Poison Blooms

By: ajcarapella

Florida’s waters are at a tipping point as phosphorus and nitrogen pollution and climate change combine to create a perfect storm for the increasingly frequent outbreaks of toxic blue-green algae and red tides. St. Johns Riverkeeper Lisa Rinaman and Calusa Waterkeeper John Cassani are leading the fight against this growing scourge.

By Lisa W. Foderaro

The phones at St. Johns Riverkeeper in Florida started ringing in early April of last year. Something strange was happening on Lake George, one of the St. Johns River’s many lakes, and boaters were calling to report the odd sightings. A mysterious substance in the shapes of large rectangles and trapezoids was floating on the surface.

“It looked like ice-blue plastic sheets on the river as far as you could see,” recalls Lisa Rinaman, the St. Johns Riverkeeper. “At first we thought it was some kind of pollution spill. But it was a type of blue-green algae.”

It didn’t make national headlines like the harmful algal blooms of 2018, when vast stretches of blue-green algae covered Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee River in South Florida, looking alternately like guacamole, spilled paint or an eerie Day-Glo green. But for the St. Johns River, which meanders 310 miles along the eastern part of the state, the outbreak was a harbinger of another grim season. “That particular blue-green algae was around for two weeks,” Lisa said, “but we had different kinds of toxic algae in that section of the river for 90 days.”

It didn’t make national headlines like the harmful algal blooms of 2018, when vast stretches of blue-green algae covered Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee River in South Florida, looking alternately like guacamole, spilled paint or an eerie Day-Glo green. But for the St. Johns River, which meanders 310 miles along the eastern part of the state, the outbreak was a harbinger of another grim season. “That particular blue-green algae was around for two weeks,” Lisa said, “but we had different kinds of toxic algae in that section of the river for 90 days.”

In recent years, blue-green algae and red tides have become a major focus for Florida’s 14 Waterkeepers, as nutrient pollution and climate change combine to create a perfect storm for the potentially toxic outbreaks. Runoff from agriculture, septic systems, wastewater treatment plants and nonpoint source pollution is streaming into the state’s waterways like never before, leading to a spike in nitrogen and phosphorus on which the algae feed. At the same time, global warming has led to torrential rains, which speed the movement of nutrients from land to water, as well as rising water temperatures, which can exacerbate harmful algal blooms.

Add to that the growing population of Florida (an estimated 900 people are moving to the state every day) and the sluggish response from state government, and it is small wonder that environmental stewards in the Sunshine State are feeling under siege.

At a documentary screening earlier this year, worried residents in the city of Bonita Springs peppered John Cassani, the Calusa Waterkeeper, with questions about the health impacts of harmful algal blooms. The attendees had just watched “Troubled Waters,” a film produced by John’s group. It explores the connection between toxic algae and serious diseases like liver cancer, ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease), Parkinson’s Disease, even Alzheimer’s.

“We want to make sure you know how to protect yourself,” said John, an ecologist by training. “It’s really important that you are aware of the risks. How do we fix a problem that has been decades in the making? That is really the dilemma of our time here in Florida right now. It’s not going to be easy. The underlying problem is nutrient pollution, and Florida really, really struggles with that issue.”

But Waterkeeper groups also say the growing severity of the problem in recent years – threatening public health, tourism and property values – might also mean it is finally getting the attention it is due.

Blue-green algae are not algae at all, but types of bacteria called cyanobacteria that are present mainly in freshwater bodies but can also occur in brackish water. The bacteria flourish in nutrient-heavy, warm waters and can rapidly form blooms. Those blooms can appear briefly or for long periods of time and can cover entire lakes or just small sections. When the blooms produce cyanotoxins, they can become dangerous, threatening fish, marine mammals, and humans. Exposure includes swallowing water, skin contact, and breathing in airborne droplets. Depending on the type of exposure, symptoms can include vomiting, diarrhea, rash, headache, cough, and sore throat. “And if the exposure is long enough,” Cassani says, “it may contribute to a neurodegenerative disease.” Some dogs that have drunk contaminated water have died suddenly.

