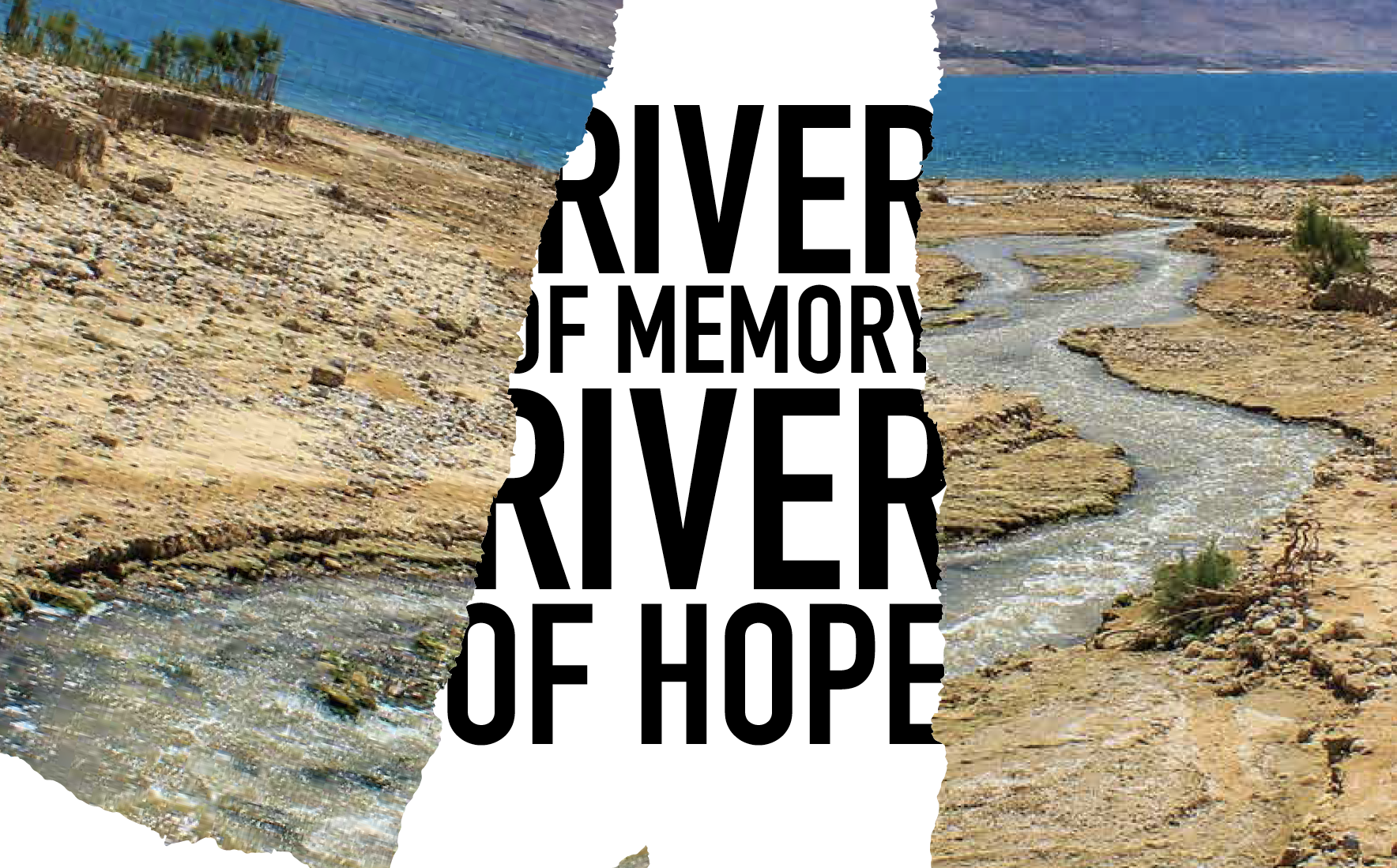

River of Memory, River of Hope

By: Ellen Simon

Ecopeace’s Israeli, Palestinian, and Jordanian Waterkeepers are proving that working together on water and climate security issues is critical to a better future for all the region’s peoples.

By Ellen Simon

The Secretary-General for the Jordanian Valley Authority sat in his dark office with its heavy curtains, wearing a dark suit, showing no emotion. The team of Jordanians and Israelis from EcoPeace had spent four years on the plan they were pitching him. They kept looking for a sign — any sign — of enthusiasm.

They gave data. He stayed quiet. They gave economic projections. No response.

For roughly forty minutes, the team kept talking. As they uncertainly gathered their briefing books to leave, he spoke.

