Sunny Skies, Troubled Waters

By: ajcarapella

Waterkeepers contend with the human impact on Florida’s aquatic systems.

Photos and text by Lynne Buchanan

Florida’s waterways are treasures that are being irreparably damaged by the impacts of climate-change, agricultural pollution, increasing population, urban growth and land development. As population expands, estuaries and waterways are being depleted by diversion of water from aquifers. More lawns, roadways and water-drainage pipes degrade water-quality. At the same time, sea-level rise and increasingly severe storms threaten the quality of freshwater rivers, lakes, coastline, riparian landscapes and native species.

Lynne Buchanan has spent the past three years working in Florida with Waterkeepers, springs experts, environmental scientists and indigenous people to document what is happening and raise a call to action to preserve these resources that are essential to our survival and cherished for their natural beauty. This photo essay features seven of the Waterkeepers she has worked with and highlights the most important issues in each of their watersheds

Lynne Buchanan is a fine art and environmental photographer. She is currently working on a book about water issues in Florida, to be published soon.

John Paul

President of Caloosahatchee Citizens River Association, a Waterkeeper Alliance Affiliate

The Caloosahatchee River in southwest Florida receives overflows of agricultural runoff from Lake Okeechobee, and during the past year algae associated with these discharges extended into the Gulf of Mexico as far as Sanibel Island to the north and into Naples Bay and all the way to the Keys in the south. The river also suffers from runoff caused by overdevelopment, orange-groves, cattle-grazing and other farming operations. South Florida’s orange crop has declined up to 70 percent due to citrus greening disease, which John Paul, president of Caloosahatchee Citizens River Association (CCRA), a Waterkeeper Alliance affiliate, believes is associated with drought, climate-change and overuse caused by development in the area. The water table all over Florida is dropping, which is making trees more susceptible to bacteria and other stressors. In an attempt to reduce runoff and improve the health of his groves, Paul introduced underground irrigation, which directly targets roots and allows him to control exactly how much water enters the soil – as opposed to surface-watering, whereby ditches collect excess amounts of fertilizers and other nutrients. Underground irrigation has made it possible for him to reduce water-consumption by 40 percent and eliminate drainage ditches. Trees also have become healthier, which reduces his need for pesticides.

CCRA monitors water quality throughout the region and studies the effects of domestic, commercial and agricultural uses. They work to increase public awareness of issues facing the river, so that impacts on riparian and estuarine systems, wildlife habitat and marine life can be mitigated.

Justin Bloom

Suncoast Waterkeeper

Environmental attorney Justin Bloom heads Suncoast Waterkeeper, which oversees Sarasota, lower Tampa and Terra Ceia Bays and Manatee River in westcentral Florida, all of which have been adversely affected by phosphates. Working with him to protect these waterways are Charles Kovach, Suncoast Waterkeeper, chief scientist and advisor to several other environmental organizations, and Andy Mele, former executive director of a major Hudson River environmental group.

An important issue for the Waterkeeper arose in September when a 45-footwide sinkhole under a gypsum stack at the Mosaic phosphate plant in Mulberry caused water containing low-level radiation and other pollutants to pour into the aquifer, potentially poisoning the drinking-water in the area. Phosphates also make their way into the bays and river through runoff, frequently causing algae blooms in areas where the water is more stagnant.

