Last hope for America’s “Most Endangered River”

By: ajcarapella

Apalachicola Riverkeeper Dan Tonsmeire is fighting for the life of his river, but it’s the U.S Supreme Court and the Army Corps of Engineers who will decide its fate.

By Lisa Garcia

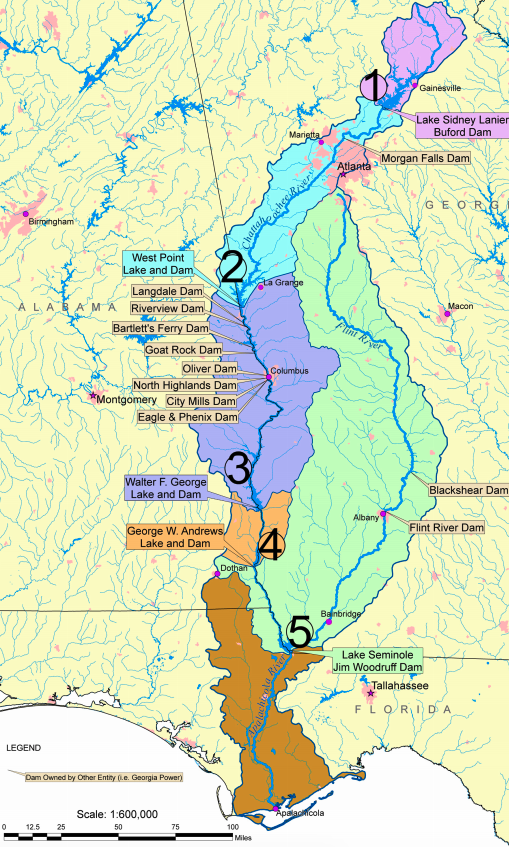

Extreme drought, unprecedented low waterflows, unrestrained and unsustainable growth, endangered wildlife and a collapsing estuary. Anyone dealing with these threats would most likely feel that he or she was caught in a nightmare. Add irresponsible government regulators and a last-hope U.S. Supreme Court case, and the horror deepens. But this isn’t just a bad dream for Apalachicola Riverkeeper Dan Tonsmeire and many of the residents around the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River Basin. It’s a 27-yearlong reality that reached a critical juncture in 2016 when the river-system was designated “America’s Most Endangered River.”

There is one last chance to turn things around. The U.S. Supreme Court took up the case of Florida v. Georgia, a dispute over water-use in the ACF system, in 2013. A year later the court appointed a special master to the case: Maine attorney Ralph Lancaster Jr., who was charged with reviewing the court-filings, hearing trial testimony and proposing a ruling to the high court. In November and December of 2016, after two years, the rare state-versus-state trial was heard by Lancaster in the coastal New England town of Portland, Maine.

“What Florida is asking for is to cap Georgia’s water use at a level that allows the Apalachicola ecosystem to survive,” says Tonsmeire.

At the same time, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is completing the first update since 1958 of its water-control manual that guides the management of waterflow in the Chattahoochee and ultimately, and most critically, at the confluence with the Flint and the Apalachicola. In early December of last year, the corps released their final environmental impact statement (EIS), which is required before changes can be made to the manual. “They gave Georgia everything they asked for,” Tonsmeire says. “The EIS made it clear that the corps intends to meet the future water-supply needs of metro Atlanta, while downstream users are left without even a fair investigation of needs. It seems premature to have this issued. Now the fate of the Apalachicola lies in the hands of the Supreme Court.”

For the last 13 years, Dan Tonsmeire and his organization have provided a voice for those who yearn for equitable water management and fear for the future of the Apalachicola River and Bay, as well as the fisheries of the eastern Gulf of Mexico. And he doesn’t intend to stop now.

“We’re at a major turning-point this year because this is our last chance to have a meaningful recovery” says Tonsmeire. “These two, almost concurrent, actions by the Supreme Court and Army Corps will determine our fate.”

An Oyster and a Way of Life in Peril

The Chattahoochee and Flint rivers merge at the Florida-Georgia border to become the Apalachicola, which flows through the center of the Florida Panhandle into Apalachicola Bay, forming one of the most ecologically diverse rivers and estuaries left in the northern hemisphere. Here the river’s fresh water mixes with salt water from the Gulf of Mexico to create the perfect environment to nurture the world famous Apalachicola oyster, much prized by food critics, including those at The New York Times. And it’s not just oysters that thrive in this seafood nursery; 90 percent of the commercially harvested species in the northeastern Gulf depend on the freshwater flows and habitats of this marine estuary.

