Klamath River Dam Removal

By: Klamath Riverkeeper

The Klamath River’s advocates succeed on their second try with new agreement for largest-ever dam removal.

By Konrad Fisher, Klamath Riverkeeper

The largest dam-removal and salmon-restoration proposal in history now appears close to being realized thanks to a historic agreement reached in April 2016 between tribal, state and federal governments, the owner of the dams, and conservation and fishing organizations.

The agreement calls for removal of four dams by 2020 along the Klamath River, which begins in the high desert of southern Oregon and flows more than 250 miles to the northern California coast. The river would recover hundreds of miles of historic salmon habitat, and reservoirs behind the dams, which produce some of the highest concentrations of toxic algae ever recorded, would become free flowing river.

“For tribal members, this equates to food-security, health, and cultural survival,” said Leaf Hillman, director of the Karuk Tribe’s Department of Natural Resources.

This new agreement is particularly gratifying because an agreement that had been reached in 2010 – a more comprehensive one, in fact, including plans for dam-removal and large-scale restoration, plus a water-allocation settlement between fisheries and agricultural interests – expired in 2015 when Congress failed to pass implementing legislation. The 2010 “Klamath Agreements” were signed by more than 40 diverse stakeholders after a decade of protests, litigation and negotiation, and would have resolved century-old conflicts. Unfortunately, ideological opposition to dam removal by a few members of Congress triumphed over the economic interests of water users, and even the private property rights of the dams’ owner, PacifiCorp.

During the early days of 2016, however, PacifiCorp indicated that it would support dam-removal independent of the water settlement and restoration projects that were part of the 2010 Klamath Agreements, thus negating the need for new federal legislation. For three months, PacifiCorp staff participated in intense negotiations with stakeholders, including Klamath Riverkeeper.

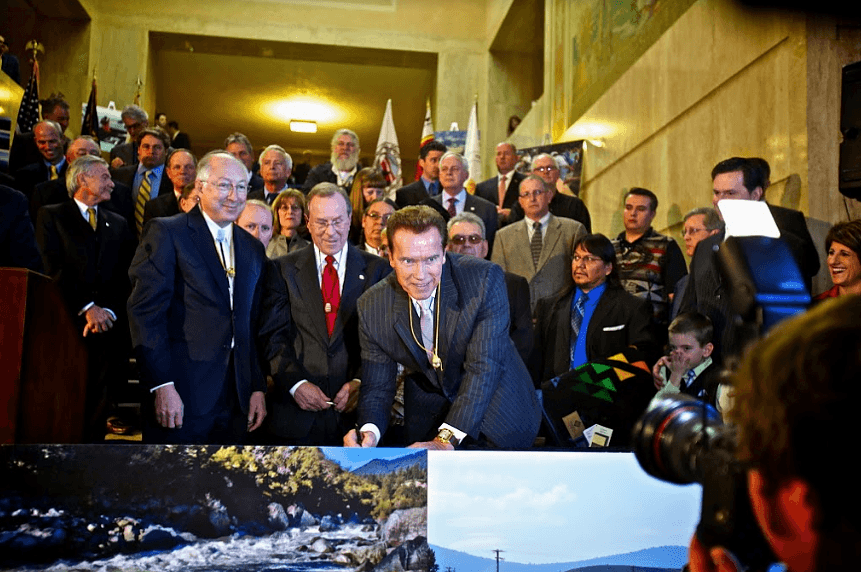

In April of 2016, PacifiCorp representatives joined leaders of the Yurok and Karuk Tribes, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, the governors of California and Oregon, and other stakeholders to sign a new agreement for dam removal by 2020. The agreement relies upon existing legal authorities and obligations of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) rather than new legislation. Stakeholders who supported the 2010 Klamath Agreements plan to negotiate a waterallocation settlement and seek restoration funds independently of the new dam-removal agreement.

How We Got Here: Fish-Kill, Toxic Algae, Protests, Litigation and Negotiation

The movement to un-dam the Klamath River coalesced in 2002 when more than 60,000 salmon died after the Bush Administration limited water-releases for fish in favor of agricultural water deliveries. The Washington Post later reported that Vice-President Dick Cheney had silenced federal scientists who warned that inadequate river-flows would kill large numbers of salmon.