“I remember fishing in the Jordan with my father,” he said, joy spreading over his face. “Wouldn’t it be remarkable if I could take my son fishing in the Jordan River?”

Conflict and competition have nearly drained the Jordan River, taking away 95 percent of its freshwater flows, turning a river holy to half of humanity — to Jews as the crossing to the Promised Land, to Christians as the place Jesus was baptized, to Muslims as a site where several of the prophet Mohammed’s companions were buried — into a river that trickles by, in most stretches, as an open sewer, a river you smell before you see.

It flows strongly only in a few stretches, and in the collective memory of the region’s elders.

The 50-person staff at EcoPeace, an environmental and peacebuilding organization with offices in Tel Aviv, Amman, and Ramallah, is trying to change that.

Born out of the optimism of the Oslo Accords, reshaped in its bitter aftermath, EcoPeace is the only trilateral organization in the region. It has three co-directors who also serve as the Jordan River Waterkeepers for each of their countries. Nada Majdalani, who has a master’s in environmental assessment and management from the U.K., has been the Palestinian co-director since 2017; Yana Abu Taleb, who has a degree in archeology, has been the Jordanian co-director since 2018; Gidon Bromberg, an environmental lawyer who co-founded EcoPeace, has been the Israeli co-director for 25 years.

Its board is balanced, with 12 members, four from each country. Its staff is balanced too; every staffer has a counterpart in the other two countries.

EcoPeace’s mission is to build shared water resources in a region beset by conflict. To do this, the organization enlists everyone from Palestinian students to Israeli tour guides to Japanese and German international aid agencies. In the process of working for solutions to the region’s water crisis, it’s also building an army of peacemakers — an army that may serve as a model for an increasingly parched world.

Originating at the Lebanon-Syria border, the Jordan River runs a 223-mile course, meandering southward through the Sea of Galilee and emptying into the Dead Sea. It separates Israel from Jordan and Syria, and Palestine from Jordan. A militarized border in a land of conflict, it is fenced off, laced with landmines, and largely inaccessible. Half its flows were taken by Israel, the other half by Syria and Jordan, leaving nothing for the Palestinians in the river’s southern stretch, and nothing for nature.

“While the water was taken for legitimate purposes — domestic needs, industrial needs, agricultural needs — all the water was also taken in order to deny the enemy, from all sides, additional water,” says Gidon, the Israeli co-director. “Water, in the desert, means power.”

With the water gone, all sides continued to send the river their sewage, turning it into a moving cesspool.

One of EcoPeace’s first projects brought together Jordanian, Israeli, and Palestinian researchers to study the Jordan’s flows. “Before, if you had asked what was happening at the Jordan River, the experts would say, ‘It’s the other side,’” Gidon says. “Our aim was to move away from the blame game, because blaming leads to paralysis.”

The researchers risked their lives to measure the velocity of the river and test its waters, following the hoofprints of animals to avoid landmines.

Their conclusion, released in a joint paper in 2005, was that every side had something at stake in returning the river to life, and every side had responsibility — maybe not the same amount of responsibility — for its ruin.

Another conclusion: Half the Jordan’s biodiversity, the plants and animals in the holy books of three religions, had been killed off. For instance, the Book of Isaiah in the Jewish Bible includes the phrase, “And they shall spring up among the grass, as willows by the watercourses.” EcoPeace found the willows on the banks of the Jordan were all gone. The polluted, saline water that came with conflict had killed off trees that had flourished there long before the birth of Christ.

EcoPeace found the willows on the banks of the Jordan were all gone. The polluted, saline water that came with conflict had killed off trees that had flourished there long before the birth of Christ.

EcoPeace was founded in 1994, the same year that Jordan signed a comprehensive peace treaty with Israel, and the year after the signing of the first Oslo Accord peace deal between the Palestine Liberation Organization and Israel. When Yasser Arafat, the head of the Palestine Liberation Organization, and Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli Prime Minister, shook hands on the White House lawn that September, the world watched. Peace seemed to be breaking out across the region.

At the time, Gidon was studying international environmental law at American University. His research question: Would peace be good for the environment?

It didn’t look like it. For one thing, the booming development promised by the peace deals didn’t look sustainable. There were 50,000 new hotel rooms planned on the Dead Sea alone. The wages of peace, it seemed, could suck the region dry.

Gidon’s research found there was also no infrastructure for peace, no networks of cross-border organizations to help it survive.

To build such a network, he envisioned convening the first-ever meeting of environmental leaders from Egypt, Palestine, Jordan, and Israel. He took his proposal to funder after funder. Every one of them turned him down.

