As we stood on our boards and paddled away from the cove at Malpais and turned south past the wave-break, I felt a rush of what Costa Ricans call pura vida – “pure life.” The wind was calm, the sun glaring, and the sea slightly rolling along this headland that includes the 3,000-acre Cabo Blanco National Park. Our guide, Andy Seidensticker, had moved to Costa Rica just to surf and paddleboard these waves at the southern tip of the Nicoya Peninsula on the Pacific coast.

This excursion with Carolina Chavarria, executive director of Nicoya Peninsula Waterkeeper, topped off my water-filled trip to Costa Rica this past winter. With the park to our left, we paddled just outside the wave-break, chatting, watching wildlife, soaking in the sun until we reached a warm freshwater spring that bubbled up in the ocean about 100 meters offshore. Surrounded by the bubbles, we sat on our boards and rested before paddling back to the cove. As the wind picked up and swells rose higher, the return paddling became more strenuous, as did our conversation about the watery challenges facing Costa Rica.

There are as many problems as blessings in the country’s abundant waters, and Chavarria and her staff are energetically confronting those problems, many of which are caused by the country’s booming tourist industry. Costa Rica has exemplary environmental laws but they are poorly enforced. Restaurants, hotels, and home- and road-construction generate sewage and runoff that flow directly into rivers and the ocean.

In Santa Theresa, the home of the Nicoya Peninsula Waterkeeper, five miles from Malpais, the water supply descends from the country’s inland mountains out of a massive and rapidly expanding network of dams and through a snaking tangle of canals, pipes and dikes. Many of Costa Rica’s dams also produce hydroelectric power, which provides 80 percent of Costa Rica’s electricity. Government and business officials speak of this as “clean energy” that is “carbon free.” Nothing could be further from the truth.

A few months before visiting Costa Rica I had written a post for the environmental website EcoWatch entitled “Dams Cause Climate Change: They Are Not Clean Energy.” Based on research I’d done in fighting dam proposals on my own river, the Cache le Poudre, as well as my work advocating for the already-dammed Colorado River, I’ve come to believe that hydropower is one of the biggest environmental problems our planet faces. Construction of hydroelectric dams around the world is surging dramatically, guided by the false premise that they produce clean energy, even as study after study refutes this claim.

The principal environmental menace of hydroelectric dams is caused by organic material—vegetation, sediment and soil—that flows from rivers into reservoirs and decomposes, emitting methane and carbon dioxide into the water and the air throughout the generation cycle. Studies indicate that in tropical environments and high-sediment areas, where organic material is highest, dams can release more greenhouse gas than coal-fired power plants. Philip Fearnside, a research professor at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon, in Manaus, Brazil, and one of the most cited scientists on the subject of climate change, has called these dams “methane factories.” And, according to Brazil’s National Institute of Space Research, they are “the largest single anthropogenic source of methane, being responsible for 23 percent of all methane emissions due to human activities.”

Even that number 23 may be low; the emissions can be huge even in temperate climates. A 2014 article in Climate Central offered a disturbing comparison: “Imagine nearly 6,000 dairy cows doing what cows do, belching and being flatulent for a full year. That’s how much methane was emitted from one Ohio reservoir in 2012. [Yet] reservoirs and hydropower are often thought of as climate-friendly because they don’t burn fossil fuels to produce electricity.” Another 2014 article in the same publication pointed out that, because very few dams and reservoirs are being studied, their methane emissions are mostly unaccounted for in climate-change analyses across the planet.

An article published in the 2013 book Climate Governance in the Developing World focused this failing on Costa Rica:

“These [methane] emissions, however, are neither measured nor taken into account in calculating Costa Rica’s carbon balance. Given that the nation’s electricity demand is projected to increase by 6 percent per year for the foreseeable future, and that the majority of this is to be met with increased hydroelectricity production, including such emissions in neutrality calculations would probably make it quite difficult for the country ever to achieve its goals.”

Indeed, in February and March of this year, Costa Rica’s government-owned electric utility issued press releases announcing that the country is on track to reach its “carbon neutrality” goals by 2021, stating that “88% of its electricity came from clean sources” in 2014 and that, during the first 75 days of 2015, it had been 100 percent powered by “clean” and “renewable” energy. News agencies across the world spread this misinformation about hydroelectric power. CNN claimed the prize for irresponsible reporting when it ran a TV news-segment entitled, “A Carbonless Year for Costa Rica.” More surprising still, some American environmentalists also took the bait. Green groups, including many national organizations, splashed the stories and scientifically false information across social media – 350.org ran a large Facebook meme celebrating Costa Rica’s achievement.

