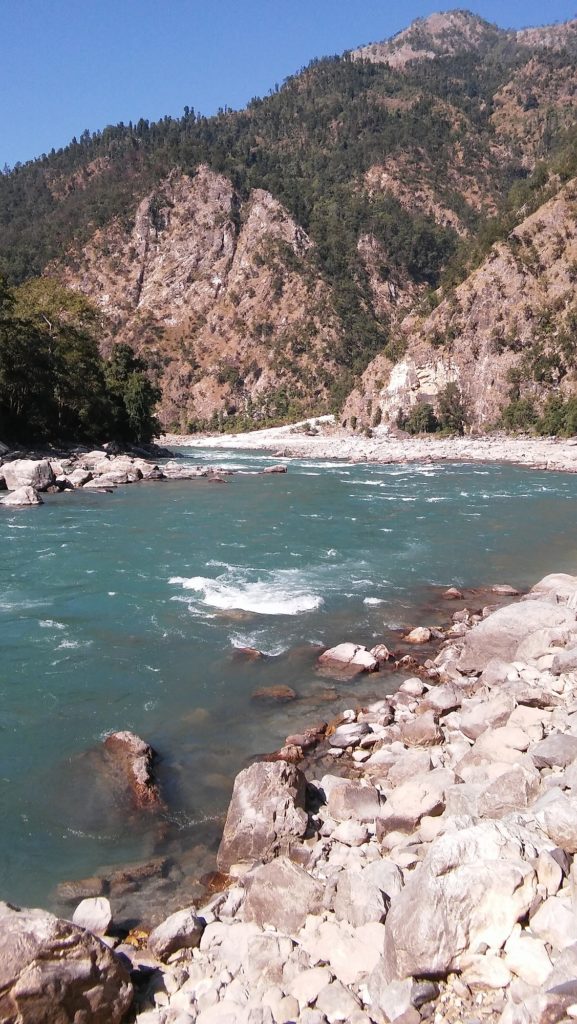

The Karnali River begins in the Himalaya Mountains in Nepal near the Tibet border and Mt. Kailish, the spiritual center for four eastern religions − Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Bon. The mountain is believed to be where the Hindu Lord Shiva sits in a state of perpetual meditation. In bold contrast, the Karnali is never still. It rages down the canyons of western Nepal, its glacier-fed blue-green waters glistening in the sun.

In the first week of last November, which is the dry season in Nepal, Ale and his team from the rafting company he owns, Ultimate Descents, led 21 international adventurers from 10 different countries on an eight-day trip on the Karnali. Our expedition was the inaugural “Karnali River Waterkeeper Expedition,” and wasn’t only about rafting. Organized in cooperation with the Nepal River Conservation Trust, which Ale co-founded in 1995, and Waterkeeper Alliance, which Ale joined in 2016 as the Karnali River Waterkeeper, this journey was dedicated to protecting the Karnali.

On our first day at the put-in (the starting point for the rafting trip), five of us awoke early and drove 18 miles upstream to the proposed site of the Upper Karnali River Dam in the village of Daab. GMR, a private Indian engineering firm that is named for its founder, G. M. Rao, plans to build the 520-foot-tall hydroelectric facility there. The company has built a small headquarters in Daab, their six modern buildings contrasting dramatically with the traditional mud and slash-roofed homes of the villagers.

The GMR project is just one of several proposals to dam the Karnali, including a competing Nepal-government plan for a 1,345-foot dam that would be the world’s tallest. These proposals have ignited a massive controversy in Nepal and have increasingly drawn international attention from activists and media.

Quickly after arriving, four of us snuck down through the village to the bank of the river and unveiled a “SAVE THE KARNALI” banner that proclaimed, “The last best place in Nepal and only free flowing river in the country.” We photographed the event and returned to our trip’s starting-point at the village of Sauli, which would be the last large settlement we’d see for eight days – and the street where we parked our bus would be the last road. Most of the canyon downstream from Sauli is dotted with small farming villages accessible only on foot.

We quickly eased into the water, and left the village and the bus behind us. As our armada of three large rafts and three kayaks set off, I could see the blade of my paddle through the Karnali’s blue-green water, which is clear down to about six feet, then becomes clouded by the dissolved minerals running off the Himalayan glaciers.

We estimated the river’s flow at this point to be 20,000 cubic feet per second, which is probably one-fifth what it would be during the wet season in June, July, and August, when the monsoons drench the entire country. The following three months are the year’s driest and sunniest, and now the high watermark of the river could be seen 10 feet above us, below which the banks had been scoured clean of vegetation and most debris. It is water at that top level that the dam companies are hoping to divert and harness to generate electricity.

Although the financial, political, and ecological details have yet to be worked out, GMR plans to build what’s called a “run of the river” hydroelectric project, which would divert almost all of the water out of the river, bore a massive two-kilometer-long tunnel down through a mountain, place a powerhouse at the tunnel’s bottom, then run the water back into the river 44 miles downstream with the result that those 44 miles of river would be virtually drained dry. Because the Karnali makes a long circling switchback in the proposed area of the dam, the project would maximize the power created by the fall in the river, while minimizing the length of the tunnel, thereby creating a relatively cheap source of electricity.