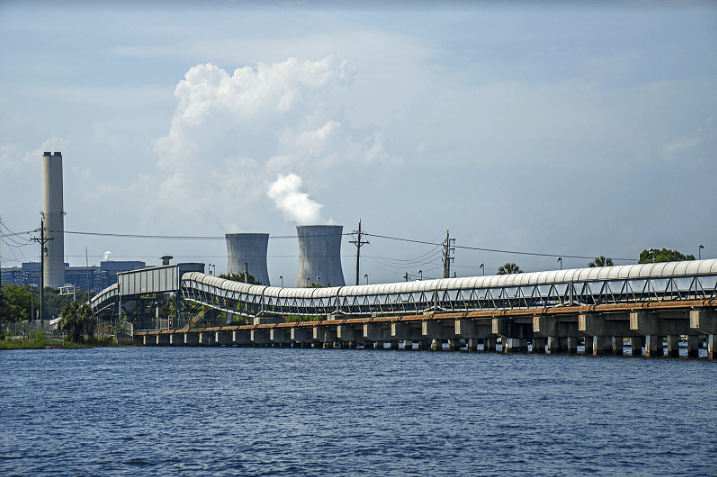

Suncoast Waterkeeper is involved in litigation regarding violations of the Clean Water Act from stormwater and sewage pollution, which has been particularly acute in the city of St. Petersburg. The Waterkeeper and several other environmental groups have also filed lawsuits regarding coal-ash pollution and its impact on endangered species. Coal-ash pits at Tampa Electric’s Big Bend Power Station cause arsenic, lead and other toxic substances to leach into the watershed.

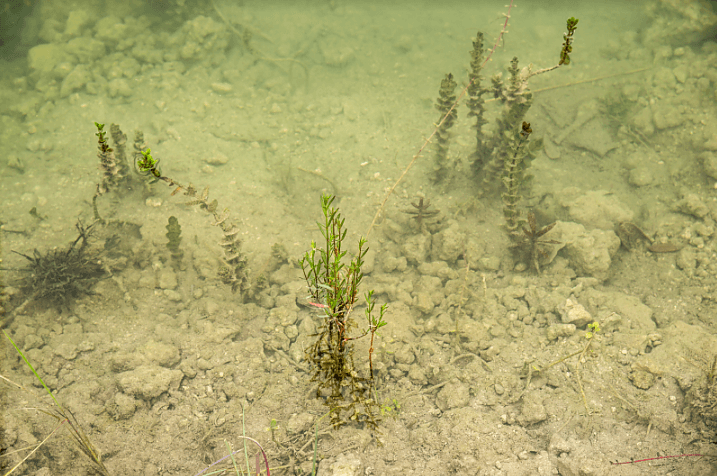

Another area of concern is the effect of residential and commercial development and the need to hold developers to the highest standards of environmental protection, particularly in regard to mangroves and sea-grasses. Sea-level rise and loss of sand are another constant threat to the area, and Suncoast Waterkeeper is calling for a comprehensive review to identify sources for sand-replacement and alternative strategies for shoreline protection.

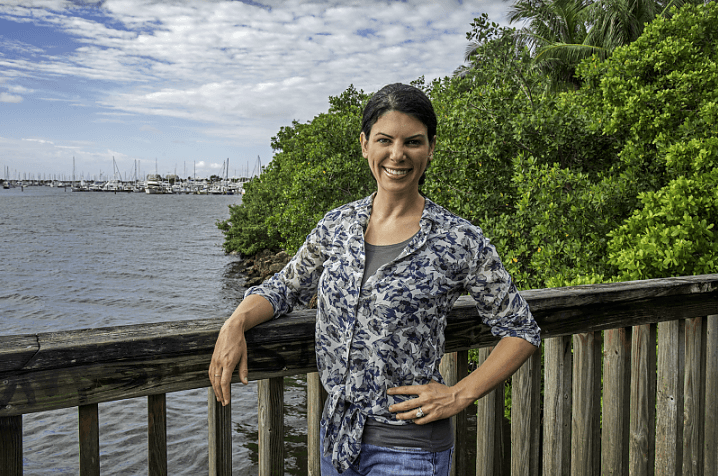

Lisa Rinaman

St. Johns Riverkeeper

The 310-mile St. Johns River in east-central Florida is the longest in the state, and 3.6 million people live in its watershed. The drainage basin is 8,840 square miles, and its estuary is 2,777 square miles, which is also the largest in Florida. There are 85 springs on the river, which account for approximately 30 percent of its water. According to St. Johns Riverkeeper Lisa Rinaman, the biggest threat facing her river is excess water-usage. Agriculture and other industries are continually increasing the amount of water they draw from the river. And as sea level rises (the St. Johns flows into the Atlantic Ocean), the percentage of saltwater in the river increases and wetlands are lost. Estuaries are also harmed when the mix of saltwater and freshwater becomes too salty.

St. Johns Riverkeeper is involved in frequent litigation to protect the springs and the fresh water they produce, and it is opposing toxic discharges from the St. Johns River Power Park in Jacksonville and the Seminole Electric Plant upstream. Another problem it is taking on is dredging to accommodate big ships that use the port in Jacksonville, an activity that erodes the riverbanks and causes docks to crumble. The St. Johns and its tributaries are also confronting pollution from heavy metals, including mercury, and the presence of excess nutrients and algae blooms, some of which are toxic. Lots of human and animal waste also empties into the river from the most heavily populated areas it flows through.