Klamath Basin tribal members who were devastated by the 2002 fish-kill proceeded to lead a historic movement, joined by conservation groups and fishing interests, calling for dam-removal and improved water-management. Tribal members, along with Klamath Riverkeeper’s founders, led several large rallies before PacifiCorp’s offices in Portland, where they displayed toxic algae generated in the reservoirs behind the dams.

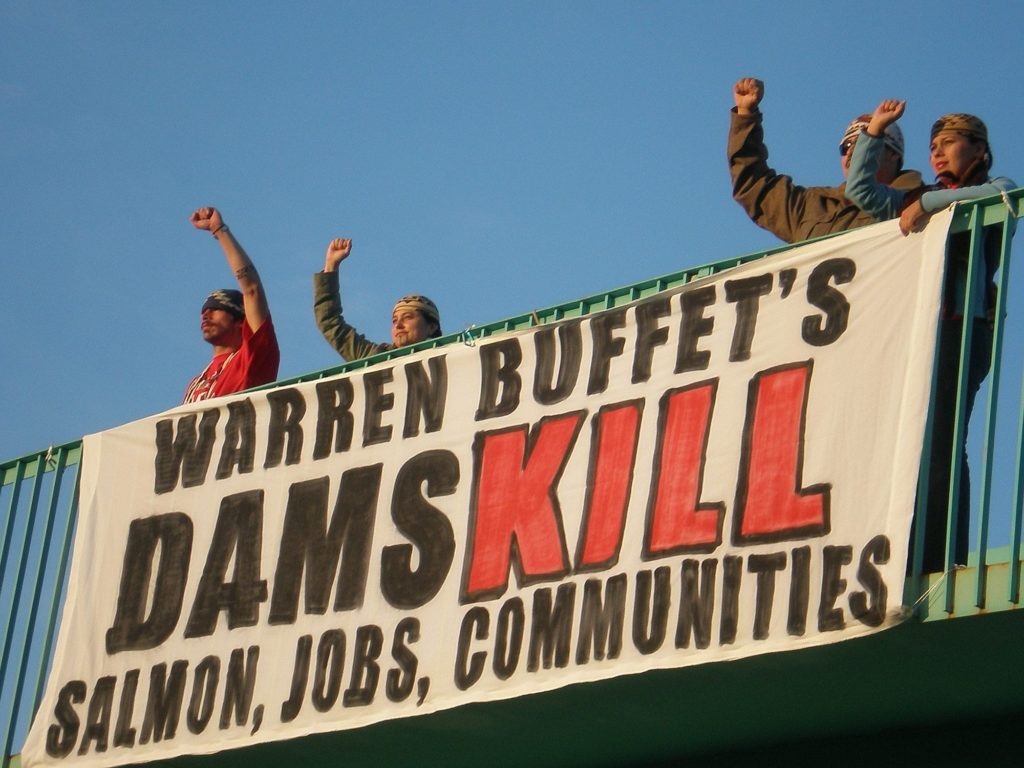

Tribal members and allies also held rallies in Scotland, where PacifiCorp’s parent company, Scottish Power, was holding a shareholders’ meeting. Scottish Power responded by selling PacifiCorp to MidAmerican Energy Company, a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway. Tribal members then traveled to Omaha, Nebraska to deliver their message directly to Berkshire Hathaway’s largest shareholder, Warren Buffett.

While the protests moved public opinion in favor of dam removal, successful legal action ensured that the dams were not relicensed without compliance with key laws. In 2006, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and NOAA Fisheries mandated fish passage for salmon as a condition of dam relicensing by FERC. PacifiCorp challenged this condition in court, but tribes and environmental and fishing groups intervened and successfully upheld the fish-passage requirement.

Meanwhile, scientists with the Karuk and Yurok Tribes collected extensive data showing that the reservoirs created by the dams generated some of the highest concentrations of toxic algae ever recorded. Armed with this information, Klamath Riverkeeper and co-plaintiffs settled litigation in 2008 which compelled the U.S. EPA to regulate toxic algae on the river. This led to the establishment of waterquality standards for toxic algae that had to be satisfied as another condition of dam relicensing.

Considering the high cost of fish passage, and lacking a viable path to meet water-quality standards, PacifiCorp acknowledged that dam-removal could be more cost-effective than dam relicensing.

The Klamath Agreements that were signed in 2010 after years of arduous negotiations included the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement, which stipulated a water-allocation settlement and multiple habitat restoration projects, and the original Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement (KHSA) for dam removal. The 2016 damremoval agreement is an amended version of the KHSA. In 2013, the Klamath Tribes of Oregon negotiated a separate water-sharing agreement with agricultural irrigators called the Upper Klamath Basin Comprehensive Agreement.