Red tide occurs in salt or brackish water. Like blue-green algae, red tide has grown more severe in Florida in recent years, both in terms of its extent and its duration. Red tide harms marine life and can cause serious health problems. Exposure can cause breathing difficulties, burning eyes and rashes and can lead to seizures and other neurological symptoms in dogs.

Harmful algal blooms, or HABs for short, have popped up all over the state. But two of the hardest-hit regions are the St. Johns River and Calusa Waterkeeper’s area of responsibility, namely Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee River. Each has experienced devastating outbreaks in recent years. The blooms have hurt people and pets; killed fish, sea turtles and dolphins; closed beaches; and destroyed aquatic plants by starving them of sunlight and oxygen.

Both Waterkeeper organizations share some of the same sources of nutrient pollution, from densely populated urban areas to vast tracts of farmland dedicated to citrus and sugar production. But they face unique pressures as well.

The St. Johns River, in particular, is feeling the effects of a policy change that was aimed at protecting the Everglades. About 10 years ago, the state ordered that biosolids, or the sludge left over from the sewage treatment process, could no longer be deposited on farms in South Florida, but rather must be trucked north. Farmers there started accepting the biosolids for a fee, and not soon after phosphorus loads began fouling local waterways, including the St. Johns.

“The state legislature gave South Florida waters special protections from this practice because of off-the-chart runoff of phosphorus, so it’s really not a surprise it’s happening here now,” said Lisa, the St. Johns Riverkeeper. “It’s because you have politics driving decision-making and not science. Now the state is saying, ‘Well, we can’t ban this practice everywhere, because it has to go somewhere.’ But there is no place in Florida where this practice makes sense.”

“The damage is going to be so deep and the soil so saturated that we are going to have decades of legacy pollution problems.”

Another environmental change, albeit one rooted in good intentions, also had negative consequences for the 8,800-square-mile St. Johns watershed. To avoid wasting precious drinking water, Central Florida leads the nation in the use of reclaimed water, which is highly treated wastewater used for irrigating crops, watering lawns and golf courses, even car washes. But that water is high in nutrients, which are running off residential properties into lakes and streams. In addition, the watershed has three million septic tanks, and as Lisa points out, “even a perfectly functioning septic system can have nutrient pollution problems.”

On a cool, overcast day in late January, well before peak algae season, all that nutrient pollution was hiding beneath the surface. Instead, a tour of the middle basin of the St. Johns in the city of DeLand, aboard a flatbottom vessel called Great Blue, revealed a rich, serene ecosystem. A manatee nosed its way alongside a bed of aquatic plants. Farther along, a baby alligator rested by the shore, so well camouflaged it was visible only to the trained eye of our boat captain. An American bittern foraged for food, while an anhinga, which resembles a cormorant, dried its wings Dracula-style on a tree branch.

“The St. Johns is a gorgeous river, and most of the time it is accessible and wonderful to use in so many different ways,” Lisa said. “But it has this excess nutrient pollution problem that comes to the foreground when the conditions are right, with warmer weather, and then it can be highly toxic and make our waterways unusable.” She added that the state needed to get to the “root cause” of the problem by reducing nitrogen and phosphorus.

Advocates for clean water in Florida are encouraged that Gov. Ron DeSantis seems to be taking the threat of harmful algal blooms seriously. In the past year, he formed a Blue-Green Algae Task Force and reorganized a dormant Red Tide Task Force, two actions that Waterkeepers Florida had advocated for. In announcing the latter, his office pointed out that from the fall of 2017 to early 2019, red tides affected the state’s southwest, northwest, and east coasts simultaneously.

There are some proposed changes at the state level that could also protect the St. Johns River, including a draft regulation that would require annual soil testing of sites where biosolids are now spread. (Currently, testing is mandated only once every five years.) Moreover, farmers would not be allowed to apply biosolids on soil with an elevated water table. According to Lisa, that would affect 70 percent of the land in the St. Johns watershed where the practice now occurs.