As a result of the efforts of Rinaman and her organization, the river is no longer listed among the ten most endangered in North America. But it still faces many challenges. St. Johns Riverkeeper is committed to monitoring, addressing and resolving the following issues: nutrients, bacteria, water-withdrawals, sedimentation, loss and degradation of habitats, pollutants, public access, proposed dredging, wetland impacts and loss of riparian zones.

Laurie Murphy

Emerald Coastkeeper

The Florida Panhandle could not be in better hands than those of Laurie Murphy (right), who holds a B.S. in Oceanography and a master’s certification in geographical information science. Murphy oversees all four watersheds in the Panhandle, including Pensacola Bay, and she confronts a wide range of common issues throughout these watersheds: septic-system failure, erosion and sedimentation, nutrient-loading from fertilizers, red tide, and leaching of heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). And then there are the problems of animal-waste, industrial-paint-plant discharge, oil-spills, commercial-vessel pollution, residential development, and household garbage. One of the biggest issues she is dealing with is the Gulf Power Company’s Crist Plant at Pensacola, where coal ash from unlined pits is migrating into the water. Another major problem is an outdated water-treatment plant in Pensacola Beach that is pumping toxins into Pensacola Bay. There are also seven super fund sites in her area, including an old creosote plant and the Pensacola Navy Compound. Residues of jet-fuel and chemicals, including arsenic, mercury and other heavy metals are still present in the water from these sites, and Murphy is working with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to monitor toxicity.

Another concern is dredging, which replaces sand lost from sealevel rise. In addition, many tar-balls remain buried in the Gulf sand from the BP oil-spill, and a hurricane could bring these back to the surface. And she is also in the midst of legal battles to improve water quality throughout her area – which have her considering enrolling in law school to acquire even more tools in her fight for her waterways.

Rachel Silverstein

Miami Waterkeeper

Rachel Silverstein became executive director of Miami Waterkeeper in June 2014, two years after earning a Ph.D. from the Department of Marine Biology and Fisheries at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School for Marine and Atmospheric Science.

One of the most serious issues she has been contending with is massive dredging for the expansion of PortMiami. After mediation sessions led to a settlement agreement, Miami Waterkeeper was able to secure improved protections for marine life by expanding the scope of coral-relocation projects, expanding monitoring requirements, limiting blasting during spawning- and feeding-times for protected species, and obtaining $1.31 million for the Biscayne Bay Trust Fund, which will fund much-needed bay-restoration and enhancement projects. Another constant concern is sea-level rise, which has already caused the flooding of sewage-treatment plants and saltwater intrusion into inland wells. Stormwater-drains have become ineffective and frequently back up during full moons, heavy rains and storms. Costly pumps have been installed throughout the area to return water to the bay, but untreated runoff is causing further degradation to the bay.

Silverstein is also focused on the Turkey Point Nuclear Power Plant, which was literally carved out of the Biscayne Bay shoreline. The site includes a network of exposed, unlined cooling-canals that are creating a saline plume that is spreading out into the bay and heading toward the Florida Keys. Now construction of two more power plants is being planned, unrealistically allowing for only one foot of sea-level rise in the next 50 years.

