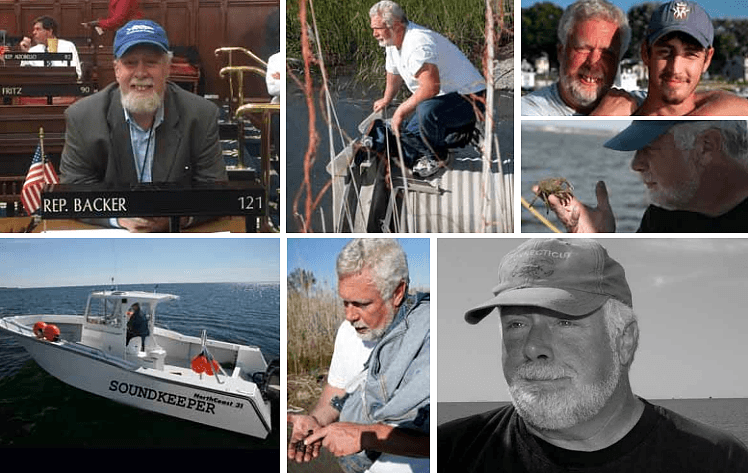

President’s Letter | Terry Backer: A Waterkeeper’s Waterkeeper

By: ajcarapella

In 1986, two burly commercial fishermen from Connecticut came to the town of Nyack, New York, on the Hudson River, to buy buck shad for their lobster pots from gillnetter Bobby Gabrielson. Chris Stabelfelt and Terry Backer were both bearded giants who reminded everyone of Bluto and Brutus from the Popeye cartoons. Terry wore an anchor earring, a ragged, faded skipper’s cap stained with seagull droppings, and a Popeye squint. I always imagined that a flock of seagulls followed him even when he got off his boat. His arms were so long and thick that it seemed he wouldn’t need a grappling hook to find his lobster pots on the bottom of Long Island Sound.

The two fishermen lamented to Gabrielson that it wasn’t possible to sue the city of Norwalk, Connecticut, which, they explained, was mismanaging its sewer-treatment plant and illegally discharging chlorine that had killed all the oyster spat in western Long Island Sound.

“We know a couple of guys who are doing just that,” Gabrielson told them.

Two days later those two guys, Hudson Riverkeeper John Cronin and I, stood on the Norwalk wharf watching sewage bubble up from submerged pipe, and 60 days later we filed suits against Norwalk, Bridgeport, Greenwich, Stanford, Branford, New Haven and West Haven. Our first settlement with Norwalk produced $180,000 in payments in lieu of penalties. We used that money to set up the Long Island Soundkeeper, and Terry Backer became its leader.

With our help Soundkeeper immediately started to sue polluters, including the famous Remington gun club at Lordship Point shooting range, which had fired 70 tons of lead into a water-bird sanctuary. We shut Remington down and took all of the sewer plants in those towns to court and forced them into compliance. Terry conducted a series of press conferences. The journalists loved him, and so did the public. I clearly remember the first time I saw one of the bumper-stickers that some fan of his had spontaneously created, touting “Backer for mayor.”

Terry noticed them too, and, even though he had never graduated high school, he decided to run for the Connecticut State Assembly – and got elected and served 23 years, becoming the conscience for the environment in Connecticut, eventually landing the job of chairman of the environmental committee, and serving as the Long Island Soundkeeper simultaneously. But, though he had joined the political establishment, Terry never lost his rebellious irreverence. He delighted in sticking it to “the Hartford stiffs.” When they told him he needed to wear a tie to enter the Assembly chamber, he explained that he’d never owned one. When they insisted, he bought a tie and wrapped it around his brow as a headband.

Terry became one of my closest allies in building the Waterkeeper movement, and one of my best friends in the world. He gave my son, Bobby, a summer job working on oyster boats in the Talmage brothers’ fleet. The experience gave Bobby discipline and immensely improved his Spanish. Terry and I had an identical vision of an army and navy of autonomous organizations running patrol boats on every waterway in the world, united through shared ideals and a centralized operation. Waterkeepers would be involved in every fight for clean water. If there were a fish-kill in Siberia, a combustible oil-train spill in Montreal, a liquefied-natural-gas plant proposal on Puget Sound, anchovy-poaching off the coast of Chile or Mexico, Terry wanted a Waterkeeper to be present.

He wanted us to lead every big battle, from the Pebble Mine in Alaska to Hann Bay in Senegal, from the Alberta tar sands to Laguna San Ignacio on the Baja California peninsula. He wanted Waterkeepers to be at every dye-house spill in Bangladesh and every illegal mine in Brazil. Wherever there was polluter with a pipe or a bully with a backhoe, a corrupt regulator or crooked politician or a greedy CEO for Monsanto, Smithfield, Duke, Exxon or the Koch brothers, Terry wanted Waterkeepers to show up with our lawyers, our boats and our detailed documentation. He shared my restlessness; neither of us could sit still for long. We had both hitchhiked and ridden freight trains across the country in our youths, and he would entertain me with stories about the commercial fisheries from Alaska to Puget Sound to Mexico where he’d worked. He had a mind that was active with intense and boundless intellectual curiosity for history, science, mechanics and astronomy.

I never got bored when I was with Terry. Coming as we did from very different places, it always struck me as extraordinary that we shared so many interests and values, chief among them integrity and loyalty. He’s headed now for a distant port but I know he’ll be waiting there for me to take his side again at the barricades.

As a young man in 1830, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. was spurred by reports of a plan to scrap the frigate known as “Old Ironsides” — the USS Constitution – to compose an ageless poem in protest. In my mind, he might’ve written it in our time about Terry Backer: It concludes:

O better that his shattered hulk

Should sink beneath the wave

His thunders shook the mighty deep,

And there should be his grave;

Nail to the mast his holy flag,

Set every threadbare sail

And give him to the God of Storms,

The lighting and the gale!