The problem, Lisa says, is that the rule, which requires ratification by the state legislature, won’t come up for a vote until next year at the earliest, and then there is a three-year grandfather clause on top of that, delaying compliance. She and others fear that will be too late.

“By then,” she says, “the damage is going to be so deep and the soil so saturated that we are going to have decades of legacy pollution problems.”

Some 200 miles to the south of DeLand, John Cassani is dealing with a different set of problems that contributed to the historic blue-green algal blooms in the Caloosahatchee River. In 2018, Calusa Waterkeeper, based in Fort Myers, was thrust into the national spotlight when aerial images showed just how extensive the toxic blooms were; John found himself giving nearly 100 interviews to the news media in the months following the bloom, including the CBS Evening News on July 7, 2018.

A few factors set that year apart. Heavy rains from successive storms washed enormous amounts of nutrients into Lake Okeechobee, where the water level rose rapidly. To prevent flooding, the Army Corps of Engineers opened a gate to lower the water level, just as blue-green algae was spreading across its 448,000 acres. That, in turn, sent the toxic bloom into the Caloosahatchee River and its many tributaries and channels.

“We had company and we drove to Bonita Beach on the Gulf. The water was brown, and I thought, ‘Boy, I’m having trouble breathing.’ When I walked back to the car, I felt better.”

“Essentially the Corps, without intending to, inundated the river and eventually the estuary with probably the worst blue-green algae bloom in recorded history in this area,” John told the audience after the screening of “Troubled Waters.”

In the audience was Lucille Hartman, who lives in Pelican Landing, a sprawling residential community in Bonita Springs that hosted the event. She recalled her own encounter with red tide last summer. “We had company and we drove to Bonita Beach on the Gulf,” she said. “The water was brown, and I thought, ‘Boy, I’m having trouble breathing.’ When I walked back to the car, I felt better.”

The experience made her aware of the dangers of agricultural and lawn fertilizers. “We are all going to have to get used to those pretty little dandelions if we want to save the natural resources that we have,” she said.

Calusa Waterkeeper, Waterkeeper Alliance, and the Center for Biological Diversity ended up filing a federal lawsuit in the southern district of Florida. The suit challenged the Army Corps on its releases from Lake Okeechobee, asserting that the agency ignored the potential health impacts on people and wildlife. (Also named were the U.S. Department of the Interior, the National Marine Fisheries Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.) While that litigation unfolds, the Corps says it is working to update its current discharge schedule, and some environmental advocates believe the Corps may have already begun modifying its approach by proposing a “Deviation” to the current Lake schedule to better protect downstream communities from toxic algae.

“The Army Corps miraculously found some latitude to alter their release schedule,” said K.C. Schulberg, executive director of Calusa Waterkeeper, pointing to the lake-water discharges last year. (K.C. wrote and directed “Troubled Waters.”)

“Historically,” he added, “they said they were just following the rules, that they had to release when the water got to a certain point. The change is partly because of the public outcry, and our lawsuit probably had some effect as well.”

While there is optimism on that front, at least in southwest Florida, Waterkeeper groups and other advocates across the state are bitterly disappointed by bills that recently passed in the Florida Senate and House of Representatives. Called the Clean Waterways Act, the legislation is so weak, advocates say, that it might as well have been written by polluters and corporate interests. Rather than take aim at agricultural runoff and the spreading of biosolids, the legislation tweaks regulations for wastewater treatment plants and septic tanks.

In a newspaper opinion piece, John Cassani wrote that the proposed law relies on the flimsy principles underscoring the adage: “The solution to pollution is dilution.” He chastised lawmakers for “deceptive criteria” and “blurred or meaningless compliance thresholds for clean-up plans.”

In a statement, St. Johns Riverkeeper Lisa Rinaman pointed out that SB 712, as the Senate version of the bill is known, “weakens efforts to protect our waters by providing polluter loopholes that allow the dangerous dumping of concentrated human waste to further degrade our springs, our rivers and our waters.”

