End of the Line for Northwest Coal Trains

By: ajcarapella

By Tyee Bridge

Waterkeepers in the Pacific Northwest win the fight against coal export.

The Cherry Point Aquatic Reserve—Xwe’chieXen in the language of the local Lummi Nation—is home to endangered herring, salmon, orca whales and long-tailed ducks. Bounded by sheer sandy cliffs and cobbled beaches, it covers about seven miles of Washington State’s north coast. And it just became bigger. In January, just days before his retirement, Peter Goldmark, Washington’s Commissioner of Public Lands, expanded the Cherry Point reserve to include 45 acres of tidelands and aquatic habitat. On the same day, he rejected a requested sublease for a loading dock on the Columbia River in Longview.

Goldmark summed up his day’s work in a press release: “These decisions are in the best long-term interest of Puget Sound, the Columbia River and the people of Washington. [The decisions] are informed by years of study and consideration, and represent the best way to protect and conserve our state’s waterways.”

But neither of these decisions sounds all that earth-shaking until you know some background. Those 45 acres at Cherry Point had been set aside for the Gateway Pacific Terminal, a coal-transfer facility projected to ship 48 million metric tons of coal per year out of the aquatic reserve. That would have made it the largest coal-export terminal on the West Coast. In turn, the Longview loading-dock had been requested for another proposed coal terminal, slated to ship out an additional 44 million tons of coal from the Powder River Basin in Wyoming.

To give some perspective: eight million metric tons of coal would pile as high as a 43-story building covering about 19 city blocks. In one day, then, Commissioner Goldmark acted to block the shipment of enough coal to bury an area the size of Manhattan six-feet deep.

Whack-a-Mole Resistance

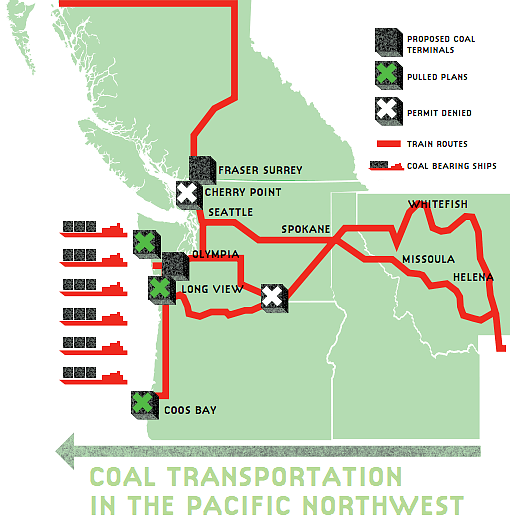

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the demise of the Cherry Point and Longview proposals was that they were the last two remaining coal-export terminal proposals out of a series of six — all put forward in rapid succession when coal demand in the U.S. plunged after 2008. For Columbia Riverkeeper Brett VandenHeuvel, Goldmark’s decision was a culminating victory in a six-year campaign to stop coal trains and terminals from invading the Pacific Northwest.

“It’s been a long time,” says Brett with a laugh. “Longview was the first proposed terminal. I have emails on that going back to July 2010.”

As coal-fired power plants were shuttered and the fracking boom brought natural gas prices down over the past decade, coal companies got into a panic to export to Asia, where demand was surging. Export coal prices climbed for almost two years after 2009, and suddenly, coal-terminal proposals were popping up like mushrooms all over the Northwest: Longview, Cherry Point, Coos Bay, Grays Harbour and others. In 2015, American natural-gas-fired plants produced as much electricity as coal for the first time in history.

“I remember early on,” recalls Brett “people were saying to us: ‘This is just whack-a-mole, what you’re doing opposing these terminals.’ They’d say, ‘Why are you bothering to fight these one at a time? We need some federal energy policy that’s going to take care of this.’ And our answer all the time was, ‘Well, number one, we don’t have a federal energy policy. And we probably aren’t going to have one any time soon that is going to protect us from coal exports.’

“Our second argument was that if we were able to knock some of these proposals off, it would buy us time. The markets change, the technology changes, to where there are more renewables available. So some of what seem like impossible fights can, maybe two, three years down the line, be won. If you’re able to hold it off, it makes room for more good things, like renewables, to become more competitive.”