As written, these three agreements were interdependent and contingent upon federal legislation that would have provided irrigators with regulatory assurances and subsidies for water pumping, while establishing caps for surface-water deliveries and triggers for groundwater pumping curtailment. Legislation also would have funded hundreds of millions of dollars worth of habitat and water-quality restoration and ensured that the dams were removed by 2020.

Senators Wyden and Merkley of Oregon and Senators Boxer and Feinstein of California were quick to support the necessary legislation. However, despite significant benefits for agricultural interests, Congressman Greg Walden of Oregon refused to support the legislation, while Congressman Doug LaMalfa of California actively opposed it. Their intransigence caused the 2010 Klamath Agreements to expire in 2015.

PacifiCorp supported a new damremoval agreement in 2016, the amended KHSA, due to the high cost of dam relicensing relative to removal, and the availability of funds for dam-removal. To this day, an electricity ratepayer surcharge is accumulating funds that will provide $200 million for dam removal. The California and Oregon Public Utilities Commissions approved this surcharge to protect ratepayers from a higher surcharge that would have resulted from bringing the dams into compliance with water-quality and fish-passage requirements. California voters also approved a water bond in 2014 that included up to $250 million that can be used for dam-removal.

Implementing the New Deal

The new agreement contains detailed procedures to achieve dam removal by 2020. A non-profit “dam removal entity” called the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC) was formed to oversee dam removal. In September 2016, the KRRC and PacifiCorp submitted a joint application to FERC to transfer the dam operation license to the KRRC. At the same time, the KRRC submitted a dam operation “surrender application” to FERC, which must be approved for dam-removal to occur.

Former U.S. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewel urged FERC in an October 2016 letter “to approve these applications as a critical step toward resolving the significant water-related issues in the Klamath Basin.” Her letter explained that “the River and the fishery it supports are at the core of the cultural, spiritual, and economic well-being of six federally recognized Indian tribes.”

While support for dam removal is stronger than ever, some elected officials continue to oppose it. Despite ample peer-reviewed evidence to the contrary, Congressman LaMalfa and supervisors in Siskiyou County, where three of the dams are located, continue to mislead their constituents by asserting that dam removal will harm water quality and salmon populations, and burden electricity ratepayers and downriver property owners.

“We must accept that a certain number of fact-resistant elected officials will base their opinions on ideology rather than a preponderance of hard scientific evidence,” said Craig Tucker, natural-resources-policy advocate for the Karuk Tribe. “At the same time, we will continue to correct misinformation so stakeholders and the general public can make informed decisions.”

Communities that depend on a healthy Klamath River for food, jobs, recreation and cultural survival have accomplished what once seemed impossible to most outside observers. With continued dedication, the world will witness the largest dam-removal and salmon restoration project in history by 2020.

Impacts of Dam Removal

Pros:

- Reopens 420 miles of historic salmonid habitat and increases Chinook salmon populations by at least 80 percent.

- Allows salmon to reach the Klamath Tribes of Oregon for the first time since dam-construction.

- Improves commercial fishery along more than 700 miles of California and Oregon coastline, where Klamath River salmon migrate.

- Protects endangered southern resident Pacific orcas (killer whales), which depend on Chinook salmon for the majority of their diet.

- Restored fisheries will improve access to healthy traditional food-sources for Klamath Basin tribal members.

- Eliminates stagnant reservoirs that generate some of the highest concentrations of toxic algae ever recorded.

- Creates thousands of jobs from dam-removal itself, commercial fishing, and restoration of the tourism and recreational fishing industries.

- Minimizes electricity-rates because ratepayers would not incur the cost of dam removal which is less than the cost of dam relicensing.

- Reduces emission of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, from reservoirs.

- Net impacts on property values have been difficult to quantify due to lack of comparison data. Property values downriver from the dams will likely increase due to improved water quality, fisheries, and tourism. Impacts on property values on the reservoirs are unknown due to lack of applicable data – namely data about change in property values where reservoirs filled with dangerous concentrations of toxic algae are replaced with free flowing river with salmon and steelhead.

Cons:

- Temporary release of sediments into the river as reservoirs are drained.

- Eliminates a fraction of PacifiCorp’s electricity production, which can easily be replaced with new renewable electricity production capacity.