Undamming the Klamath

By: Klamath Riverkeeper

As historic dam-removal and river-restoration await congressional approval, some “dam-huggers” fight on.

By Erica Terence, Klamath Riverkeeper

Last November, in a stuffy fairgrounds building usually reserved for judging farm animals in far Northern California’s rural Siskiyou County, a few dozen commercial fishermen, farmers and Native American tribal members stood their ground in judging a very different issue. It was a hearing about one of the world’s largest river-restoration projects, involving the un-damming of the Klamath River, the West Coast’s third-largest salmon river. For nearly a century, dams have blocked fish from half the Klamath watershed, which winds for 263 miles from southern Oregon through the Cascades and Coast Ranges to California’ Pacific coast. Advocates for removing the Klamath’s four dams as well as those opposing the removal had crowded into the building to comment on a Draft Environmental Impact Statement that, dam-removal advocates argued, offered a plan beneficial both to the environment and local farming communities – a refreshing flip of the typical “fish-versus-farms” script.

Most of the dam-removal advocates had attended hundreds of meetings on the fate of the dams and the river, and had applied pressure both through the courts and grassroots organizing to call for corporate responsibility and environmental justice along the river.

In 2004, when the power company PacifiCorp applied for a new 50-year license to continue operating its four Klamath River dams, salmon advocates saw a rare opening for historic river restoration. Seizing their chance, they began a long conversation about dam-removal, based on science, the law and dollars and cents.

Also, tribal delegations traveled to Omaha, Nebraska, and to Edinburgh, Scotland, to appeal to the consciences of corporate shareholders, chief among them Warren Buffett, who owns a majority of the shares in PacifiCorp’s parent company, Berkshire Hathaway. Shortly afterward, Klamath Riverkeeper joined with tribal activists to demand that the California Water Board deny the company’s request for renewed Clean Water Act permits necessary to relicense the dams. And legal action by Klamath Riverkeeper in 2008 resulted in a ruling that forced the water board to regulate toxic-algae discharges from the dams.

Faced with protests at shareholders’ meetings, lawsuits over toxic algae, and studies suggesting that dam-removal would be at least $100 million cheaper than building federally mandated fish ladders, PacifiCorp sat down to negotiate.

The conflicting needs of the parties at the table were complex – stable, reliable supplies of water for farmers, robust and sustainable fishruns for tribal and commercial fishermen, and limited liability costs for PacifiCorp to protect ratepayers. But the collaboration that followed was unprecedented, and resulted in a pair of agreements in 2009 and 2010 that promise to remove the four aging Klamath dams by 2020, to remediate water-pollution problems caused by the dams, and to better balance water needs in the upper and lower parts of an overallocated river basin.

To implement the agreements, the U.S. Interior Department must first issue a formal finding in favor of dam-removal based on a series of studies determining whether the action is in the public interest. The studies were completed this spring as part of the process required by the National Environmental Policy Act, but the finding itself hinges on Congressional passage of the Klamath Basin Economic Restoration Act (Senate Bill 1851, House Resolution 3398), which was introduced by Congressman Mike Thompson of California and Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon. Hearings on the act will be held both in Washington, D.C. and in Klamath Falls near the headwaters of the river.

Opponents have begun maneuvering to prevent the bill’s passage, calling the dams “perfectly good” generators of clean energy and assailing the settlement’s water-sharing compromises and its cost. One landowner with reservoir-waterfront property in Siskiyou County even asked a local news reporter, if the algae behind the dams is so toxic, why haven’t we “seen a dead Indian yet?”

In the November hearing at the Siskiyou County fairgrounds, commercial salmon fisherman Dave Bitts referred to the salmon fishing closures of the past five years, which have cost his industry hundreds of millions of dollars in lost income, and responded to some of the criticism with a dose of sarcasm.

“This agreement isn’t perfect,” he said. “It doesn’t solve the problems of the Scott and Shasta or Trinity rivers (major tributaries of the Klamath). It doesn’t resolve the West Bank of the Jordan conflict either. But it would put us back to work.”

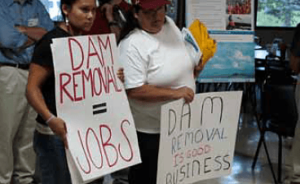

Recent federal studies have conservatively estimated that dam-removal would create about 6,000 jobs related to the demolition of the dams and a rebounding commercial fishing industry, and on that autumn day, dam-removal activists wore black tee-shirts emblazoned with the slogan “Un-dam the Klamath: Let the Jobs Flow.” It’s a message that should resonate in economically depressed Siskiyou County, but the county has remained one of the staunchest opponents of the Klamath settlement. Particularly in the center of the county, where the Tea Party flourishes, many people still cling to the status quo.

Dam-removal proponents were heavily outnumbered at the hearing by residents who fear that they will lose cheap power, tax revenues, flood-control capabilities and waterfront-property value when the dams are demolished. “Dam-huggers,” as they are called by dam-removal advocates, continue to project these fears despite the reality that the dams targeted for demolition provide no flood control or water for irrigation, and offer only a minuscule megawatt output that can easily be replaced by renewable energy sources.

The Klamath settlement, however, has earned support in most other parts of the diverse river basin, and an unlikely coalition is now hoping to thread the “Klamath Act” through Congress. But passage is not expected to be easy.

“I think we clearly have an uphill battle passing this through Congress, but it’s been an uphill battle every step of the way,” said Craig Tucker, a key Klamath campaign strategist, when the bill was introduced last November. Tucker represents the Karuk Tribe in the negotiations. Proponents of the Klamath Act, such as the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen (of which Dave Bitts is president), contend that the cost of implementing the Klamath agreements is far less than what the federal government would spend bailing out unemployed fishermen and farmers with disaster-relief dollars if the Klamath system is not fixed soon.

In contrast to the $525 million in new spending that would be authorized by the Klamath Act – $35 million annually over 15 years – farming and fishing communities lose an estimated $750 million or more in just one severely dry year.

But in a political climate where even bedrock environmental laws like the Clean Water Act and Endangered Species Act are at risk of being weakened or rolled back, nothing is certain.

For upriver and downriver communities in the Klamath Basin, the crises of the 2001 water shut-off and a vast fish-kill in 2002, caused by water diversions, are still painfully present. And 2012 threatens a possible replay of those epic tragedies.

In the Upper Klamath Basin, Klamath County commissioners have recently declared a drought, and farmers there are making contingency plans for once again diverting water to save their crops of potatoes, barley, wheat, horseradish, mint and strawberries. This is occurring while fisheries managers at the Pacific Fisheries Management Council are projecting a returning run of some 1.6 million fall Chinook salmon in the Klamath River. If those projections are borne out, commercial and tribal fishermen could enjoy the best fishing season of their lives. But if water-quality and quantity problems persist in the river, there could easily be a fish kill beyond the scale of any that the area has ever seen.

Which way the pendulum will swing this year is anybody’s guess, but it is certain that more fish will swim in the river and more jobs will be created if the parties involved work together instead of prolonging their battles well into the 21st century.