And that was pretty much what happened. Pacific Rim coal prices peaked at about $142 per metric ton in 2011 then plunged to $51 per ton by early 2016. Public opposition delayed construction as the market shifted — possibly saving communities and businesses from losing even more money when the market evaporated. The economics of coal-pricing, which thrust major coal producers like Arch and Peabody into Chapter 11 filings, definitely undermined the business case for export, but well-coordinated public opposition also played a major role in keeping terminals out of Washington and Oregon.

What lessons can Waterkeepers and other community leaders take from the Northwest’s years of resistance?

The Thin Green Line

Columbia Riverkeeper was one of the organizers of the Power Past Coal (PPC) movement in the Northwest, a coalition that engaged the public regarding the dangers and drawbacks of coal exports. PPC was organized by Columbia Riverkeeper and a few other core organizations, including North Sound Baykeeper, Puget Soundkeeper, Climate Solutions, the National Wildlife Federation and Spokane Riverkeeper. The coalition served as a central support to communities opposing coal — providing facts, updates and strategy.

“We created it very early on with the idea that we would be much stronger if we coordinated our efforts,” says Brett. “Many, many groups, from the coal mines in Montana and Wyoming to the coast, worked together very closely.”

The collaboration was massive. The PPC website notes that 200 regional, community and national organizations were on board, and that “over 55 cities, counties and ports, close to 600 health professionals, 220 faith leaders, 500 local businesses (many from smaller rail-line communities), and over 160 elected officials” had raised concerns about coal exports. The Seattle-based think-tank Sightline Institute has dubbed British Columbia, Washington and Oregon “The Thin Green Line,” – a “geographic accident” that placed the traditionally progressive West Coast between North American fossil-fuel deposits (Powder River coal, Bakken shale oil, Alberta tar sands, numerous natural gas fields) and commodity markets in Asia.

Power Past Coal demonstrated that this thin line could get thick fairly quickly. When asked how the coalition grew to include such broad community support, Brett says that the first factor was “just a huge public outcry against coal export. While there was a lot of organizing, much of it happened organically. People stood up to protect what they love. Strip-mines and coal trains were a very visceral threat that people could see, and understand, and didn’t like.”

While some environmental threats are invisible, or underwater, coal trains and terminals have hard-to-hide footprints. The westbound trains haul over a hundred cars each and reach as long as a mile. And, despite dampening surfactants applied to the exposed coal, up to 500 pounds of coal-dust can be lost from each train-car in a single trip. Some communities could look forward to 18 open-car coal trains a day passing through their backyards if terminal projects were approved.

“A lot of the strongest concern was for public health. People didn’t want these trains rolling through their communities,” says Brett. “It brought out doctors, faith leaders, businesses, ranchers, farmers. We set record numbers for public hearings and public testimony.”

In the case of the Longview terminal, which was the first of the six to be proposed and the last to be refused, the Washington Department of Ecology received 257,000 public comments.

Legal challenges and engagement with regulators were the second factor that led to success, says Brett. “We had a strong and aggressive legal component to this campaign, where we challenged permits when necessary, and pushed the state and federal agencies to take a hard look at these projects. We evaluated very closely all of the permits and approvals they would need, and we designed the campaigns around those approvals. That combination of community organizing and strategic legal work was really important.”

Regional tribes and tribal organizations throughout the Northwest were also crucial in holding the line against the trains and terminals. These included the Yakama Nation, the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee, the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission and the Lummi Nation.

“They all had unique facts and unique regulatory processes,” says Brett. “The tribes played an incredibly important role in standing up for clean water, salmon and treaty rights.”

In Oregon, acknowledgment of a traditional tribal fishery was key in the Department of State Lands’ refusal in 2014 to permit a coal terminal at the Port of Morrow on the Columbia River. Similarly, the federal treaty that ensures the fishing rights of the Lummi Nation was the basis for the Army Corps of Engineers’ rejection of the $700 million coal terminal at Cherry Point. That decision paved the way for Commissioner Goldmark to return the aquatic acreage to the reserve.

“The Corps may not permit a project that abrogates treaty rights,” the commander of its Seattle District, Colonel John Buck, told a local newspaper as the Lummi celebrated the decision.

Lummi Chairman Tim Ballew added, in a written statement: “Treaty rights shape our region and nation. As tribes across the United States face pressures from development and resource extraction, we’ll continue to see tribes lead the fight to defend their treaty rights, and protect and manage their lands and waters for future generations.”