Calusa Waterkeeper, along with the Center for Biological Diversity and the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation, also asked the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to adopt new water-quality standards and swim advisories for two cyanotoxins.

“Our petition came on the heels of the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s announcement in May 2019 of their final guidelines for recreational exposure to both cyanotoxins,” John Cassani said. “The states are under pressure to adopt the standards, and if they don’t, they have to explain to EPA why they are not.”

Over lunch at St. John’s River Grille in DeLand, Lisa explained the political dynamic in the state of Florida, one that puts certain waterways like the St. Johns River at a disadvantage. South Florida, she said, has more political clout than North Florida. Even though the current governor is more sympathetic than the previous administration, he still seems to be “sending all his environmental promises” to South Florida.

“What’s irritating is that they thought moving [biosolids] from one location to another was a solution,” she said. “They also thought no one was paying attention. I don’t think they realized it would cause so much damage so quickly.”

A growing concern among scientists and residents in Florida is the possible connection between the toxins produced by blue-green algae and neurodegenerative diseases like ALS, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s. One class of toxins, known as microcystins, has long been known to cause damage to the liver. But another toxin produced by blue-green algae is an amino acid known as BMAA, or beta-methylamino-L-alanine. The neurotoxin, which accumulates in the marine food chain, has been found in the brains of people who have died from those diseases.