Gidon’s demeanor is generally calm and reserved, but he also has plenty of chutzpah, Yiddish for audacity and nerve. He went back to them and asked again. One said, “If you can get everyone together, I’ll fund it, and I’ll come.”

The meeting was held in Taba, Egypt in 1994. The funder came. The second day of the meeting, EcoPeace was born.

Twenty-five years later, its staff is made up of people whose commitment to the work dates back to that time.

“When I was 13, 14 years old, it was still the good years after the Oslo agreement,” says Nada Majdalani, the Palestinian co-director. There was a boom of cross-border, people-to-people programs. “They wanted to prepare the young people to live together, to learn about each other,” she says. Her school was part of an environmental cross-border program, where Israeli and Palestinian teens learned together and camped together.

Nada carried memories of that experience into adulthood; those camping trips prepared her for the work she does now. Nada recruited the teacher who enrolled her in that program to EcoPeace’s staff. The teacher is now an EcoPeace program manager for transboundary environmental education.

In its early years, EcoPeace focused on creating scrupulously detailed reports aimed at decision makers, like the one it presented to the impassive Secretary-General of the Jordanian Valley Authority.

But by 2001, the region was engulfed in violence. As the promise of peace dimmed, EcoPeace’s leaders realized that, if the organization was to sway decision makers, it first had to convince ordinary people. And if it was to convince the people, it would first have to find people with enough chutzpah to meet their neighbors across the border.

EcoPeace introduced a program in 2001 called Good Water Neighbors, which pairs neighboring communities on different sides of the borders and political divides to work on common water issues. Initially, it selected 11 Israeli, Palestinian, and Jordanian communities.

Local field staff work closely in each community with groups of EcoPeace “Youth Water Trustees” and adult activists to create awareness of their own water reality, their neighboring community’s water reality, the interdependence between the two, and the need for shared solutions to shared problems.

It isn’t easy.

School children must get their parents’ permission to participate. Some parents refuse. Meeting the people whom they’ve come to regard as enemies is too much for some — it’s not uncommon for a student to walk out of an EcoPeace program in tears.

But the students who stick with it learn how to monitor the river. They work in concert at EcoPeace camp, lashing together rafts to float down the Jordan’s navigable stretches. They collect oral histories from their parents and grandparents of their memories of the river, stories about fishing, stories about jumping from apartment balconies into the deep water, stories grandparents tell with tears in their eyes about a time when the Jordan was a real river and they had access to it.

“Israeli and Palestinian and Jordanian kids coming together is a rare exception. The parents have to approve. That alone has allowed the mayors to stand up to any condemnation. Through the leadership of school kids, we’re able to create a constituency.”

“A resident of the Jordan Valley told me, ‘The best tea we used to take was when the river was clean. I’d go picnicking with my family, and we’d use the water directly from the river to make tea,’” says Yana Abu Taleb, the Jordanian co-director of EcoPeace.

The students do research projects, and present their findings to their towns’ mayors and other decision makers, asking them to lead the rehabilitation of the river.

“Israeli and Palestinian and Jordanian kids coming together is a rare exception,” Gidon says. “The parents have to approve. That alone has allowed the mayors to stand up to any condemnation. Through the leadership of school kids, we’re able to create a constituency.”

Adele Stoller, an Israeli Youth Trustee, says “EcoPeace helped me by showing me that there’s a possibility, for even a 16-year-old student such as me, to make a better change.”

The mayors’ involvement led to memorandums of understanding signed between cities on opposite sides of the conflict, and to meetings where mayors compete to see who can do more to rehabilitate the river.

EcoPeace organized an event called The Big Jump, where Palestinian, Israeli, and Jordanian mayors joined hands, in front of international news reporters, to jump into parts of the Jordan — both the clean parts and the less clean parts. The first Big Jump was in 2005; it took five years of planning. There have been five Big Jumps with mayors since then, as well as so many similar events with school children that EcoPeace no longer keeps count.

The school children have changed international policy makers’ minds, too. EcoPeace gets much of its funding from Europe; its funders include the German Christian Democratic Union’s foundation, and the Swedish International Development Agency. When Germany announced it was pulling funds for a project on the Zommer/Alexander Stream in Palestine, EcoPeace sent Youth Ambassadors to meet with German officials. The funding was reinstated.

The program has become an international model. EcoPeace trainers have taken the Good Water Neighbors program to Bosnia Herzegovina, where the program has been active since 2014; as well as Kosovo, Sri Lanka, and a watershed shared by India and Pakistan.

In the face of intransigent conflict, EcoPeace is flexible.