Oil Trains Ahead

Brett VandenHeuvel notes that the oil industry is much stronger than the coal industry, and is “pushing very hard” to move oil trains to West Coast export terminals. “The drilling boom in the West, trying to get that oil to the coast— it’s the same situation as coal,” he says.

One of the largest new crude-by-rail terminal proposals is the Tesoro Savage facility in Vancouver, Washington on the Columbia River. The 42-acre site would receive up to 360,000 barrels of oil per day to be loaded onto giant tankers. According to the advocacy group Friends of the Columbia Gorge, the terminal would be the largest in the country and would send four more trains down the Columbia Gorge each day, each carrying “millions of gallons of explosive Bakken crude.” For Brett and others who have spent six years fighting coal trains, it’s a case of deja vu.

“The good thing is we’ve built some pretty big, powerful lists, and local leaders and communities are much more aware of what’s going on with their ports,” VandenHeuvel says. There’s a lot more scrutiny on some of these decisions, and they’re not happening behind closed doors as easily.”

This seems to be the case. In 2016 the State of Washington received over 289,000 comments regarding the proposed crude-by-rail site.

“I think the coal export issue has actually made the oil fights—well, ‘easier’ is probably not the right word— but, you know, easier,” Brett concludes. “These kinds of proposals aren’t going away. We’re definitely still fighting them.” W

Waterkeepers Comment

Bart Mihailovich, former Spokane Riverkeeper, is now Organizer, Eastern U.S. for Waterkeeper Alliance and a veteran of the Northwest coal battle:

I hope at some point Brett and his staff at Columbia Riverkeeper write a book about some of the tactics they used. What they pulled off – and not just them, but a whole lot of people — in terms of effective strategies, with communication and group action—has just been incredible.

In 2010 the coal train issue in Spokane wasn’t on anyone’s radar. Yet it was very visible, and it affected many places all along the route — cities like Missoula, Sandpoint, Spokane, where train traffic is a fact of life. So it was relatively easy to build up non-conventional allies, like local emergency response people, who were willing to say, “We’re simply not ready for this increase in train traffic. It’s very dangerous, and lives could be lost if people are stuck behind a track waiting for an emergency response.”

Then there were allies from the passenger-rail companies and from agriculture – grain growers and apple shippers – saying, “We don’t want our tracks clogged with coal trains. This is a commodity that’s not helping anyone in the U.S.; it’s going to be shipped to China and India. We’re the local economic drivers, who are putting money and revenue back into this economy.”

So it wasn’t just this hippy green thing. It was a lot of people saying, “Let’s look at our region in a more realistic way. What kind of community do we want? Do we want train traffic shipping grain or apples or aerospace industry parts, or do we want to put everything behind coal?’”

Puget Soundkeeper Chris Wilke and his organization won a legal battle in 2016 to get coal-by-rail shipper BNSF to pay for clean-up of waterways contaminated by coal, and to study the possibility of covering their train cars. Puget Soundkeeper also achieved tightened restrictions of oil refinery effluent. Here Chris talks about the looming threat of oil trains:

In the coal case with BNSF we were arguing that every car of every train discharged coal into every waterway that it crossed. That doesn’t happen with oil trains. What we have with them is high risk and a very high consequence from any disaster. Derailments happen, and oil explodes and flames jump three stories high. It burns for days and spills into waterways, and in some cases people lose their lives.

We participated with Waterkeepers across the country in documenting aging rail infrastructure for Waterkeeper Alliance’s 2015 “Deadly Crossing” report. About 40 percent of 250 rail crossings that Waterkeepers examined showed obvious signs of disrepair and possible instability. We saw 25 crossings on Puget Sound where the footings were severely eroded. And the federal government has a limited ability to order repairs on some of these crossings because they are privately owned and railroads are the primary agency in charge of maintaining them.

Last fall the U.S. lifted a 40-year ban on export of crude oil. Right now the market is poor because of the glut of oil, but if gas goes up to $4 or $5 a gallon, you better believe they’ll be wanting to export more and more of it, and you’ll have more trains, more impact on communities, and higher risks.

Tyee Bridge is the former Fraser Riverkeeper in British Columbia. His writings have received four National Magazine Awards and seven Western Magazine Awards. He is the co-author, with Joel Solomon, of the 2017 book “The Clean Money Revolution.”