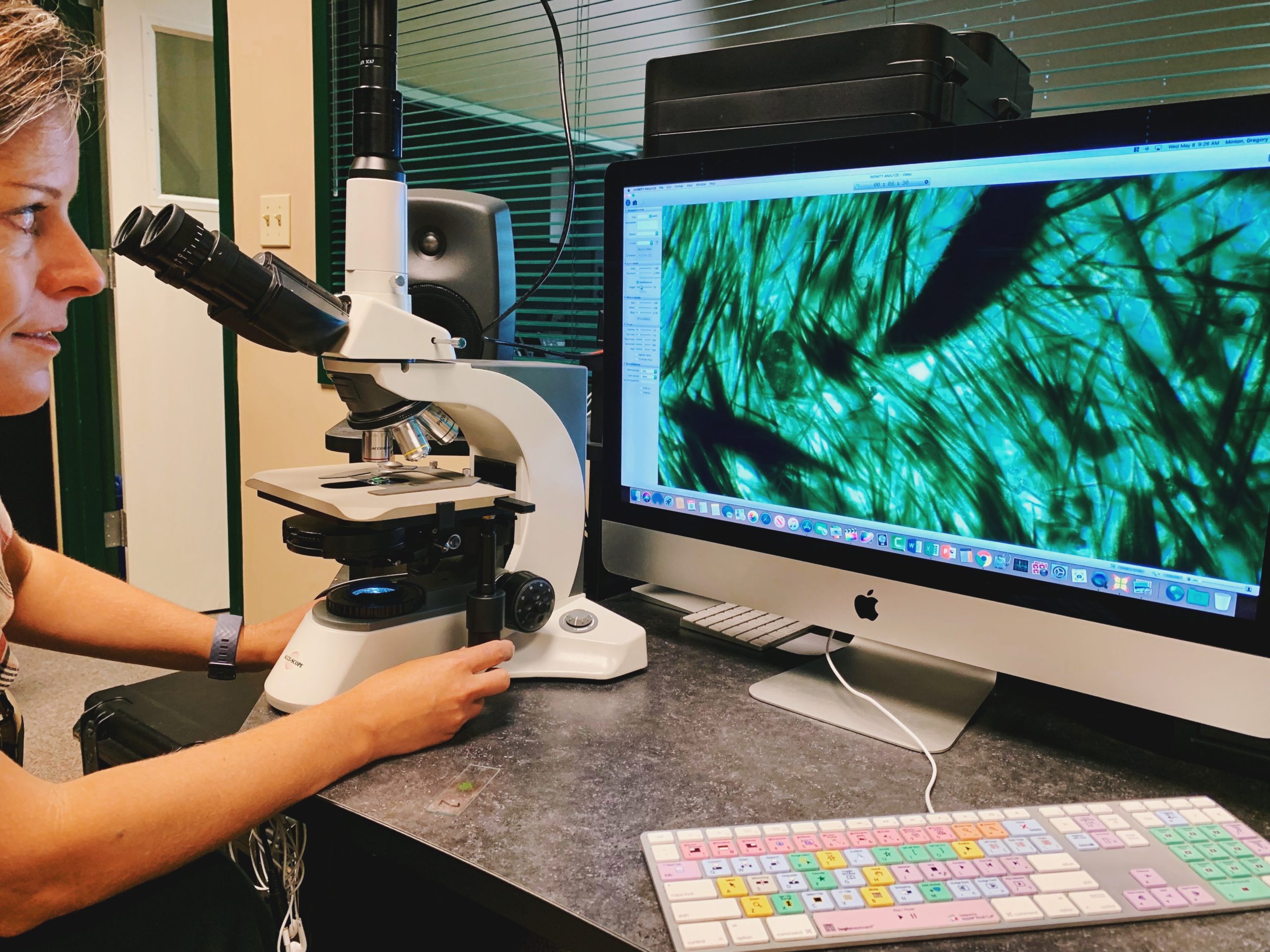

A study published last year in the journal Plos One examined the brain tissue of 14 dolphins from Florida and Massachusetts. The dolphins died after becoming stranded in areas that are subject to harmful algal blooms. All but one had BMAA in their brains. “Exposures to cyanotoxins are a public health concern as they are linked to organ system damage and disease,” the study concluded. “Examining the levels of the cyanobacterial toxin BMAA in apex predators, such as dolphins and sharks, provides a powerful bioindicator of the potential for human exposures.”

One of the authors of the study was Larry E. Brand, a professor of marine biology and fisheries at the University of Miami. He worries that health officials are deeming water bodies safe after ruling out the presence of microcystins only. “No, it’s not OK,” he said in an interview, “because you don’t know about all these other toxins.”

While some scientists have thrown cold water on the link between cyanobacteria and brain disease, Brand believes there is an association, and possibly a cause-and-effect. He has found high concentrations of BMAA throughout the marine food web in South Florida, including shrimp, crabs and fish. In a separate study, he examined the brains of six dolphins in the Indian River Lagoon, and “five of the six had high levels of BMAA in their brain, comparable to that which you see in the brains of humans that have died of Alzheimer’s or ALS.”

Researchers who study the behavior of dolphins in the lagoon also report that they are acting strangely. “They tell me that they see dolphins that seem confused, that seem to be getting lost, swimming up rivers into freshwater lakes,” Brand said. “So it’s almost like an Alzheimer’s patient. This does seem like a very serious health risk to people here in South Florida. I would not eat any of the seafood in any of these water bodies that get blooms of blue-green algae.”

One of the worst outbreaks of red tide in years occurred along the Gulf Coast, centered on Sarasota Bay. “There was vast devastation of marine life,” said Justin Bloom, founder of Suncoast Waterkeeper. “Our waterways were clogged with dead fish. The ones that tug at the heartstrings were whales, porpoises, sea turtles, snook and tarpon. I mean these are the keystone species that people cherish here.”

“What’s irritating is that they thought moving [biosolids] from one location to another was a solution. They also thought no one was paying attention.”

The suspected sources of the extreme red tide, which lasted from late 2017 to early 2019, included agricultural and stormwater runoff. But aging sewer systems were also to blame. In a 2018 article on the bloom’s toll on birds and marine life, Brand told The New York Times that red tides were now 15 times worse than 50 years ago. Suncoast Waterkeeper, which protects the Sarasota Bay and Tampa Bay estuaries, was a plaintiff in an action against Sarasota County under the Clean Water Act; the group had sued the cities of Gulfport and St. Petersburg over sewage discharges even before the outbreak.

All three settled, collectively committing hundreds of millions of dollars to upgrade and repair collection pipes and treatment plants. “It was incredibly successful and we are super proud,” Justin says. “Now we have our sights on the next city polluting Tampa Bay with its big nitrogen problem.”