For decades the seafood industry, and particularly the iconic Apalachicola oysters, have been an economic mainstay for the surrounding region and most directly the town of Apalachicola, a charming fishing village with about 2,000 residents, many of them third-, fourth- and fifth-generation oystermen, fishermen, and seafood-purveyors. In a good year, the Apalachicola system supports over 54,000 jobs and more than $5.6 billion in sales revenue across west Florida and the eastern Gulf of Mexico.

But the decades-long battle between Florida, Georgia and Alabama over Georgia’s unfettered use of upstream water, combined with the water-management policies of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and political gridlock in Congress, orchestrated by the Georgia delegation, have created the possibility of environmental and economic devastation.

In fact, during a drought in 2012 the oyster population in Apalachicola Bay so declined in productivity from the lack of fresh water flow that the region was officially declared a federal fishery disaster due to a “collapse,” a condition severe enough to threaten the demise of this fishery.

Florida v. Georgia

For more than 25 years, the states of Florida, Alabama and Georgia have been entangled in a legal battle over water consumption and management of the ACF system. (Alabama declined to participate in the lawsuit and is pursuing other options to get their fair share of water from the Chattahoochee, but wrote a letter supporting Florida’s claims.) Florida and Alabama have accused Georgia of unfairly depleting upstream freshwater from the Chattahoochee to provide water for the burgeoning population of greater Atlanta, and an even larger volume from the Flint for agricultural irrigation in southwest Georgia. During droughts, up to 50 percent of the flow to the Apalachicola is being used up – flows critical to sustaining the fish and wildlife in the Apalachicola floodplain and bay and the eastern Gulf of Mexico. In 2013, at the direction of Governor Rick Scott, the State of Florida sued Georgia to bring about an equitable apportionment of the waters of the ACF Basin and an adequate flow of freshwater into the Apalachicola area.

Scott declared at that time “[the] lawsuit will be targeted toward one thing – fighting for the future of the Apalachicola,” and described the suit as “a bold, historic legal action for our state” that “is our only way forward after 20 years of failed negotiations with Georgia.”

While the court-appointed special master does not have the authority to issue a final ruling in the case, the U.S. Supreme Court has historically accepted a special master’s recommendation – and even more likely when that master has been Lancaster, who has served in that role several times previously. In this instance he has repeatedly urged the 70-plus lawyers working on Florida v. Georgia to reach an agreement and end the acrimonious water dispute, but a compromise benefitting both parties has not been reached. “At an early stage of the case,” Tonsmeire reports, “Lancaster granted both Florida and Georgia confidential mediation, which has deprived everyone else, including a concerned public, from being fully aware of what is going on.”

During a February 2016 conversation with the lawyers working on the case, the curmudgeonly Lancaster commented, “When this matter is concluded – and I hope I live long enough to see it happen – one and probably both of the parties will be unhappy with the court’s order. Both states will have spent millions and, perhaps, even billions of dollars to obtain a result which neither one wants.”

Similar confidentiality undermined a five-year effort by the ACF Stakeholders – a grass-roots organization of the Apalachicola, Chattahoochee and Flint Riverkeepers, scientists, utility managers and others from Atlanta to Apalachicola – which called for water flows to be equitably managed.

But upstream water supply-interests that were parties to the stakeholders’ collaboration refused to release the science behind the plan to avoid the implications it might have on the litigation by demonstrating the potential impacts from upstream water use on the downstream ecosystem.

Tonsmeire believes the secrecy around the issue has prevented environmental advocacy organizations from informing the public about the dire situation in the ACF Basin – and, more importantly, from scrutinizing political decisions.

“We don’t know what kind of negotiations are going on between the states or behind closed doors with the governors,” he says. “Of course we’re worried.”

This situation blocks Apalachicola Riverkeeper from pursuing its principal objective, which is to secure a sustainable management plan for the Apalachicola ecosystem and survival of the livelihoods that depend on it.

“This issue comes down to the lack of sustainability of current water-management practices,” says Tonsmeire. “The ACF Basin may be on the same path to drying up as the lower Colorado River and Delta. Our area would be the first to be devastated, but water-users upstream would be the next to go; the devastation will follow, and the water war will intensify as all three states begin to lose.”