It trained Jordanian women to become plumbers, teaching them how to install household greywater systems. (Greywater is the name given to water that’s already been used for washing purposes, such as laundry, handwashing, showering, and bathing.) It subsidized greywater systems for impoverished Jordanian families. It bought water tanks for Palestinian and Jordanian schools so the children there had water to drink. It built paths along the Jordan, giving access to the river to people who have long been denied it. It built the Sharhabil Bin Hassneh EcoPark, which gets 20,000 visitors a year, on land from the Jordan Valley Authority.

Its work has also changed the minds of high-level policy makers. EcoPeace raised three million euros to create the first integrated regional master plan for the rehabilitation of the river and its valley. Its campaign around rehabilitating the Jordan led to Israel building a sewage plant south of Tiberius, USAID and Germany funding Jordanian sewage plants, and the Japanese government building a sewage plant in the Palestinian city of Jericho.

As sewage was removed from the Jordan’s headwaters, EcoPeace launched a public awareness campaign to let people know that, without it, the Jordan would be dry. Israel’s water authority then agreed to release 24 million gallons of water a year from the Sea of Galilee. Today, pipes are being laid that could bring hundreds of millions of gallons of desalinated water to the Sea of Galilee; EcoPeace will be advocating that some of that water be released into the Jordan River.

“Our efforts have resulted in investments of $100 million,” Gidon says. But there’s still much to be done. Jordan faces a deficit of 400 million cubic meters of water a year. The influx of Syrian refugees that began in 2011 means Jordanians only get government water one day a week, which they load into tanks in their homes.

“I try to do my laundry that same morning, before we come to work, to make sure it’s all done that same day, when we have water,” says Yana Abu Taleb, the Jordanian co-director. “Even the plants in the garden, we try to water the same day we receive that water.”

Its work has also changed the minds of high-level policy makers. EcoPeace raised three million euros to create the first integrated regional master plan for the rehabilitation of the river and its valley.

Palestine also gets far less water per person per day than the World Health Organization recommends. In Gaza, thirty percent of illnesses are from water-borne pathogens. There’s no sewer network; most homes still have waste cesspits, which allow sewage to percolate into groundwater, 97 percent of which is contaminated.

Delays in material and equipment due to more than 12 years of blockade by Israel have resulted in delayed construction of additional modern treatment plants. Power shortages frequently shut Gaza’s sewage treatment plants. In turn, the equivalent of 34 Olympic swimming pools of raw sewage is dumped into the Mediterranean daily. EcoPeace obtained records revealing that those releases intermittently shut down the Israeli desalination plant that provides 15 percent of Israel’s drinking water.

Disengagement may or may not work in politics. With water, it’s impossible.

EcoPeace has embraced that, releasing a regional plan in 2017 detailing how solar energy from Jordan could power desalination plants in Israel and Palestine. The pitch: Last century’s water conflicts were driven by a shortage of natural water, but investment and technological advances could create enough new water, through desalination, to satisfy the region’s thirst.

No one expects that to happen tomorrow. “People in the valley understand that the process is complicated,” says Yana. “They’re saying, ‘We are so pleased we are part of this process. We may not see it happen in our lifetime, but we are at least laying the right ground to see it happen for our kids and their kids.’”

EcoPeace was invited last year to speak before the United Nations Security Council, which was interested in its work because, “in the day-to-day, they hear nothing but condemnation of each other from the Palestinians and the Israelis,” Gidon says.

Nada, the Palestinian co-director, spoke first, talking about Mohammed Ahmed Salim al-Sayes, a five-year-old boy from a Palestinian family who died in 2017 of a virus he caught swimming in the sewage-choked Mediterranean.

“Rather than be negligent, Gidon and I stand before you, together, with Yana, as part of a dedicated team who refuse that our children and our environment remain hostage to the conflict,” she testified. “We are here to impress upon your excellencies that water and climate security issues are critical to a better future for all the people in our region. While politicians speak of disengagement policy, the fact is, we cannot disengage from our entire region, and our shared environment.”

“We are so pleased we are part of this process. We may not see it happen in our lifetime, but we are at least laying the right ground to see it happen for our kids and their kids.”

When both Nada and Gidon had spoken, both the Palestinian ambassador and the Israeli ambassador to the Security Council thanked EcoPeace.

“Almost every other ambassador hit the floor,” Gidon says. “They’d never seen the two ambassadors sort of agree on something.”

He added, “If we can work productively on one issue, such as water, it pulls the rug from those who claim there is no partner to peace, that we’re incapable of working with the other side because the other side doesn’t want to work together on anything.”

“We prove the opposite,” he says. “And by creating that precedent, we build trust and we build hope.”

Ellen Simon is Waterkeeper Alliance’s advocacy writer and a contributing editor at Waterkeeper Magazine.