Because there are so many residential communities in Florida, some environmental advocates believe enlisting their muscle in the fight for safer, cleaner waters is key. While some communities are reluctant to engage in politics, Pelican Landing in Bonita Springs, with 3,318 units of housing and three golf courses, has entered the fray. The association’s Eco Club, for instance, organized the screening of “Troubled Waters.”

“We want to be as green as possible and cut down on fertilizers,” said June Ricks, president of the Pelican Landing Community Association, which has passed resolutions in support of state legislation. “It’s alarming, especially the connection to Parkinson’s and other neurological diseases. We all need to take action.”

Lisa W. Foderaro was a staff reporter for The New York Times for more than 30 years and has also written for National Geographic, Audubon Magazine, and Adirondack Life.

Fourteen Waterkeepers, One Voice

To confront the ever-growing list of problems facing Florida’s waters, the state’s 14 Waterkeeper organizations banded together in late 2018 to form Waterkeepers Florida. The idea was to share expertise and speak with one voice on issues ranging from algal blooms to plastic pollution to land conservation, so that it was more likely that the state’s lawmakers and others would take notice. St. Johns Riverkeeper Lisa Rinaman was named the chair, and Matanzas Riverkeeper Jen Lomberk the vice-chair.

The umbrella group advocates for 45,000 square miles of watershed, which is home to 15 million residents. “It seemed like it would benefit all of us if there was a little more cohesion and communication across all the Waterkeeper groups in the state,” explains Jen. “In Florida, everything is so connected when it comes to waterways, and we all sort of had tunnel vision with our own watersheds.”

A main focus this year was the Clean Waterways Act, a package of state legislation that Waterkeepers fought to strengthen, but without success. The act failed to address the problem of agricultural runoff and biosolids, they say, and only nibbled around the edges of septic-tank and stormwater pollution by initiating a process for new state regulations.

“We weren’t able to get it amended to our satisfaction,” says Jen. “But we were able to change the narrative about the bill in the media from ‘this is the answer to the state’s water quality issues’ to ‘it’s a start but there’s a lot more work to be done.’” Given Florida’s current political climate, Lisa sees that as a victory. “Getting legislators and state agencies to admit that this was not the ‘silver bullet’ they originally branded it as, was an important reframing of the issue.”

Another recent lobbying effort centered on Florida Forever, the state’s land acquisition program. Since the inception of the program in July 2001, the state has purchased some 814,000 acres of land with more than $3 billion. But Waterkeepers Florida says the current funding thresholds are inadequate.

“We are losing natural lands to development at an alarming rate,” Jen says, “and so we are losing the ecosystem services that those lands provide, including stormwater retention, water filtration, and wildlife habitat.” Historically, Florida Forever was funded at around $300 million. Last year, that amount fell to $33 million, and this year, advocates expect the state to allot $100 million, rather than the $470 million Waterkeepers called for. “Getting it back up to $100 million after years of negligible funding was still progress,” says Jen.

Currently Waterkeepers Florida is pushing the state to adopt water quality standards for cyanotoxins as well as urging the state department of health to uniformly implement public health notifications and warnings when harmful alga blooms are present.

The group is also fighting a new regulation from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that will drastically weaken the Clean Water Act, harming public health and Florida’s already fragile ecosystems. The regulation has been branded by the Trump administration as the “Navigable Waters Protection Rule,” but it definitely won’t protect America’s waters. Instead, it’s a gift to polluters and a grave environmental threat. The rule narrows the definition of “waters of the United States,” which are the waters the Clean Water Act authorizes the federal government to protect.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection estimates that more than 800,000 acres of wetlands in the Panhandle region would lose protection under the proposed changes to the rule. In addition to this, almost half of Florida’s 52,000 miles of rivers and streams could lose the protection. “Any risk posed to these waterways is a direct risk to our economy and our livelihoods,” states Waterkeepers Florida’s annual report.