A Manual for Disaster

For years the Apalachicola River and Bay have endured a series of ups and downs at the hands of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The corps regulates upstream Lake Lanier on the Chattahoochee River, which is slated to be Atlanta’s main source of water for the future. The corps has steadily increased the amount of water it stores for Georgia’s use in Lake Lanier, as well as the West Point and George Andrews reservoirs farther south. This has altered the quantity, timing, frequency and duration of freshwater flow downstream to the Apalachicola River Basin. In 2012, Apalachicola Bay experienced the inevitable disaster that results from unlimited upstream water-use, when its ecosystem collapsed, crippling the many downstream communities that thrived from commercial and recreational fishing. But, says Tonsmeire, the corps has not even officially recognized that event, and Georgia denies any responsibility.

That breaking point was reached when periods of natural drought were exacerbated by the limited water-flow and corps policies that held water back. While Georgia benefited from increased freshwater in its reservoirs and unfettered irrigation, producing an all-time high in agricultural production, the Apalachicola received unprecedented low flows barely adequate to sustain four species of endangered mussels and the endemic Gulf sturgeon. As the situation became increasingly dire, Florida Governor Scott petitioned Congress on Sept. 6, 2012 to declare that a “commercial fishing resource disaster” had occurred in Apalachicola Bay with an emergency request for relief to the federal government.

“The State of Florida,” he stated, “has experienced an unprecedented decline in the abundance of oysters within our coastal estuaries, a direct consequence of which has been a significant loss of income to commercial oyster fishermen, oyster processors and rural coastal communities.”

Four years later, the river and bay have begun a meager recovery, but the environmental and economic consequences of the 2012 drought are still strongly felt.

“There are less than half the oystermen there used to be, and each of us used to bring in four or five times as much as we do now,” said Shannon Hartsfield, president of the Franklin County Seafood Workers Association. “The lifeline to our bay is that river.”

In early 2016, the corps proposed revisions to the policies contained in its water-control manual and environmental impact statement, but the changes it now recommends, said Tonsmeire, could create even more and prolonged drought periods for the river and bay. And this time, the waterbodies would be unlikely to recover. In addition to the corps not having recognized that the river and bay collapsed in 2012, Tonsmeire insists, they have not “considered the needs of that ecosystem.” He wonders whether “they ever even intended to help reach a sustainable, fair and mutually beneficial solution between Florida and Georgia.”

Apalachicola Riverkeeper partnered with American Rivers, Alabama Rivers Alliance and the Chattahoochee and Flint Riverkeepers to draft a petition to capture the attention of the corps and urge it to come to an effective solution of the problem. By August 2016, the petition had resulted in more than 28,000 responses sent to the corps.

“We urged the corps to go back to the drawing-board and work with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, NOAA, EPA and stakeholders to create a plan that adheres as closely as possible to the natural quantity, timing, and variability of flows to the Apalachicola and Chattahoochee Rivers,” says Shannon Lease, Apalachicola Riverkeeper’s executive director.

In addition, working with the environmental law clinics at Stanford and the University of California at Irvine, Apalachicola Riverkeeper, Florida Wildlife Federation, National Audubon, and Defenders of Wildlife submitted an amicus brief to the special master. It outlined a clear path for him to take the ecological functioning of the Apalachicola River and Bay and eastern Gulf into his water-allocation decision. Tonsmeire has also approached a number of major corporations in Georgia and asked them to consider using their influence to convince Georgia’s governor and Congressional delegation to abandon their no-compromise position and embrace a collaborative process that would provide for sustaining the entire ACF Basin.

Setting a Precedent

The Supreme Court’s decision in Florida v. Georgia will affect not just the combatant states in this water war. It will also have profound implications throughout the United States. The justices’ ruling will set a precedent for national policy and could provide clear guidance for resolving longstanding and costly disputes between states over water sharing and use. But for now, the fate of the Apalachicola River and Bay is in a painful holding pattern. And thousands of jobs and billions in sales revenues are on the line. “These decisions will affect people, communities and governments across this country battling for fairness in use, allocation and management of water across state borders,” says Tonsmeire. “The opportunity exists to guide how to share water between competing interests – like big agriculture, big development, independent fishermen and ecotourism – on a socially just and equitable basis.”

To learn more about the Apalachicola Riverkeeper and to support the organization’s work to save the Apalachicola River and Bay, go to www.apalachicolariverkeeper.org. Donations from individuals are 100% tax-deductible. Lisa Garcia is a writer and public relations executive based in Tallahassee, Florida.