One More Reason to Fight Alaska’s Pebble Mine

By: Bart Mihailovich

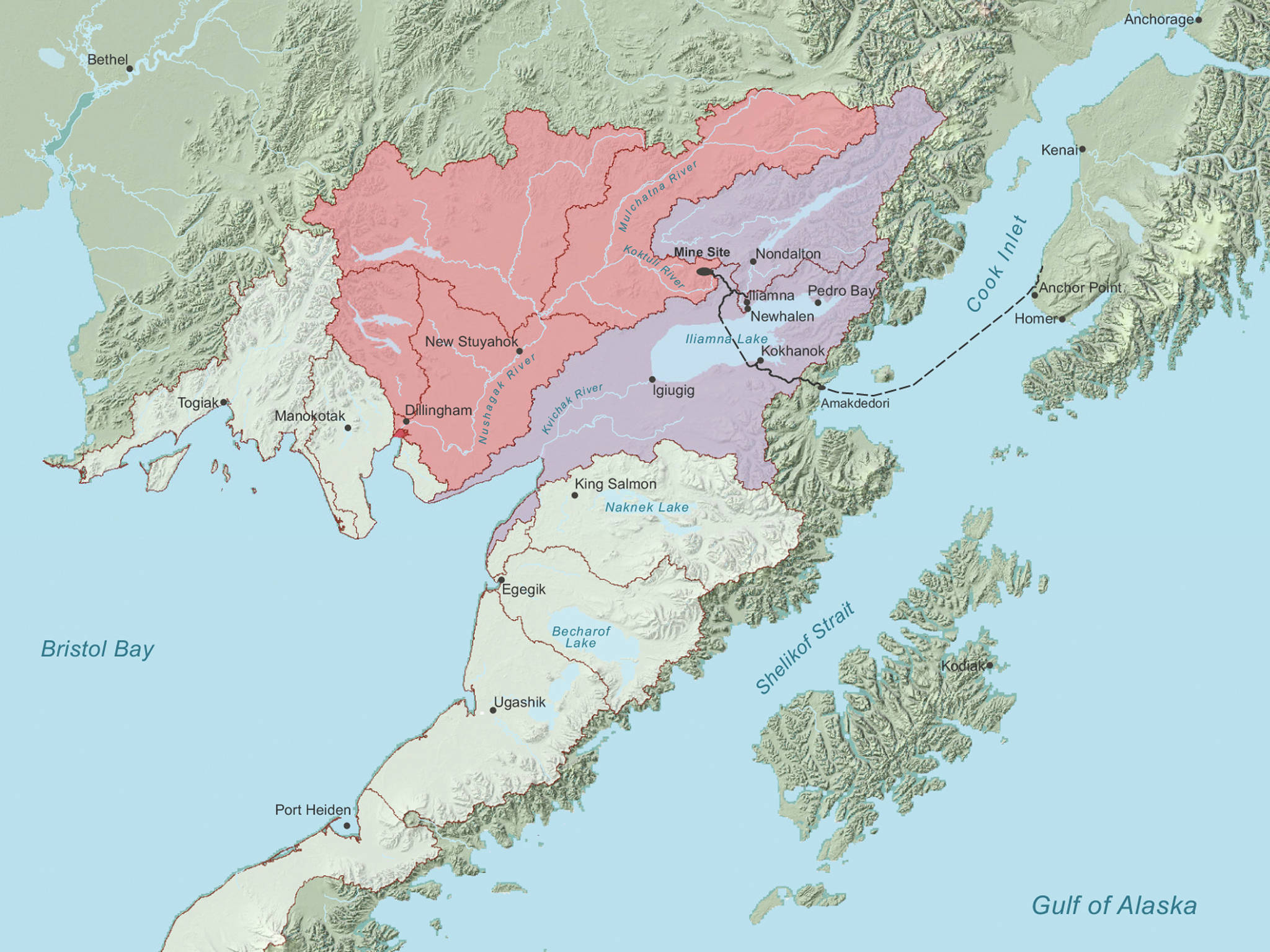

Bristol Bay is home to the world’s largest salmon fishery, supporting all five species of Pacific salmon and producing about 46 percent of the world’s sockeye salmon harvest. It also provides habitat for 29 fish species, over 190 bird species, and over 40 terrestrial animals that rely on Bristol Bay’s well-being for their survival.

All of this is being threatened by the proposed Pebble Mine project at the headwaters of the Nushagak and Kvichak rivers in Bristol Bay. If built, the Pebble Mine would be one of the world’s largest open-pit copper and gold mines, with an earthen dam that would ultimately hold up to 10 billion tons of toxic tailings and contaminated water, threatening nearby waterways with heavy metals and other toxic pollutants.

If it feels like you’ve been hearing about the Pebble Mine fight for a long time, it’s because you have. Cook Inletkeeper was the first green group to meet with Northern Dynasty — the Canadian mining company behind the Pebble project — way back in 2003. Since that time, four major investors have come and gone, yet, like a zombie, the project keeps returning to life. Now, the Trump Administration has helped revive the project — and with a state government in the pocket of the mining industry — Pebble’s pushing hard to get the federal permits it needs to start construction.

While most of the attention around the Pebble Mine has focused on Bristol Bay and its incredible salmon fisheries, few people know the project will also devastate the highest concentration of brown bears on the planet. That’s because Pebble’s natural gas pipeline — to power the mine — and its export terminal would tear open the wildlands of Lower Cook Inlet. Pebble would build this infrastructure at Amakdedori Creek in Kamishak Bay, in close proximity to two national parks (Katmai and Lake Clark) and the McNeil State Game Refuge.

In 2018, staff from Cook Inletkeeper took the trip 80 miles across Cook Inlet to check out the area around Amakdedori Creek first-hand. In addition to the spectacular scenery and incredible wildlife, Inletkeeper confirmed what it had heard from numerous fishermen: the area’s radical weather patterns, coupled with shallow reefs and massive (25’) tides, make it no place to load large bulk carriers with ore concentrate.

“The Pebble people are desperate to find investors, so they cobbled together a ridiculous export scheme to make the project seem viable,” said Inletkeeper Bob Shavelson. “But Alaskans who live and work on the water know Pebble’s just blowing smoke.”

In the race to get its federal permits, however, Pebble is cutting a lot of corners. For example, in its environmental reviews, it completely ignored the significant economic contributions that come from a growing bear-viewing industry. In response, Inletkeeper commissioned a study that found the bear-viewing industry drives around $40 million into Alaska’s economy each year.

That’s a lot of money. And it helps explain why bear guides, bed and breakfasts, and a host of small businesses have come out to oppose Pebble and its plans for Lower C ook Inlet.

“Alaskans overwhelmingly oppose the Pebble Mine,” says Shavelson. “But the Trump Administration doesn’t care, and it’s ignoring science and the law by trying to ram this stupid project through.”

The Army Corps expects to issue a final EIS this summer, and Inletkeeper will join others in litigation to stop it. “Because from every angle,” Shavelson adds, “the vantage point is the same: we must say No Pebble Mine.”