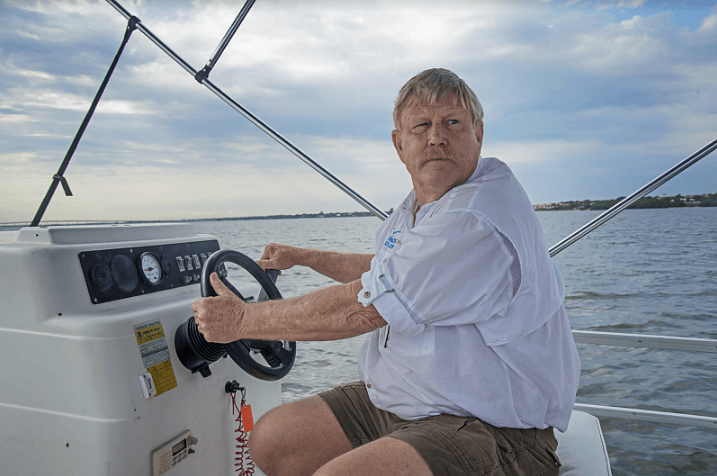

Marty Baum

Indian Riverkeeper

Marty Baum, the Indian Riverkeeper, faces daily one of the greatest challenges in Florida’s waterways – polluted nutrient discharges from Lake Okeechobee. Last summer these caused unprecedented cyanobacteria blooms that made national headlines. Baum was able to follow a 23-mile cyanobacteria bloom on canal C-44, which links Lake Okeechobee with the St. Lucie River, which empties into the Indian River Lagoon. Not only is it unsafe to touch water containing cyanobacteria; it is also health-threatening to breathe near it.

The Indian River Lagoon was once one of the most biodiverse of all bodies of water in North America. Now, the infusion of nitrogen and phosphorous from Big Agriculture entering the lagoon in tainted stormwater and agricultural runoff as well as discharges is drastically reducing its number of life-forms. Cyanobacteria, brown algae blooms, and high levels of other bacteria have led to the destruction of sea-grass beds as well as extensive fish kills. The poor water quality of the Indian River Lagoon is causing health issues for marine life throughout the watershed, including manatees and pelicans. Discharges from the Jensen Beach Power Plant are also implicated in the loss of sea-grass and the disruption of the manatees’ migration pattern.

As a fifth-generation Floridian who remembers the lagoon when it was pristine and thriving with life, Marty Baum is both saddened and angered by its current condition, but also committed to leading the fight to see it restored.

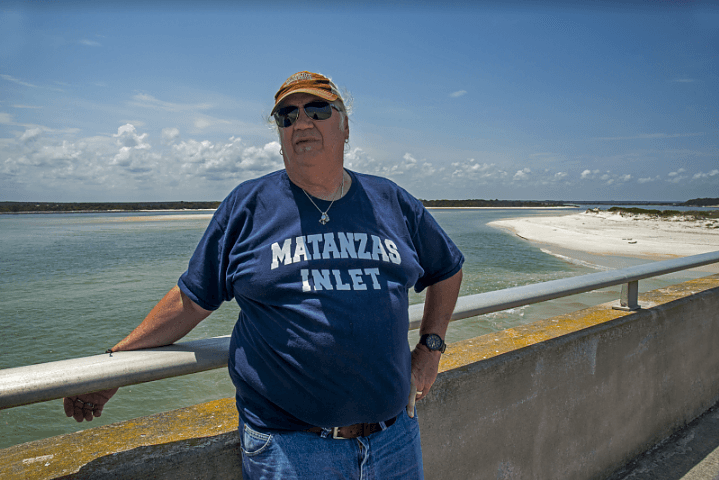

Neil Armingeon

Matanzas Riverkeeper

Neil Armingeon, formerly the St. Johns Riverkeeper, became the Matanzas Riverkeeper in 2013. So his combined experience has familiarized him with virtually all the issues facing Florida’s waterways. The Matanzas, which flows south from St. Augustine in the northeast, is a unique river system in the state. Only 23 miles long, with a watershed of 980 square miles in just two counties, an area in which there is no industry and only one urbanized locality, the Matanzas has been called the “Last Best River in Florida.” The biggest issue Armingeon is contending with is sea-level rise, as was evident in the massive flooding caused by Hurricane Matthew, which extensively damaged the Matanzas Riverkeeper headquarters. The City of St. Augustine has already elevated parts of its seawall about two feet, but flooding still occurs, even during minor storms. As a result, the intrusion of saltwater into the area’s freshwater wells has increased markedly.

Armingeon’s attention is also focused on development that could negatively affect the river, which, along with Pellicer Creek, has been designated an “outstanding water and aquatic reserve.” In September 2015, Matanzas Riverkeeper was able to defeat a proposal to build 999 homes on 772 acres, which would have had significant negative effects on these irreplaceable waterways.

Other problems that Armingeon is dealing with include wastewatertreatment plants, both existing ones and others associated with new development, and seismic testing for oil under the Atlantic Ocean, which was at first approved by the Obama administration but, because of widespread opposition, later withdrawn.