In the United States the Department of Energy published a report in 2014 calling for “new hydropower development across more than three million U.S. rivers and streams,” and it is not unreasonable to fear that the United Nations Conference on Climate Change later this year in Paris will be polluted with “hydropower = clean energy” propaganda.Even worse, the myth of carbon-free hydropower is embedded in the Kyoto protocol’s “Clean Development Mechanism” to address planetary climate change, and is increasingly being implemented. The program calls for a bigger investment in hydropower than in any other type of purported “clean energy.” Such recommendations heavily influence funding-decisions made by the U.S. government and international lenders such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. In fact, the World Bank states on its website: “As demand grows for clean, reliable, affordable energy, along with the urgency of expanding access to reach the unserved, hydropower has assumed critical importance.”

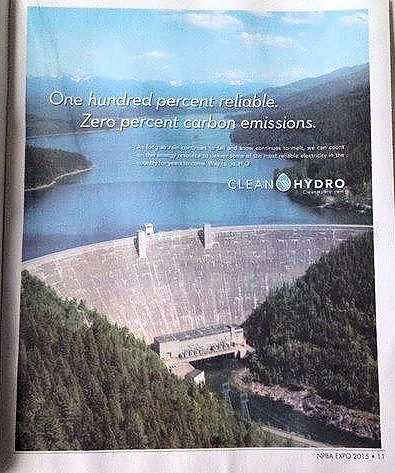

As governments and funders have gravitated more and more to hydropower over the last 10 years, the dam industry has accordingly ramped up its “green washing.” It pretends, as it has for decades, that its activities are benign, while dams and reservoirs have flooded and displaced communities, destroyed rivers and perpetrated massive human rights abuses across the planet, under the false promise of “clean and renewable energy.”

In the United States, along the Colorado River, the directors of Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams, two of the biggest river-destruction schemes in human history, continue to claim those dams supply “clean energy” and erroneously calculate the “carbon offset” of their hydropower versus the alternative of coal power. In 2013, at a public meeting of 1,200 people in Las Vegas, I heard industry officials make such claims, which have repeatedly been repudiated by Colorado Riverkeeper John Weisheit. Like the tobacco industry refusing for decades to accept that its product causes cancer, the dam industry, in public statements and advertisements, flouts the science that links methane emissions to hydropower. And to make matters worse, the U.S. Department of Energy reinforces the myth of clean hydropower.

This myth seems to permeate energy discussions everywhere. A week after my paddleboard adventure, a whitewater guide on Costa Rica’s Rio Tenorio, in the country’s northwest coastal area, described to me and a group of fellow rafters how his country’s rivers had been harnessed beneficially to produce “clean energy” and clear the way to a nearly carbon-free future.

Costa Rica is now completing the largest hydropower dam in Central America, a project that will likely devastate the Reventazón River. The 426-foot-tall structure is being touted as a shining example of Costa Rica’s commitment to the goals of the Kyoto Protocol, and the “Clean Development Mechanism,” in particular. The methane emissions it will create do not appear to have been considered, and may never be measured. But as troubling as Costa Rica’s situation may be, it represents just one small piece of an enormous global problem.

Dams are being built at a record pace all across the world. The Chinese government recently proposed to build the largest hydropower project in the world across the border in Tibet. Just one of the dams to be included would be three times the size of the current world-record-holder, Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. Further, the conservation group International Rivers reports that, “Currently, no less than 3,700 hydropower projects are under construction or in the pipeline” across the planet.

Hydropower is dirty energy, and should be regarded just like fossil fuel. And environmentalists, far from embracing it, should be battling to shut down hydropower plants and block the arrival of new ones just as vigorously as we work to close and prevent construction of dirty coal plants. At this critical moment in the planet’s history, philanthropic funders that support action against climate change must fund a movement against hydropower. Unless the scientific truth about methane emissions from dams is more widely acknowledged, pura vida will never be achieved in Costa Rica or anywhere else.