All of the dam proposals for the Karnali have been delayed for two decades due to politics and competition among the proposals, including the Nepal government’s proposal to build the world’s largest dam and to maintain ownership of the project and the electricity. The GMR proposal took a step forward in 2014 when the company reached an agreement with the government. The proposal calls for shipping 75 percent of the electricity to India. But the project has stalled for lack of both funding and political support. Facing a projected cost of nearly a billion dollars, the project’s backers have sought financing from the World Bank and other international lending agencies, which has not yet materialized.

A countering proposal is to keep the Karnali free-flowing as the only protected river in Nepal and a source of conservation, pride, and eco-tourism for its people. The country’s nascent river-protection movement, led in part by Megh Ale and his colleagues, has the strongest voice in this controversy, and has brought together members of the country’s many religious and ethnic groups. Ale is working to build a national campaign to produce legislation similar to the U.S.’s National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, to protect the Karnali River and its corridor that extends from the Chinese border, through Nepal and down into India.

It was this proposal that was on our minds as we paddled and floated past several small villages during the first few days of the expedition, becoming increasingly aware that the river is not only a priceless ecological treasure, but is home to unique and endangered indigenous communities as well. One memorable scene developed as we approached a moderate-sized rapid around a large bend in the river. A funeral pyre burned brightly on the bank, surrounded by about 50 people holding candles.

Ale had told us when we started out that we might see Raute people, Nepal’s last nomadic tribe. Small bands of the tribe live as hunter-gatherers in the forest surrounding the Karnali. On the fourth day of our expedition, as we set up our tents at a place called Scorpion Beach, two Raute walked out of the forest to visit us. Their dialect overlaps with the Nepali language, so Ale and the Nepali guides and rafters who were with us were able to talk with them.

Over the next 24 hours, a few dozen Raute members came into our camp; then we accompanied them to their makeshift village where they were living in huts made of branches covered with tarpaulin. They subsist by harvesting large tuni trees, whose rich dark wood they carve into bowls, boxes and stools that they trade to Nepali villagers and occasional tourists. The Nepal government has granted the Raute privileges to cut down these big, beautiful trees, which are otherwise protected. Our cultural exchange included buying some bowls and taking the Raute chief for his first-ever ride in a raft.

As we continued down the river, we regularly came across villages carved out of the forest every few miles. Their inhabitants have been thriving there for hundreds of years by fishing, farming rice and vegetables, and selling and trading other goods when they hiked out of the canyon. The villages’ residents sold us fish and vegetables, and, at one point, a goat, which we slaughtered and ate over the next two days. We often encountered villagers in long dugout canoes, paddling along the edges of the river and ferrying themselves and products from bank to bank across its calmer stretches. We occasionally saw people slipping through the forest above us, sometimes walking down to the beach to say hello, sometimes not.

While the human culture along the Karnali may be several hundred years old, the geology of the river and the canyon has been forming for millions of years. For an unforgettable two-day stretch, we ran through a steep-walled canyon of hard rock that created fabulous rapids. We scouted then raced through “class III” and “class IV” rapids named “Sweetness and Light,” “Jailhouse Rock,” “God’s House,” “Juicer,” and “Flip and Strip.” Although GMR’s proposed dam, tunnel and powerhouse are upstream of this wild section of the river, the rapids would nonetheless be diminished by the hydropower project. And the wonderful beaches that line the river banks would be even more diminished − the dam would trap all of the sand and sediment upriver and over time would rob the beaches in the lower river of their sand, just as dams do all over the planet. The dam also would block the passage of endangered migrating fish, including the mahseer, which can grow five feet long and weigh over 100 pounds, and the giant catfish, which can be even bigger. And it would further endanger these fish, the human culture that survives on the fish, as well as the river’s burgeoning eco-tourist economy.

Three raft companies currently run a few multi-day expeditions on the river each year. One of our crewmates, Ramesh Bhusal, a journalist who also works with Waterkeeper Alliance along another Nepali river, stated his belief that the eco-tourist economy has great potential to expand and provide more sustainable jobs than the hydropower project.

Megh Ale takes this idea a step further; he foresees a “Karnali River National Park” that would protect not only the river, but also a mile-wide corridor all the way along its route from Mt. Kailish on the Tibetan border, down into Bardia National Park in Nepal, and through Nepal into India to the headwaters of the Ganges. Although the country contains many national parks and spends vast amounts of money to protect them and their wildlife, it has no protected rivers.

As our expedition ended on the eighth day, we floated out into the plains at the town of Chisapani, where the river widens before braiding downstream, and where large diversion structures already suck out water to supply the massive rice farms on the plains. So the Karnali River remains undammed, but not untouched.

Plans to keep it undammed are gaining steam through efforts to reach out to international funding agencies, media and political leaders, and to further develop the eco-tourism economy of rafting and fishing. Amid massive mountains and glaciers that fascinate the world, the beautiful Karnali still runs free and begs to be saved, and Ale and his team are digging in for the adventure of doing so. W

An earlier version of this article previously appeared in the online Earth Island Journal.

Gary Wockner, PhD, is the Poudre Waterkeeper in Fort Collins, Colorado, and a member of Waterkeeper Alliance’s board of directors. He is also an award-winning international environmental activist, writer, and consultant who focuses on water-and river protection. He is author of the 2016 book, River Warrior: Fighting to Protect the World’s Rivers.